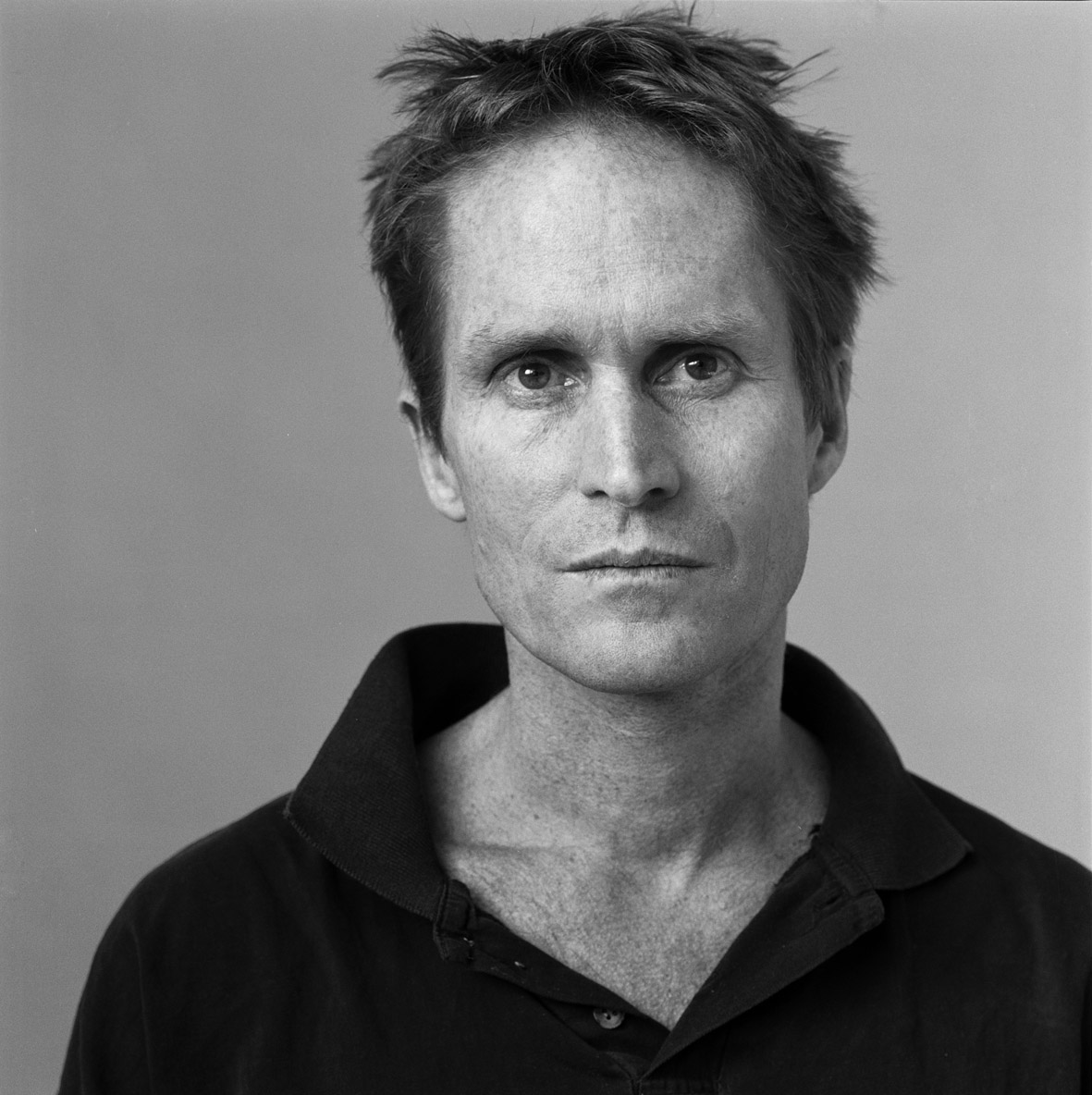

Peter Hoeg Has it on Good Authority

ABOVE: PETER HØEG. IMAGE COURTESY OF HENRIK SAXGREN

In Peter Høeg’s The Elephant Keepers’ Children (Other Press), adults are authority figures gone wild: they steal, whore, and cheat with wanton abandon. It is the teenage protagonists of the book, the children really, who save the day and search their souls dangerously while doing so. When 14-year-old Peter’s parents go missing, he and his wisely beautiful older sister go on a quest to find them. Høeg tells the story of his fictional namesake with lush candor, we see frank innocence coming of age. Both humorous and painful, Peter—both the main character and the author—tackle questions of faith and love in the search for his missing parents, deeply religious people who have lately been taking their piety to illegal levels. After arranging a date entirely by snail mail, we caught up with Høeg on the peninsula Jutland to discuss children, Tom Waits, rebels, wealth, and inner happiness.

