New Again: Richard Branson

In New Again, we highlight a piece from Interview’s past that resonates with the present.

Calling Richard Branson colorful for a billionaire would be an understatement. The founder of the Virgin Group, known also as a reality TV star, served passengers on a Sunday AirAsia flight dressed in drag to make good on a bet with AirAsia CEO Tony Fernandes. Branson has never been one to shrink from the public eye, but unlike other famous businessmen—such as Donald Trump—he has not seen his businesses declared bankrupt multiple times.

We sat down with Branson in 1986, when he was just 35 and ran his company out of a houseboat, to discuss the beginnings of the Virgin Group, his private island, and the time he hired a 19-year-old bartender to run Virgin’s Pub division. —Michael Hafford

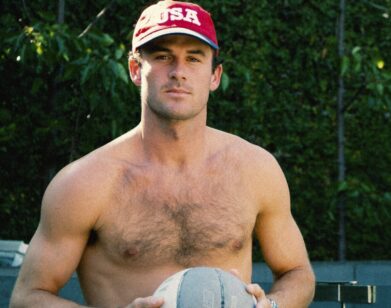

Richard Branson

By

Marilyn Achiron

Richard Branson gets what he wants—not with tantrums or pomposity, but with a sweet shyness, an unflagging politeness and a conviction that convinces. At 35, Branson is a self-made millionaire several times over. He is founder of the Virgin Group—a conglomerate of more than 100 companies that includes a record company, an airline, six recording studios, 40 retail record stores, a film company, a book-and-music-publishing unit and dozens of other smaller ventures, from cable programming to restaurants. He put his money behind the Sex Pistols and Boy George, cheap flights between London (and now Maastricht, Holland) and the United States and the 1984 film version of George Orwell’s 1984.

Branson owns an 85 percent share in the Virgin Group, which he expects will bring in $250 to $300 million in sales this year. He still conducts business from a houseboat, moored in London’s Regent’s Canal, that he bought 18 years ago for $150. Until recently, the houseboat was also home for Branson, Joan Temple, his companion of nine years, and their four-year-old daughter, Holly. Now, the three hole up in a fourteenth-century Oxfordshire manor house. The 40-acre estate is also the site of one of Branson’s recording studios.

“Until about six months ago, I never gave interviews,” he informed me across a tiny table in his hotel’s breakfast room. “I tried to keep my two lives separate. But people have a fascination with airlines.” Clad in his usual office attire—corduroys and a sweater—he looked neither entrepreneurial nor, despite his best efforts, truly comfortable.

MARILYN ACHIRON: Did you always know you wanted to be an entrepreneur?

RICHARD BRANSON: No, I had no plans to be an entrepreneur. I just wanted to be a journalist and write for a magazine. At 15, I just decided to leave school and launch a national student magazine.

ACHIRON: That was Student.

BRANSON: Right. And in order to run a national student magazine, I soon realized that the editing is one thing, but you’ve got to sell the advertising and worry about the distribution and the printers. You end up having to become a businessman just to get the magazine out. So it wasn’t from a desire to be a businessman. Since then, I’ve gone into projects because I’m interested in them rather than because it would make us the most money. Often, because of that, the projects do much better, because all of us are willing to work long hours at it.

ACHIRON: I know you’re involved in a great many ventures—the airline, records, video, restaurants. I hear you’re going to start a humor magazine. You can’t possibly know all there is to know about all these different ventures. Do you start these things up yourself or do you have consultants—

BRANSON: No, I completely immerse myself in setting up a new venture and then find a chief executive to run it. Then, having delegated, I am free to take a sabbatical for three months and the rest of the Group will run, to an extent, without me, enabling me to launch a new venture and to spend a lot of time and effort on it. We’ve been able, over the years, to build up really good people. For instance, Simon Draper, who runs the record label, joined when he was 19 and I was 17. The same goes from company to company. One of the reasons we manage to keep people is because I’m interested in moving the company into new areas, generally the entertainment business. That means that someone who’s working for records one day can move on to work for book publishing the next or magazines next or films or whatever.

ACHIRON: Why did you leave school at age 15?

BRANSON: I used to spend all my time playing sports and no time in the classroom. When I was 14, I tore the ligaments in my knee and couldn’t play sports anymore. So, having not studied for 13 years, I realized that it was going to be an uphill struggle to become an academic. I was also fed up with school—fed up with having to spend an hour a day in church and an hour for learning Latin. The whole day seemed designed just to take up time. It was the late ’60s, and I decided that a national student magazine, run by students who wanted to put the world right, should be launched. It was also something for me to do. I didn’t have any money. I told my parents I was going to quit. They were very good about it. They said if it works out, fine; if it doesn’t, you can always go back to school.

