tea

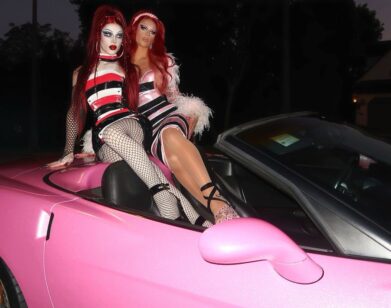

Michelle Visage on Drag Race, Clubbing, and the Importance of Queer History

As a fixture of the RuPaul’s Drag Race judges table for more than a decade, Michelle Visage has seen enough bad leotards and questionable wig decisions to last a lifetime. Her knowledge and appreciation for the history of queer culture, though, didn’t appear out of thin air. As a Jersey girl who moved to New York in the ‘80s, she became immersed in the city’s ballroom scene, voguing under the watchful eye of legends like Willi Ninja and Cesar Valentino. Later, she performed in the pop/R&B girl group Seduction, and, eventually, found a spot on the most illustrious panel in drag history.

Visage, who now has a queer daughter herself, manages to exist and thrive in two separate timelines: as a woman who preaches the importance of LGBTQIA+ history, while also part of a television franchise that is pushing the community to new heights. We caught up with her in the midst of the 13th season of Drag Race to chat about the state of drag today, and the importance of remembering its roots.

———

DANIEL TRAINOR: Hi Michelle!

MICHELLE VISAGE: Hi Daniel and Sam! How are you?

SAM STONE: We’re doing so well, thank you so much for being here with us!

VISAGE: “Hit me with your best shot.” —Pat Benatar.

STONE: Dan and I do a lot of interviews with drag queens and we always get to talk about drag as it is today. We don’t often get somebody with your perspective. You’ve been in the scene since the late ’80s—the queer scene, the ball scene, the voguing scene. We’d love to hear your perspective about that time in your life, how you got involved, and how different today’s scene is.

VISAGE: You know, if you look at my backstory, it’s not something that was in my trajectory, being a cis-gendered, heteronormative, dick-hungry girl from New Jersey. I moved to New York City when I was 17. I moved there in June and I realized really quickly that I didn’t have my crew, my girlfriends that I had in New Jersey. When I say my crew, it was one person.

TRAINOR: That’s a crew!

VISAGE: Full disclosure, I graduated high school in ‘86. I never lie about my age. Seduction was formed in ‘89. So I moved to New York, and teen night clubs were all the rage in the tri-state area. Because I wasn’t popular in high school and the boys didn’t really like me, I would go to all these different clubs around New Jersey because they had different trade, honey. They had boys who didn’t know who I was. I just never fit in in my high school. From an early age, I was very obsessed with the different. The punk rock scene in the U.K. always tickled me. I think it was the tenacity and the ballsiness of these men and women that would go out looking like that. I was like, “I want to stand out like that, I want to be different like that.” I’m sure part of it was for attention, but part of it was just to find my footing in the world of individuality because I wasn’t accepted and I was bullied and I was picked on. The boys never liked me. Girls and I got to be okay once they noticed how funny I was. To the naked eye, I could look like I was popular. I promise you I wasn’t. I made people laugh, but I couldn’t get laid at my school. So, I would go to these teen clubs almost every night. It was where I felt popular. It was where I felt pretty. It was where I felt free.

TRAINOR: Wow.

VISAGE: I’d be in the middle of the dance circles always. I was like the hot little blonde girl, you know what I mean?

TRAINOR: Sure.

VISAGE: When I moved to New York City, I knew nobody. I was really ‘80s-depressed, because they didn’t look at depression the same way back then. My mother didn’t really know how to help because they were 45 minutes away when I was in Manhattan. I had made some friends in school, but they weren’t club junkies. My mother said to me, “Well, you need to start going to nightclubs to get your juice back.” But I didn’t come from a rich family, so I was already living in New York City and going to school in New York City and my parents were paying for that. My mom told me I needed to go out, but I was like “I’m scared, you put the fucking fear of God in me to not take the subway!” I didn’t have the money to take a cab. So I ended up asking my best friend that I made at school to come out with me to a nightclub. My mom told me I needed to go, and I was like, “Mom, I am 17…how am I going to get into a nightclub?” They were all 21 and over. They didn’t have teen clubs in Manhattan. So, like a week goes by and I get this package from my mother. It was a fake ID with a letter that said, “Now you have no excuses.”

TRAINOR: Wow!

VISAGE: By the way, let me just preface this by saying I never drank. I never drank, I never did drugs. So, she was not worried about me becoming a teenage alcoholic. She sent me that and, to back it up if the bouncers didn’t believe my ID, in another separate envelope, she had a notarized fake birth certificate.

TRAINOR: Oh my god.

VISAGE: My mother went there.

STONE: She went for forgery, darling!

VISAGE: Oh honey, all the way. Like, hello! That probably could have ended her up with some sort of prison term. But that’s what a good Jewish mother does. So, I go to this club called The Underground. After The Underground it became the Palace de Beaute. The Underground was the place where all the kids would go and I was a kid. I went, but I didn’t know anything about gay lifestyle, gay anything. I knew what gay was, but growing up in South Plainfield, New Jersey, I knew a few bi people, wink wink.

TRAINOR: [Laughs.] Yeah.

