“We Were Smothered and Beaten and Left in the Dark.” Mikel Jollett Tells Finneas O’Connell About the Cult that Nearly Killed Him

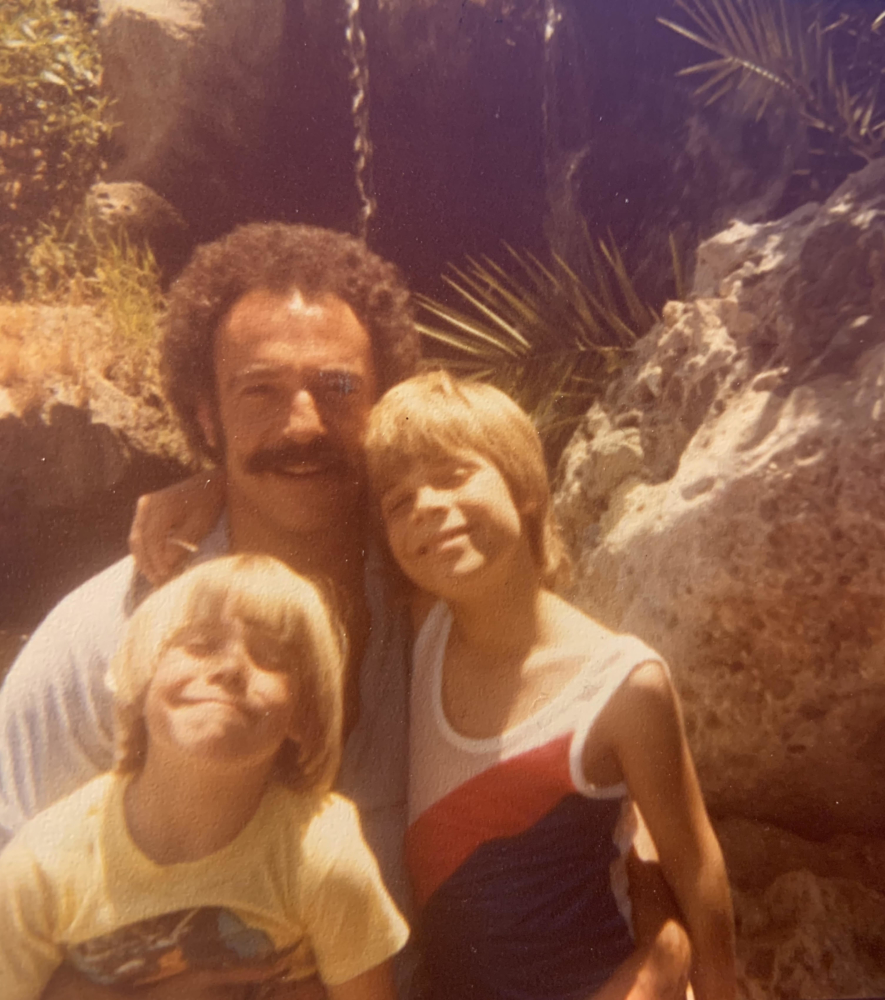

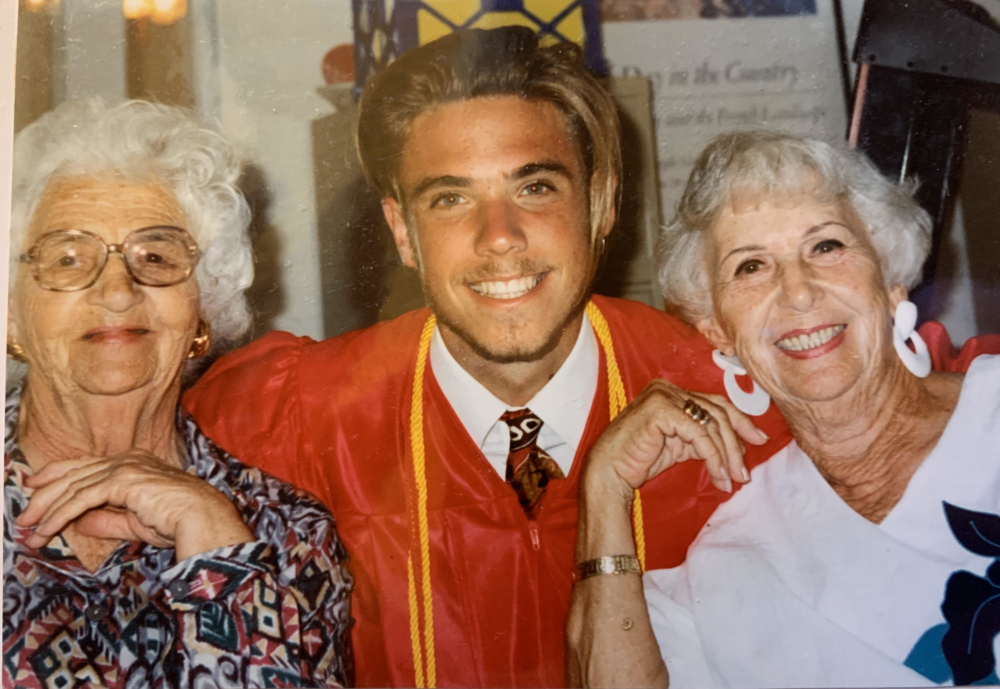

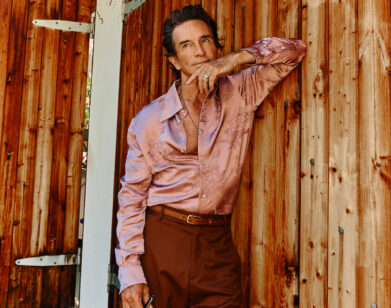

“No one ever tells us we escaped from a cult,” Mikel Jollett writes in his gut-wrenching and exhilarating new memoir Hollywood Park (Celadon). That’s not because Jollett didn’t escape with his older brother and mother from a cult—they did. It’s because no one called it a “cult.” They preferred the word “commune,” and the commune in question, which serves as the nightmare phantasmagoria of Jollett’s earliest memories, is the Church of Synanon, an experimental California collective that started out with good intentions and ended up abusing and manipulating its adherents. Today, Jollett is famous for being the frontman of the L.A. band The Airborne Toxic Event. But the 45-year-old musician also proves to be a nuanced writer, building a vivid and heartbreaking story of a childhood ringed in poverty, drug abuse, rage, and missing parents, where the world around him spins with chaos even after their escape from Synanon. Jollett has been working on his memoir for the past few years, and the release of the book coincides with his band’s sixth album, a companion piece of sorts, also called Hollywood Park. The musician Finneas O’Connell came of age listening to The Airborne Toxic Event, and got to talk with his fellow rock-star Angeleno about sibling bonds, killing rabbits, making music for the right reasons, and why childhood is a place you can never truly leave behind.—CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

———

FINNEAS O’CONNELL: How are you doing these days?

MIKEL JOLLETT: We’re doing okay today. There are ups and downs, good days and bad, like everyone else. How about you?

O’CONNELL: Doing okay. We’ve had some incidents the last couple of days with some fans showing up at my house and at my sister’s house looking—

JOLLETT: Oh, I hate that.

O’CONNELL: Not to be too conservative, but I’m building a wall in front of my house right now.

JOLLETT: And Mexico is going to pay for it.

O’CONNELL: My wall has more justification than the other wall.

JOLLETT: Your wall actually has a purpose.

O’CONNELL: [Laughs] Well, it’s great to get to talk to you. I’m assuming you’ve gathered from my tweets that I’ve loved your band for a long time, and you’ve had tons of influence on the music that I’ve made.

JOLLETT: Dude, thank you. I’m deeply honored to hear that. I’m a big admirer of yours as well.