ACHIRON: How did you start the record company? Where did the money come from?

BRANSON: In the last issue of Student, I took an ad saying “Virgin Records—ten to 60 percent off any record, any label.” Nobody discounted records before I did and nobody specialized in selling rock records. You’d always have Andy Williams stacked alongside Frank Zappa. Since we were selling by mail the kinds of records we were interested in, the flavor of the ads appealed to our own age group. We had a lot of replies. We went to record companies to buy the records and they refused to sell them to us because they didn’t want the discounting of records to come into England. So we started buying them from a little shop in the East End of London. Then there was a mail strike. I went down to Oxford Street one day, looking for a little to sell our records from. Finally, I went into a shoe shop, went up the stairs and there was an empty floor. I asked the manager if he’d like to let us have it for a few months. He said fine. Little did he know what was going to hit him. We opened up about two weeks later. The shoe shop was just solid with people waiting to go upstairs. There was a queue all the way down, around the corner to the Tottenham Court Road tube station. For about three years, all the other retailers got together and said they wouldn’t discount. So we had three wonderful years when we were in shops above shoe shops and in basements—usually on the outskirts of towns, but people were willing to come to us. The shops reflected the period: pillows on the floor, headphones, which nobody had in shops before, and lots of people smoking. But still the record companies wouldn’t supply us. So this little shop in the East End of Longon had a turnover of about ten million pounds. The local rep was driving around in a Rolls-Royce.

ACHIRON: I’ve heard that you’ve got some plans for an island of your own. About the plans—and also about how and when you found this island….

BRANSON: Well, I was in New York about eight years ago and somebody asked me if I had named Virgin Records after the Virgin Islands. I hadn’t heard anything about the Virgin Islands. It was on a Friday night and I pulled out a map of the islands. I didn’t have the money to buy an island, but I thought it would be a fun excuse to go down to the Virgin Islands. I rang a friend and asked if he knew anybody who specialized in selling islands in the Caribbean. He told me of somebody in Newcastle-on-Tyne, which is our coal-mining district up north. I rang him and he arranged for me to be met on the Virgin Islands. I was rushed through customs because I was coming to buy an island. A car was laid on and I was rushed off to a lovely house. A helicopter was laid on the next day and off we went to look at the islands. I thought, “This is an interested way to travel: Just pretend you want to buy an island.”

There was this island called Necker Island which had four gorgeous beaches, a lovely lake in the middle and a beautiful hill. It was rather special. They were asking some astronomical price for it. I offered one-twentieth of what they were asking and I was hurried off the Virgin Islands. Anyway, about two or three months later, I got a call saying, “If you up the price just slightly, you’ve got a deal.”

ACHIRON: Care to disclose how much?

BRANSON: About $300,000. Since then, it’s cost a fortune. We’ve spent five years building this beautiful house with fourteen bedrooms on top of the hill. There are swimming pools and tennis courts. We were going to put a recording studio into it, but I think we’ll keep it a private island.

ACHIRON: Just for your relaxation?

BRANSON: I’d only have time to get there two days a year. I’ve only actually seen it five days since I bought it seven years ago. These things always sound wonderful, but finding the time to enjoy them is another matter. We will use it privately for Virgin people and I think we’ll also rent the island out if a few people just want to get away.

ACHIRON: Do you find yourself being inundated with ideas from people who know you can finance these kinds of things?

BRANSON: Yes. I suppose we must get about 10 projects presented to us a week. We set up a new venture maybe once a month. One or two months ago I was in a pub and the barman at the other side of the counter was expounding on what would make a wonderful pub. So I told him he no longer needed be barman at the pub; he could come and set up the Pub division for us. And now, a couple of months later, he’s launched a pub which is packed to the brim with people.

ACHIRON: For Virgin?

BRANSON: Yeah. Virgin Pubs. Got a great atmosphere. This guy’s only 19 years old.

ACHIRON: Your friend, Simon Draper, once said that you were just interested in the chase, that once you finally win what you’re chasing, you lose interest. Is that true?

BRANSON: I think that’s a fair comment. My girlfriend sometimes thinks it’s true, but we’ve been together for nine years.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE APRIL 1986 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.