ROYAL YOUNG: I want to talk to you about adults who can’t deal with the pressures of love and take it out on kids.

PETER HØEG: We have to make clear when I’m talking as a private person or as a writer. A problem for a writer, or at least for me is that you get asked as some kind of authority when all you really know how to do well at all is put words on paper and make a story.

YOUNG: I think the personal is always interesting.

HØEG: I don’t mind answering privately. I just think it’s an important border. I have a friend, a very wise person, and he has a one-liner about how to treat children and he says, “Love them and leave them alone.”

YOUNG: [laughs] I like that a lot.

HØEG: And what he means by that is of course not let them play on the highway. Give them love and attention, but be always clear that they, in a way, come into this world with a foundation of complete personality. Children are not growing up by being stuffed by information or character. What we have to do is basically provide them with an environment where there is love and they will take care of the rest.

YOUNG: Do you feel like that’s something you got when you were a child?

HØEG: You know, I am 54, so my early childhood was in the early ’60s in Copenhagen. I grew up in a middle-class family, and I think I had a good, protected childhood. But of course, the old kind of authority that existed, which was really the idea of the grown up world, was that rules were set by the adults and the children had to adapt. That makes you, or made me kind of a rebel. And rebel is not always the best position to be, because you are reacting against something.

YOUNG: I also think you’re setting yourself up to be squashed, right?

HØEG: Yes, it took me the first 40 years of my life to get a more harmonious relationship to society and not being on a collision course with authorities. And my personal feeling with this latest book is that there’s more kindness towards everybody. Towards all the characters.

YOUNG: I do think there’s a lot of kindness, but also a sense of humor about authority. Seeing authority as human too and equally fallible, prone to mistakes and needs and loneliness.

HØEG: Yes, I think that is very true. You can only keep another person as an enemy if you don’t see their human instincts. The moment you realize that like you, he or she is going to die and like you, he or she needs love and basic physical security, then you feel the heart of the other person.

YOUNG: How is wealth and what it buys us seductive?

HØEG: Do you know the American singer and songwriter Tom Waits?

YOUNG: Yes.

HØEG: He made, some years ago, a beautiful record called Mule Variations. And on that is a song called “The House Where Nobody Lives,” and on that he sings, “I have all of life’s treasures, and they are fine and they are good. They remind me that houses are just made of wood.” It’s a beautiful line. Everything is impermanent. As I told you, I am 54, and though I hope to have many more years, the feeling of death approaching is much different than when I was say, 30. How old are you?

YOUNG: 27.

HØEG: You better have a feeling of endless future stretching in front of you.

YOUNG: [laughs] I try. But it seems to me that the more wealth you accumulate, the sadder you would become because you’d realize that it’s never enough.

HØEG: I think it’s true. I lived some years in Africa, and that experience shaped, in many ways, my life. I experience people in general in a way happier and much more relaxed than the average Dane.

YOUNG: Why do you think that was?

HØEG: To create the modern Western technological mind, we have paid a price. We have created the industrial revolution and the welfare state and democracy, but we have paid a price, which often is not seen for what it is. Part of that price is a distance we have created from certain basic values in life that other people living a simple life might be closer to.

YOUNG: I want to talk to you about people who really enjoy power, what sort of person that is and where it gets them.

HØEG: That border between the writer and the private person, I will now try to answer as the writer of this latest book. The portrait of elephants in the book is also a portrait of people who have or possess an invisible elephant. And some of these people are pursuing power. When I have encountered those kind of people, often this quest for power is a surrogate for the real thing. They are, or we are all looking for something deeper, maybe for deeper love, but that is not easy to get, so we project it outwards on wealth or power…

YOUNG: Or fame.

HØEG: Or on conquering different things.

YOUNG: So you think there’s an internal emptiness that drive these quests?

HØEG: I think the modern world, we are looking outside for happiness and trying to change the outer world to gain inner happiness. This has to be balanced with some kind of awareness of who yourself is and that is in danger of getting lost. The knowledge of who you are, it doesn’t grow like hair and nails, there has to be some sort of conscious process to find that out.

THE ELEPHANT KEEPERS’ CHILDREN IS OUT TODAY.