O’CONNELL: I was given your book by a mutual friend. I’d known that you were writing it and that you’d made an album with the same name. But I finally got a chance to read it when the quarantine happened. I’ve been reading, like, 75 pages per day. The book gets more and more optimistic as it goes on.

JOLLETT: Yeah. There’s a lot of reason for pessimism at the start.

O’CONNELL: It is like the heaviest first hundred pages of any book I’ve ever read, and it’s just your childhood, which is insane.

JOLLETT: I wanted the book to start with this sense of disorientation, almost like you don’t know where you are for the first ten pages so you’re thinking, “What’s going on?” I was really interested in this idea of buried history and slowly discovering the truth after being fed a false narrative about what you are. Because that’s what it means to live in the mind of a child. Three-quarters of the book is written from the perspective of a child. So there are moments of confusion where the narrator says stuff that is patently just not true because that’s what the adults in the commune have been telling him. That’s what I really wanted to capture more than anything else—the really big, vexed, mysterious, and sometimes violent world of a child, particularly an orphan’s imagination.

O’CONNELL: I had a very positive, wonderful, happy upbringing, and still, for several reasons, I really didn’t enjoy being a child very much. I felt that I had no control over my life and everything seemed scarier and larger than life. Obviously, you were going through many more traumatic experiences than most people your age were going through. And it’s exacerbated by the fact that you’re fed information by older people who are discounting your opinion.

JOLLETT: Yeah, there are definitely some other-ing aspects to my story. My dad was in prison when I was born in a cult. I was in an orphanage. These all sound really scary and big, but when you get down to it, that wasn’t what was hard about it. What was hard was that I was lonely and confused and I wasn’t having my needs met. In that way, the story is no different from a lot of childhoods if your parents aren’t interested or you don’t feel safe. The hard part was just having no one to talk to in the middle of the night.

O’CONNELL: A book about a child born in a cult is a unique story, and yet you do universalize it in the sense that it’s easy to put myself in your shoes.

JOLLETT: I think a memoir is often one of two things. It’s either autobiography, with a list of dates and jobs and awards and all that crap that’s really boring. Or it’s emotional disaster porn, where this happened and then this happened, all these horrible things, and after a while you’ve just got to look away, like, “God, make it stop.” But I wanted to probe other questions, like what are the lies we are told and when do we start understanding them to be lies? I always think of [Frank McCourt’s] Angela’s Ashes and the protagonist who’s obsessed with this Irish folk hero named Cuchulain. The reason that he’s obsessed with this larger-than-life folk-hero warrior dude is because he’s 6 years old and he lives on potatoes and soup and he’s got no shoes, and his house is full of fleas. There’s a sewer running down the middle of the street. It’s alive in his imagination. I, too, wanted to write about what I imagined was happening as well as what was actually happening. I felt like giving those two things equal weight would be a way to occupy the perspective of a child effectively.

O’CONNELL: Your characters are really three-dimensional. There’s so much empathy. And the more you learn about your parentage from your birth mom, you’re just like, “Oh my god, this is so unstable and crazy that he’s having to deal with all of this stuff.”

JOLLETT: Someone said that when writing a memoir, it’s important to write about troubled relationships from a place of great love because otherwise you just want to write them off. Part of you is just angry that these things happened, and you’re mad about it. But if you write from that perspective, it feels like an agenda, and I think it gives off the whiff of bullshit to the reader. I think it’s best to write without an agenda. And it’s best to write about difficult relationships, trying to see their struggles, trying to see what they went through. Let’s say they’re a starving family, and a man comes home, and he’s got a bag of oranges. And he eats all of the oranges. And that’s all you know. He doesn’t share the oranges. It’s like, “Oh, this guy’s an asshole.” But if you know one more detail of the story, and the detail is he has scurvy, then if he doesn’t eat the oranges he’s going to die, and then he can’t support his family. So the idea is to always look for the scurvy. What’s the piece of information that’s going to help explain why the people are acting the way that they’re acting? In the case of my mom, I tried to do that a lot. I think she honestly tried to outrun her demons, and I don’t think she ever intended to hurt us. I think it just kind of worked out that way.