VISAGE: So, I go to The Underground with my friend and the guy is like “Oh okay, but you have cute little abs and you’re wearing a bra, so you can come in.” We go downstairs and my girlfriend who was with me, her name was Aria, was in the bathroom. I was on my own. I walk downstairs because I’m excited to see what New York City nightlife is all about. This Jersey girl was ready to spread her wings! I walk downstairs and the most beautiful brown-skinned boy I’ve ever seen walked up to me, and I was like “Oh my god, I am going to get lucky immediately.” He opens his mouth and he’s like “Girl.” Right away, I was like, “Uh oh, this might be going a different way.” He’s like “Girl, Miss Thing, you have the most beautiful face I have ever seen,” and I was looking around like, “Is he talking to me?” The only person who ever told me that was my mother. He was like, “Miss Thing, come with me,” so he brings me downstairs. Meanwhile, I don’t know where my roommate is. You walk through the dance floor and, to the left, there’s this dark room in the back. I was like, “I’m either going to get killed or this is going to be the best night of my life.” I go back into this dark room and it was literally when Dorothy clicked her heels. I had found my home. I had found my family. It was 30 or 40 of the freakiest-looking misfits doing this weird dance I had never seen before. They were like, “Hey girl, come out here and join us!” I was like “Okay!” No questions asked. I was not too fat, too short, too white, anything. I was beautiful to them. They invited me in and that’s how it all began. Willi Ninja was there. It all began that night at The Underground. That’s when I was welcomed into this group and the House of Magnifique was formed. I learned what a House was, I learned about the Harlem ballroom scene. I was fully immersed. What’s changed, sadly, boys, is that I felt complete acceptance all the time. I always felt loved and accepted. Then came this shaming, cancel culture, “you can’t sit with us” bullshit within our community. Even if you feel like I don’t belong in the LGBTQIA+ community, I’m seeing more and more people saying “Ew, you’re this, you’re that.” Whatever terminology you want to use. “You can’t sit with us, you’re not fierce.” That stuff is gross. That didn’t exist when I was first introduced to the community. I swear to you, Houses would battle each other and there might be shade and there might be conflict, but it was never unresolved. It was always love.

TRAINOR: It does seem like things were undeniably more exciting and edgy, and maybe even a little bit more dangerous back then. I’m wondering if you can look back and point to a moment when that culture of inspiration and support started to shift?

VISAGE: I don’t have the answer, but if I were to guess, I think it probably started at the same time that social media reared its head. I’m not blaming social media. Listen, I’m on social media. I love social media. It has its place. But everybody has gotten this really strange sense of entitlement and self-importance and self-indulgence. Nothing wrong with it, but when it takes over your life, which it’s happened to do with the way things have shifted … god, I sound so old. But I didn’t grow up with that stuff. We didn’t have computers. We didn’t have cell phones. We had to figure shit out on our own. We had to talk to each other. There were fights, I’m not going to act like there weren’t. But you figured it out. There wasn’t this super sensitive, super precious culture. We always had a way of talking and educating and learning. Instead of calling somebody out and shaming them, we would find them at the piers and talk to them. What’s missing is the love, understanding, education, and sense of community. I think that we’re making our ego and the false stuff the priority, instead of thinking about others.

STONE: In the context of Drag Race, I think social media is particularly interesting. What do you think about the importance of social media for a drag queen’s artistic expression? Do you think it closes doors, or makes it inauthentic in any way?

VISAGE: No! Here’s the thing with social media—it’s very necessary. But it’s also very dangerous. Social media is absolutely important to drag queens coming up and getting their art form out there. Because it’s art! A painter is showing their painting, a make-up artist is doing their make-up. I don’t think it’s watered it down. If anything, it’s strengthened it. It’s amplified it. It lets their talent be seen because they are artists. I couldn’t understand why my own people, and their own people, could not see that. It was always very weird to me that we weren’t all on board with drag. Social media is fantastic for drag queens.

TRAINOR: What happens to the art of drag when it isn’t so marginalized? Do you worry, at all, about the fact that maybe some of the grit and grime of what drag used to be has been replaced with a little bit of sheen and shine?

VISAGE: What I worry about, in that context, is that people won’t know the history. I think it’s important for people to know the history of drag. If you travel around the world, that grit and grime still lives. Not everybody is going to be able to look like Violet Chachki or Aquaria. There are going to be queens that can’t, and don’t want to, achieve that aesthetic.

TRAINOR: Right.

VISAGE: The grit and the grime is what I fell in love with, so that’s why you’ve heard me say, “Stop relying on that body,” and “I get bored with pretty.” Pretty is great. It’s also very achievable from lots of these queens. They put me to shame. They put a lot of the supermodels to shame. But that doesn’t mean their drag is better. It means it’s clean and it’s unclockable, in many ways. But that doesn’t mean it’s better. You’re calling drag “mainstream”—it’s more mainstream. It’s more accepted. But it’s definitely not Ellen Degeneres. 70 million people still voted for Trump. These are the same people that will not accept gay people or gay marriage or trans people or trans rights. We still have work to do and jobs to be done. Gay history should be taught.

TRAINOR: Let’s talk about Season 13! What was the hardest part about filming Drag Race in the midst of a pandemic? Did it feel different making the show during not only a global health crisis, but in a time of great social and civil unrest?

VISAGE: I think we all felt the heat of what was going on in the world. There was always fear because it’s the unknown. To be honest, it’s still the unknown. There was that. But I tell you what, VH1 and World of Wonder have created the best set to be on, here and in the U.K. People were making fun of us for being so extreme and I’m sure they paid a lot more money than they were expecting to pay in order to keep everything in check, but I have never felt more safe. And then, like you said, there was political unrest. As the LGBTQ community, we are part of the unrest. We are part of the forgotten people that are being pushed aside in this whole situation. It all felt different, but it also felt like unity in a weird sense, because I was with queer people making a queer television show in the middle of a pandemic. These queens really needed to rely on each other and to be in their own bubble. There was a sense of presence that maybe isn’t always there. Consciousness was everything. I’m so glad that we were able to make it because I think it’s a spot of relief we all need right now.