rest in peace

One of Cicely Tyson’s Final Interviews, With Her Friend Phylicia Rashad

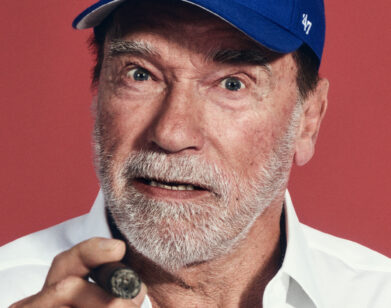

Dress and Hat by B Michael. Scarf (worn on head) and earrings Cicely’s Own.

Barack Obama put it best. “In her long and extraordinary career,” said the president, “Cicely Tyson has not only exceeded as an actor, she has shaped the course of history.” It was 2016, and Tyson was sitting in the front row in the East Room of the White House, where she was being awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. For any other performer, that honor would mark the pinnacle of a life’s work. But Tyson, who died yesterday at the age of 96, would go on to reach many. Two years later, she became the first and only Black woman to receive an honorary Oscar, a capstone to a career that began in the modeling world in the 1950s, when she was discovered by a photographer for Ebony magazine. After several small roles on television, the New York City native’s foray into acting took off in the early ’60s with the CBS series East Side/West Side, making her the first Black actor to star in a network drama. From that point, if there was a record to break, Tyson broke it.

In 1973, she became one of three Black women to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress, for her role in Sounder, in which she played the matriarch of a family of sharecroppers in Depression-era Louisiana. A year later, she became the first Black female actor to win a Primetime Emmy for her work in The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman, in which she famously played a former enslaved woman from the ages of 23 to 110. It was a performance so towering that one Emmy couldn’t do it justice, so they gave her two, with Tyson being awarded the Emmy for Actress of the Year on the very same night. Then, in 2013, she made history again as the oldest actor to win a Tony Award for her performance in the Horton Foote play The Trip to Bountiful. Along the way, Tyson has racked up just about every honor the country’s top cultural institutions have to offer, and, just to quash any remaining doubt about her longevity, tenacity, or talent, Tyson ended this decade with five consecutive Emmy nominations for her role as the outspoken Ophelia Harkness in the legal thriller How to Get Away with Murder.

If the characters Tyson has played are whole and complex, so, too, was the woman behind them. Just two days before her passing, HarperCollins published her memoir, Just As I Am, an in-depth chronicle of her extraordinary life, from her early days in Harlem as a church girl who dreamed “audacious dreams,” to her lifelong commitment to racial justice and representation. After a lifetime of telling other people’s stories, she was finally, as she explained to her friend, the actor Phylicia Rashad, ready to tell her own. —JULIANA UKIOMOGBE

———

PHYLICIA RASHAD: Here we are.

CICELY TYSON: A long-awaited moment. And I am so grateful for it, believe me.

RASHAD: May I just say, your book is beautiful. It is profound, it is poetic, it is graceful, and, just like you, it is fiery. In reading the first chapter, you asked [the civil rights activist] Barbara Jordan when she is going to write a book. She said, “When I have something to say.” When you were asked the same question, you quoted her. You have a lot to say. What helped you determine to say it now?

TYSON: I can’t count the many times over the last 10 or 15 years that someone has asked me when I was going to write a book. One day when I was in California doing How to Get Away with Murder, my manager Larry said to me, “I need to talk to you about something. You need to do your book.” I told him the Barbara Jordan story, because that’s exactly the way I feel. When I have something to say, and only then, perhaps I would consider doing a book. People think they know me, but they don’t. I barely know myself. I’m still searching for me. People are familiar with the Cicely Tyson who has all the accolades, the awards, the flowers, the tinsel on the tree. He said, “Oh, you’re talking about a Christmas tree,” and that slapped me in my face. Folks are aware of that Cicely Tyson, but rarely is anyone aware of the roots. Christmas trees come up out of the dirt and gradually begin to grow branches, and then leaves on the branches, and so on and so forth until it gets to the pinnacle and ends with the star at the top. I couldn’t get that out of my mind. I said, “Larry, you just got me started on the book,” because I couldn’t visualize anything more poignant to me than the image of me coming up out of the roots of the Lower East Side, which at that time they used to call the slums, not the ghetto, and coming straight up into another neighborhood which was a little better, and so on and so forth, until I got to where I am.

RASHAD: I find it remarkable that in this book you’ve been able to lead us to a greater understanding of your life while referencing your work, but not making the work paramount. When you began putting it together, how did it begin to take shape in terms of what you would say or what you wanted to share?

TYSON: I frankly didn’t give it a thought. I didn’t sit down and say, “I’m going to talk about this or I’m going to talk about that.” I was stimulated by the questions that the writer [Michelle Burford] asked me. I’ve been told that I have a photographic memory, and when she asked me a specific question about a situation or a person, that’s where my mind went. It amazed me that I had all of that stuff in my head. I said, “How did I carry that stuff around for so long?”

