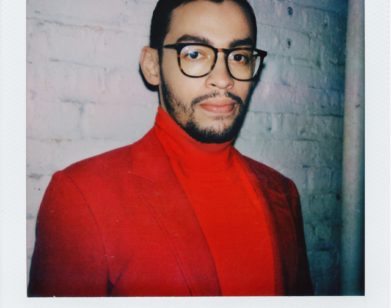

Ask an Intellectual: Masha Gessen on Self-Isolation, Hope, and the Current State of Their Hair

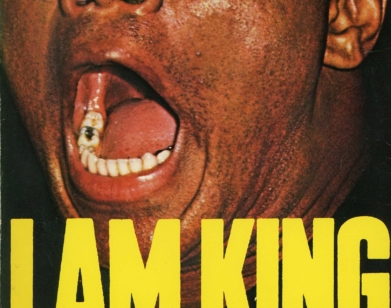

The Russian-American writer and activist Masha Gessen has been one of our most vocal and cogent thinkers in spotlighting the dangers of the current political climate—with democracy ever tipping toward the brink. Their new book, Surviving Autocracy (Riverhead), out next month, is a reckoning with what has been lost in the past few years and a map forward with our beliefs intact.

———

INTERVIEW: Where are you and how long have you been isolating?

MASHA GESSEN: I have been on Cape Cod, in the town of Falmouth, since March 16. We decided to come here because it’s where my father lives, but for the first month and a half, we didn’t see him at all. Then we took a walk—masked and social-distanced, and out in the woods. All of it.

INTERVIEW: What is the worst-case scenario for the future?

GESSEN: A renewal and reinforcement of all kinds of borders—national, state, regional, whatever. We try to go back to exactly the way things were, and this means that the poor get poorer and the wealth gap grows. Two areas that are perhaps most in need of awakening and reinvention—healthcare and education—become worse versions of their already terrible selves. We learn nothing except that no one will help you.

BOLLEN: What good can come out of this lockdown?

GESSEN: It’s hard for me to imagine that the lockdown itself can be productive. I think it’s exhausting and deadening to the soul. But I have hope for two kinds of writing: journal writing of the sort that Laurie Stone practices—intensely observant of self and circumstances and associations—and what I have been thinking about as writing about the “after,” a project that requires immense imagination.

INTERVIEW: How will world governments be remembered for their responses to the pandemic?

GESSEN: It all depends on who is doing the remembering, doesn’t it? One thing to keep in mind is that we are unlikely to remember anything that we are failing to see right now. In history, things rarely become clear in retrospect: if we don’t get things in writing, on film, or otherwise recorded now, they are likely to be elided. So, it’s very important to continue to notice the ways in which our government is failing us, even if those ways have become familiar and exhausting.

INTERVIEW: What has been your daily routine during this time?

GESSEN: On a good day, I manage to: spend a bit of individual time with each of my three kids (8, 18, 21), do some exercises with dumbbells, take an hour-long bike ride, read student work or teach a class by Zoom, do some of my own writing, and cook dinner and eat with everybody. On a bad day, I have consecutive fights with everyone in the house, except, usually, the 8-year-old, and they fight with one another, and nothing gets done except some dumbbells and the dinner.

INTERVIEW: Describe the current state of your hair?

GESSEN: I would prefer not to.

INTERVIEW: On a scale of 1 to 10, what level is your level of panic about the current state of the world?

GESSEN: I am beyond panic.

INTERVIEW: What is your favorite novel, film, or album for self-isolation?

GESSEN: I am reading Lydia Chukovskaya’s journal about [the Soviet Russian poet] Anna Akhmatova, in Russian. I read it as a teenager and wanted to re-read the parts about living in Central Asia during WWII—they were evacuated there, so these are descriptions of life away from home and also away from the battle, in the rear, and yet their lives were entirely defined by the war. On the long train journey to Tashkent, Akhmatova is reading Through the Looking-Glass and asks her travel companion, “Do you think we have passed through the looking-glass?”

INTERVIEW: Who would be the worst person to spend a month of lockdown with?

GESSEN: The list is very long. It includes most people.

INTERVIEW: If 2020 were a song, which song would it be?

GESSEN: For me, it’s Muzak. Self-isolation is to life what Muzak is to music—pale, bland, predictable, and endless.

INTERVIEW: Where did we go wrong? Like, what was the exact moment?

GESSEN: I think there are many moments. But certainly, our responses, as a nation, to 9-11 and to the financial crisis of 2008, paved the ground for this, as has our persistent disregard for the climate crisis.

INTERVIEW: State vs. federal? Who should have the power to control the movements and reopening of economies for its people?

GESSEN: If I am answering the question as asked, then I would say that there ought to be sane national guidelines within which states and municipalities make decisions based on the local situation. But more broadly, I really wish we were using this time to think deeply about the interconnectedness of the world and the artifice of state and national borders. A vast number of policies have been based on a kind of magical idea that the virus can be stopped at the border, or a border. We know that that’s not true. So what’s a better way of thinking about it?

INTERVIEW: Is this circumstance a win for technology or for the value of real human contact?

GESSEN: Both. I am, of course, grateful for Zoom and social media, which have allowed me to continue working and, to some extent, living in the world. But I think by now we all understand what a poor substitute they provide for actual human contact. Don’t we?

INTERVIEW: What prevents you from giving up hope in the human race?

GESSEN: I plan to spend the rest of my life with it.

INTERVIEW: Who should be the next president of the United States?

GESSEN: Elizabeth Warren. For one thing, I’m pretty sure she has never raped or inappropriately touched anyone. For another, she has a plan for everything. But seriously, she is brilliant and able to think fast about complicated things. We need to reinvent so many things so fast: the welfare state, health care, and education, to name the three big ones. And we need to move fast, and radically, on energy policy and, more broadly, climate policy. She could do it.