O’CONNELL: I’m not an author, but as a songwriter, I’m afforded this kind of luxurious ambiguity in songs of being able to confess the secrets of my relationships with people and face basically no consequences, or ask for no approval or permission. I don’t know if that’s your experience, but it’s certainly been mine. If I have experienced something in my life, it’s probably going to be written about, and I don’t particularly care if the person I’m writing about wants to be written about.

JOLLETT: Why would you? You’ve got to be a pure artist at that point. At that moment, you’re just an artist. You’re nothing else. You’re not a human that has relationships in the world. You’re a person trying to get the story or the song right. I’m totally with you on that.

O’CONNELL: But with a memoir, when you write about your mom, everyone knows who you’re writing about. Did you warn people? Or inform them? Did you have to ask permission or did you need help remembering certain situations?

JOLLETT: That’s a good question because it’s rocky. I will say this: I just wrote it. Everyone knew I was writing it. Friends and family knew. But I spent about two and a half years writing it without showing it to another soul except for my wife. I had this huge Microsoft Word document that was the book, and it was like building the Watts Towers in your basement. It’s just this huge, intricate, ornate, detailed thing. And I was terrified to give it to my brother because I don’t think he knew I was going to write about his heroin addiction and all of this stuff with his son. I was terrified of what he thought because it mattered to me. We’d experienced the same thing and we had always said, “Hey, you’re the only other person on this planet who understands what we went through.” And he was also the one who could call bullshit. So, he read it, and he was just the opposite of petty. He was warm, supportive, and generous. He said, “I cried, and I love it,” and, “I know I don’t always look good. But you know what? Neither do you. This is what happened. This is the truth.” He was just so large-hearted about it all. I was so relieved.

O’CONNELL: I think that’s the mark of true sibling shit. Their opinion weighs three or four times heavier than that of a parent or friend. It’s so massive, maybe because they were your first peer.

JOLLETT: Writing the book helped me to understand my brother so much better because I could look at our relationship and be objective about it. His stance throughout our childhood was that all adults are full of shit. He was in an orphanage until he was six-and-a-half, and no one talked to him about it. We went to Oregon, and we were on food stamps, and we were wearing clothes from the Goodwill. And while I never really had a problem with the fact that we were poor, my brother hated it. I was like, “We have soup for dinner, so what? Okay.” My brother resented the shit out of it, and I think a lot of tension we had as kids was that he saw things clearly in ways that I didn’t. He was really angry with the adults. I think he saw me as working for the other team. He saw me as a spy in enemy territory. And I think he wondered why I didn’t just come to his side and decide that they were all full of shit.

O’CONNELL: I’ve been a listener of yours since your first album, and it’s really fun thinking about how this memoir contextualized the lyrics in all of your albums and now this new one, Hollywood Park. Did you know the book and the album were going to come out simultaneously?

JOLLETT: Yeah, about halfway through writing it, I did. I don’t know if you’ve gone through this process, but when I wrote my first record, it was just kind of straight poetry. I wrote it alone in a tiny apartment in Los Feliz. And what happens is, you put it out and go on a tour and if it does well there are always assholes at the major labels in the music industry, dinosaurs, who will be like, “Let me tell you something, kid. You’ve got to write a fucking hit. Wang Chung 1982, ‘Everybody Wang Chung Tonight,’ that was a fucking hit. Write me one of those Wang Chung hits.” They think they’re smarter than you and know more than you. And you’re just like, “I know enough to write this music that you loved.” They’re so excited to sign you and then when they do, it’s like, “Well, you’ve got to make it sound more like bullshit.” That’s really what they’re saying. And you’re like, “I don’t want to write bullshit. That’s the whole reason I’m a musician.”

O’CONNELL: My favorite song off the new album is “I Don’t Want to Be Here Anymore.” I just love that song.