RASHAD: You not only give us a picture of your development, but you give us a framework for understanding of the world we live in today. In very vivid language, you give us America in and before your time. As you were speaking to the writer, what memories evoked the most tender feelings for you?

TYSON: That’s a tough one. There were so many, some pleasant and some unpleasant. The point is that they became very vivid when she asked the question, because suddenly there I was, either in school, at home, or at an event, and for some curious reason, the emotion was strong. It was so strong that I let whatever happened happen. I love the moments, I guess because they were so rare, when my mom and dad took the three of us out on Sunday. My father was a photographer. He loved taking pictures. We would go to the park and he would photograph us. Because of the rareness of this, due to the conflict between my mom and dad, they were very precious moments. Now that I’m a grown woman, I think about them very deeply with love and warmth and fondness. Everybody seemed so happy.

RASHAD: The first photograph in the book is a picture of you taken at your first wedding when you were 18. Why did you choose it?

TYSON: Well, I actually didn’t want to choose that photograph because I didn’t want to get married. My mother and I had a very difficult time over that. She wanted to have this big, glorious wedding for her first daughter, and I didn’t want to. It was her choice. You know how West Indians can be. I did it because she insisted.

RASHAD: That says a lot, because when we look at a photograph, we don’t always understand everything we see. Now that you’ve explained this, it says so much about you at that tender age. What was your first choice for a career?

TYSON: My first choice happened to be something that my father wanted me to do. He said, “I want to see you graduate and work in one of those tall buildings on Wall Street.” I thought, “Well that’s not so bad,” and that’s what I did. I graduated from high school and ended up working for the [American] National Red Cross, or something like that. I had a high position and was paid very well. My mother just wanted me to go to school and get a diploma. I had to leave school two months shy of graduation because I had become pregnant, and she was very disappointed in me. Two months before graduation, an enemy of my mother’s, whose son was in my graduating class, wrote a letter saying that I was married and had a child and should not be in school, and so I was called to the office and I was told I was going to be dismissed, which is what happened. I had to repeat the whole term over again at their night school, which I did, and graduated and got my diploma.

RASHAD: When did you begin to look toward what you wanted to do?

TYSON: A lot of things happened to me accidentally over the course of my life. I was working for a law firm on 5th Avenue. I was walking down the street one day, and someone tapped me on the shoulder and said, “Excuse me, miss, what agency are you with?” I looked at him rather strangely and said, “I’m sorry, I don’t understand your question.” He said, “You are a model, aren’t you?” And I said no, and he said, “Well, you should be.” I immediately found a photographer, had some photographs taken, submitted them to different agencies, and then finally I got a call, and that was the beginning of the modeling career. Later on, I walked into Our World magazine to drop off a photograph, and as I was leaving, there was a woman sitting in the outer office, and she went inside to the manager and said, “Who is that young lady that sashayed out of here just now? There’s an independent movie being shot about a Black family and she looks like just the type they’re looking for.” That was how I got started.

RASHAD: And how did you find your way to the stage, because I remember your being part of a great cast of actors for Jean Genet’s The Blacks. What was that like?

TYSON: That was very exciting, because I had never done a stage play before. We had this master of acting, Vinnette Carroll, directing it. One afternoon, I was asked to come back to meet Ms. Carroll and I was terrified. I was so frightened because she had a reputation for being very tough. She asked me about my experience, of which I had none. She gave me the script to read and told me that she was planning to do it at the YMCA in Harlem. I got the role. It was very exciting because I had never been part of a dramatic production.

RASHAD: Sometimes people don’t understand that, as actors, we have periods in which we are just so busy with great work, and that can last for a while, but then there might not be work for a while. Did you have periods like that?

TYSON: Oh, yes. There were moments when I thought that I would never work again. There were times when I would do three or four jobs in one day, little bit parts. You go in, say a line here, you go over there and say another line there, or you might be an understudy to somebody on Broadway.

RASHAD: I read in your book that you always knew which roles you wanted to play, that when you read the material you would know instantly if it was something for you to do.

TYSON: Absolutely.

RASHAD: What was it about those roles?

TYSON: When I was asked to consider an offer and I was given the script, I would read it over and over and over again. The first time I read it, I would know immediately

whether I was going to reread it or not because either my skin tingled or my stomach churned. When it churned, I knew there was no way in the world that I was going to be able to do that piece. If my skin tingled, I couldn’t sit still in the chair.

RASHAD: How did The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman come to you?

TYSON: I had been offered a film [Claudine] that was well-written and ultimately well-produced. I read it and knew that it wasn’t something I could do because it was about a Black woman who was living with some man. They were not married. She had six children, illegitimate, with different men, and I knew that was not something that I wanted to do, so I passed. I was called by the producer and the writer of the movie, who asked why I was turning it down, and I explained that it wasn’t the kind of woman I wanted to portray. The writer said, “But those ladies are out there.” I said, “Yes, I know, but there are a lot of other ladies out there. Doctors, lawyers. I want the world to know about those kinds of ladies. That’s what I want to do.” They finally decided that I was not going to do it and it went to another actress [Diahann Carroll] who did it and was nominated for an Oscar for it. They all said to me, “See, you could have had two Oscar nominations.” I said, “That’s what you would have been happy with, but not me.” Six weeks later, I got Jane Pittman. Had I been involved in doing this other movie, I would not have been available to play Jane.

RASHAD: In doing so, you touched the lives of so many people.

TYSON: Ernest Gaines [the author of The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman] gave me that. I was living in Pacific Palisades at the time, and every Sunday morning I would go to Hollywood to peruse bookstores looking for a project, and the photograph on the jacket of that book is what caught me. I did not know the woman on the jacket cover. I was taken by her face and bought the book based on that alone. I took it home, sat down on the sofa, and started reading it. I didn’t put it down until I was finished. I called everybody I knew to talk about this woman, Jane Pittman, and people were saying to me, “Oh, she’s fictitious. She’s not real.” I said, “Oh, yes she is.”

RASHAD: Oh, yes.

TYSON: I was in the process of shooting Sounder with [the director] Marty Ritt, and one day he called me and said, “Cic, have you ever heard of Ernest Gaines? He’s written a book, but I haven’t read it. He’s here and he wants me to go to lunch with him.” “I read it,” I said. “I’ll go to lunch with him.” Ernest picked me up and he took me to his home, and in his home were all these ladies, friends of his mother’s and grandmother’s, and so on and so forth. That’s when he explained to me that as a child they were always at his home and that Jane was a compilation of all of these ladies in his life.

RASHAD: You were honored with an Emmy award for that portrayal.

TYSON: Two.

RASHAD: How did it feel when you received word that you’d been nominated for an Academy Award?

TYSON: I said over and over again that one day I would be sitting in that front row. When I went to do Sounder, my dear friend [the ballet dancer] Arthur Mitchell and I were like twins. We went everywhere together. I let him know I was going to California to do a movie and he said to me, “You’re going to get a nomination.” I said, “Well, if I do, you’ll be my escort.” Sure enough, I was nominated and it was on his birthday. He flew out and we went to the Oscars together and it was glorious. There’s nothing like the first time. I think about it now and I can’t stop smiling. I’m as excited as I was when it actually happened.

RASHAD: And the accolades didn’t stop there. You received the Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama.

TYSON: Oh, wow, wow, wow. That was superior. When they called me up to tell me, “The president is going to give you the Medal of Freedom,” I said, “What?” I thought it was a joke. Finally the person said to me, “Ms. Tyson, my name is so-and-so and I am so-and-so-and-so to the president, and he has asked me to call you to tell you that he’s going to give you the Presidential Medal of Freedom. I will tell him you said yes,” and then hung up the phone. Lord Jesus, help me, please. I’m saying to myself, “Cicely Tyson, you come from 315 East 102nd Street, and here you are, sitting in a chair in front of the first Black president of the United States, receiving a Presidential Medal of Freedom. How is that possible?” His introduction of me was unbelievable. He said, “Cicely Tyson has not only exceeded as an actor, she has shaped the course of history.” Oh, Jesus. What do you do with that? And then at the end, he said, “And she’s gorgeous.”

RASHAD: [Laughs] Yes, he did.

TYSON: Oh, my dear. It was hard for me to sit in that seat. Here was this scrawny, nappy-headed little Black child from 102nd street, and the president of the United States says, “And she’s gorgeous.” Well, honey, they had me to look for after that one.

RASHAD: Your Presidential Medal of Freedom was followed by an honorary Oscar.

TYSON: Now, that was funny. This gentleman gets on the phone and says, “Good afternoon, Ms. Tyson. It gives me great pleasure to be able to tell you that yesterday 50 of our members unanimously voted for you to be the first Black woman to receive an honorary Oscar.” I never reacted to any award in that way. It was as if the whole of Niagara Falls was pouring out of my eyes. I could not restrain myself. I wept like a baby. I think about that moment a lot and have wondered why I had that kind of reaction. What I’ve realized is that when you reach a pinnacle of any kind, you probably never thought you were actually going to get there. Most of my work was done for television as opposed to the big screen. I had given up on the Oscars. And here they were, giving me something extraordinary. I really can’t put into words what that did to me.

RASHAD: In the whole of your life, what are you most proud of?

TYSON: What’s yet to come.

RASHAD: And what would you like your legacy to be?

TYSON: I think that each one of us is placed in this universe with a responsibility. I hope that so far, I have respected what god has given me enough to at least try to accomplish or achieve some of it. I don’t know if that makes any sense to you.

RASHAD: It does.

TYSON: I speak a lot to kids. I was at a junior high school one day, and a little girl got up and she said, “Ms. Tyson, now that you have made it, what are you going to do next?” I started to laugh and when I finally regained my composure, I said, “Sweetheart, let me tell you something. The day that I think that I have made it, I am finished. Do you hear me?”

———

Hair and Makeup: Armond Hambrick.

Photography Assistant: Wil Pierce.

Fashion Assistant: Reyes Cruz.