JOLLETT: That song is about the moment we left Synanon, and we were living on the run. We found ourselves first in Oakland, and we were just going to the food bank for food. And we were going to the church for that government cheese they used to have, which was basically a five-pound block of Velveeta. It was terrible except for the grilled cheese and noodles. We were just dirt poor. And then the goons from Synanon were sent after us, so we weren’t allowed to leave our room, and we could hear the other kids out in the street. The line was always, “The bad men are coming, the bad men are coming.” One of my earliest memories is being told that I can’t go outside because the bad men are going to come take me away.

O’CONNEEL: And they did show up.

JOLLETT: Lo and behold, they did. It was one of the few days we were allowed out, probably because my brother had just worn my mom down with the constant calling of bullshit because that was his line on the whole world. And she let us out. He was playing with the kids across the street, and I was on the porch. And these guys showed up. And you knew they were from Synanon because they had shaved heads, and you could see they had these flesh-colored, bank robber–type masks on. They were carrying clubs. Then Phil, our roommate, got out of his car—he had this old VW bus like a good hippie—and they just started beating him. He fell over, and he started screaming, and I remember our eyes met because I was frozen. I was only 5. I didn’t know what to think of any of this. And so I hid on the porch. And then one of the men asked where Tony and I were. Of course, Tony was across the street, but nobody knew who we were because we weren’t allowed outside. None of them knew our names. Then a neighbor lady came out and started screaming that the police were going to come.

So they took off, and the ambulance came, and we started screaming and crying, and Phil got taken to the hospital, and he was in a coma for a month. At that point, we were on the run. We went dark and we didn’t tell a soul where we were. First, we went to San Jose to my grandparents’ house to hide. And then, just like that at 5 a.m. in the old Vega with wooden doors on the sides, we drove to Salem, Oregon, without telling a soul. Nobody knew that my mom had found a job up there at the mental hospital. We got a place in between a graveyard and the state mental institution, the glamorous part of town. So that song was just about that road trip, and about that time, and about just how much anger we had. Nobody asked us how we felt. We were just sort of treated as accessories. That’s the anger, the righteous anger, of wronged children.

O’CONNELL: I first listened to the album on a hike up into Griffith Park, and I thought it was great. After I read the whole book, I went back and listened to the record again and enjoyed it in a whole different way.

JOLLETT: I was trying to make a soundtrack, and I had in mind these great rock-and-roll concept records, which used to be more common. Frank Ocean has done it in the modern world. But Pink Floyd’s The Wall and Springsteen’s Born to Run, these records were just big old rock-and-roll records that were tied to a narrative and a theme, and you could listen to the record and feel like you were getting a glimpse into someone’s psyche, someone’s childhood, maybe the historical events that led to some of what accounted for that childhood. In the case of Roger Waters, it had to do with World War II and his dad being killed in the war. For me, it was Synanon, and my dad’s time in prison, and my dad’s time as an addict, and then the death of my father later in my life. It felt like I just wanted to do this one thing right. I’ve never worked so hard on anything, and I’ve been at this for a while. I felt like you get one chance to really do something great in your life, and I wanted it to be exactly right, every page, every song, every note.

O’CONNELL: For some reason, I have very vivid memories of the first times I heard your band’s music. The first time I ever heard Airborne Toxic Event, my friend was turning 11 or something. And he had a paintball birthday party where him and me and two of our other friends went out to these paintball courses and I got obliterated. I don’t think I got one hit.

JOLLETT: Paintball is low-key hard. You think it should be easy, but people are vicious.

O’CONNELL: Yeah. And I remember on the way back, his mom had the radio on. I remember that “Rape Me” by Nirvana came on, and as an 11-year-old kid, those lyrics were very provocative and intimidating. And then [The Airborne Toxic Event’s] “Sometime Around Midnight” came on, and there’s that line about how “you can see her lying naked in your arms” and I was shook up by that. It loomed so large in my mind. I liked the song but was intimidated by it like all great art when you’re a kid. Right? Where you listen to a song and you’re like, “Whoa, I don’t know if my family should know I’m listening to this.” And then I remember being 13 and lying in bed at like one in the morning, watching your bombastic session video for “Changing.” You’ve got the dudes dancing. And I remember just being like, “This is unbelievably fresh. I can’t even believe it.” And then I watched all of them in the same night. I remember downloading the album immediately, and it just became a part of the collection of music that meant a lot to me over the course of my whole adolescence. My whole family has heard it because I play it all the time.

JOLLETT: Oh, those poor people.

O’CONNELL: I’m embarrassed to say that “The Graveyard Near the House” has been re-appropriated for, like, three girlfriends of mine.

JOLLETT: That’s why we’re here for each other, man. That’s what we do. You know, that reminds me of a guy named Lewis Hyde who wrote a really powerful book called The Gift in the 1980s. His big idea is that art itself if a gift and you have to exist in the economy of gifts and gift-giving. So you experience a song or a movie as a gift that comes into your life. And one of the things that he says that I’ve had written on my wall for a long time is, “We are lightened when our gifts rise from pools we can’t fathom.” The idea being that the best stuff is always the stuff that comes alive and you don’t have any idea where it comes from.

O’CONNELL: The beautiful thing about art is that it’s all opinion, right? It’s all just like, “I made this thing.” And someone goes, “That connects with me.” And someone else goes, “Well, this other thing connects with me, and that doesn’t.” There are enough people in the world that if you make something that connects with some people, you can have a really successful career making stuff that connects with some people. And that’s such a different metric than, say, awards or sales figures. I can’t believe people care so much about whether their album charts. I didn’t know that people got into this to be the most successful toothpaste brand. I just thought they wanted to make songs.

JOLLETT: Some of my favorite artists, they’re not recognized by awards. And those are records that I’ve listened to hundreds of times because they spoke to me so deeply. I have this good friend from college who’s an investment banker. If you want to make money, it’s a really efficient way to do it. If you want to be an artist, then make some fucking art that means something to you, that speaks to your world and makes your world feel bigger and scares you a little bit.

O’CONNELL: To me, if you’re looking for a metric of achievement as an artist, it’s a venue that you’ve always wanted to sell out. That’s a great achievement. Like, I wrote songs I actually believed in and got to play them at this venue I always dreamed of playing in.

JOLLETT: How are you so wise for your years, man? How do you know these things at 23? I didn’t know those things when I was your age. But that’s exactly right!

O’CONNELL: Well, thanks. I wasn’t having to club rabbits over the head my whole childhood like you did. When I read that I was like, “I would be so fucked if I had to kill rabbits all the time.” That’s the opposite of Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000-hour theory of genius. “Mikel wrote ‘Sometime Around Midnight,’ and that propelled his band’s first album to mainstream success. How did he get there? Well, he killed many rabbits a week every week for X amount of years as a child.”

JOLLETT: Oh? You’d like to be a songwriter? How many rabbits have you killed?

O’CONNELL: Is there anything you want people to take away from reading your story?

JOLLETT: I think I wrote the book out of a desire to be heard. It’s like the songs I’ve written that I’m most proud of. They come from a place that cries out to be acknowledged. I want this to be a thing that lives in the world because then it doesn’t just have to live in me. This book is the story that lived inside me for so long.

O’CONNELL: I also think that a lot of people are going to read this book and have a light shined on their fucked-up childhoods. Never underestimate how many people have had turbulent upbringings who might not have any tells. It seems like for every five people I talk to, two or three of them are like, “Well, you know, my parents were totally addicted to drugs.”

JOLLETT: And you’re like, “No, I didn’t know that at all.” I do think there’s a mundane quality to my story despite all of the sexy bullet points of my childhood. There’s still just a longing for empathy, a longing to be seen, a longing to commune with people. You long for love, you long for a place for imagination and creativity. And really, we were denied those things. I come back to the image of the bunnies because the bunnies are living creatures that we raised and slaughtered and ate. But they’re also symbols. They’re symbols of the extinguished children that we were. We were smothered and beaten and left in the dark.