Batali Royale

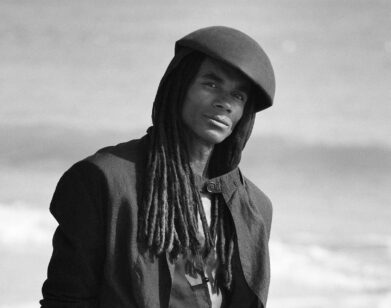

ABOVE: MARIO BATALI. PHOTO BY GARTH VON GLEHN

Tradition and authenticity are synonymous with the work of chef Mario Batali, who’s prolific in the way that only the truly passionate are. Among his many establishments, Del Posto was the first New York City Italian restaurant in 36 years to gain a four-star review from The New York Times. His Italian food emporium, Eataly, now ranks number three in the tourist destination poll in Manhattan (following the Empire State Building and the Metropolitan Museum of Art).

There have been cookbooks and Food Network spots, too; at the heart of his industry is a cultural nuance unlike anyone else’s. We caught up with Batali in his Greenwich Village spot, Otto, and drank spectacularly strong espresso.

DOMINIC MAXWELL-LEWIS: “Everything old is right, everything new is wrong.” What made you say that?

MARIO BATALI: I think that probably came out of… [pauses] that the pendulum of cookery techniques became more significant than the actual experience. And when that happens, the customer’s satisfaction becomes secondary to the chef’s satisfaction. And in that case, you have an upside-down equation. Because the customer is the basis of our restaurant, first of all, and if the chef becomes the most important person at the table—even more so than the guests—then suddenly you’re left with something that doesn’t really work. What I like to do when I go out is enjoy my friends and the food around it. If we have to stop and give five minutes to the chef, then I’m down with that. But if the chef has to interrupt every course to tell us how important this new revolution that’s happening is, then I’m not so much interested in that.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: You don’t like the chef monologue.

BATALI: No I do… if I want to hear it. And if I’m by myself, or if it’s just me and two friends, then fine. But if we went there because we’re individuals that want to discuss something besides the dinner and we are left to just enjoy the dinner, then that would be nice.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: Community and food seem to be unifying themes in Italian cooking.

BATALI: Worldwide cooking!

MAXWELL-LEWIS: Well, yes. But what I’m drawing on is the received wisdom of films for non-Italians.

BATALI: And Barilla commercials…

MAXWELL-LEWIS: [laughs] Right.

BATALI: When the music wells up and the children are perfect and Mommy makes spaghetti and Daddy opens the wine… It’s the great experience! But it’s also the great Italian myth. Now, of course there’s normal disharmonies in every Italian family, but at the end of the day, the idea of having dinner together every day with your family removes the pressure from trying to explain everything. You tell us the good parts about your day, but you also tell us the bad parts about your day. And at the end of that, because you’re in a ritual, you remove the pressure of admitting you had a failure that day. And it also takes the wind out of having a great day. I mean, it makes you a little bit more normal all the time. That moment of therapeutic sharing is something that happens in food, that doesn’t necessarily happen when you’re watching TV.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: There’s a reliability with the ongoing dialogue.

BATALI: Right. There’s a consistency of feeling in your heart that allows you to diminish your guard a little bit, and share. It’s the best time for me to figure out what my kids are doing. Right after you wake them up at breakfast, you pepper them with questions. You can get in there because they’re not protecting what they thought was cool: “What happened yesterday?” “Oh, Matthew stole my book and ran away and it was really annoying…” That wouldn’t happen after lunch, because their defenses are up. In the morning, if you lull them into a comfortable place, you get more honesty, and that’s without being a detective.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: Sneaky… I wanted to talk to you about regionality as an ideology. There’s such a strong identity at Eataly. It’s like an Italian Narnia. How do you begin to cultivate something like that?

BATALI: Eataly wasn’t our original plan, but Italy was in our plan. And it’s that when people think of Italian food, they think of spaghetti, lasagna, Ciao!, meatballs. Italy itself has 21 different micro-regions. You go within each of those regions, there’s even super-micro-regions; and the beauty is that when you go from place to place, although there’s a common thread of pasta and joie de vivre—in the way that they approach their meals and the simplicity of cooking, celebrating more the product than the chef—there’s still so much variety that as you go, it’s always an exciting moment. Even though you’ll see gnocchi or linguine everywhere in some of those regions, each of those chefs has their own expression of that which expresses more about the place they were exactly born than it does about trying to be a part of the greater mass. And that’s the Italian culture.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: Do you view yourself as part educator as well?

BATALI: Well, I’ve been lucky enough in 20 years in the media to have a nice soap box that put me in a position to describe to an American viewership that Tuscany is different from Umbria, and it’s different from Emilia-Romagna and, not that that was news, but it was never presented to them in a way that was, “Hey, look. This is a different plate from that different place.” And although we all think of “spaghetti, lasagna, ciao,” as what Italy is all about, there’s all of this great stuff… I was merely an interpreter. I wasn’t the developer of the content.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: How do you distribute your time amongst your restaurants?

BATALI: The squeaky wheel gets the grease. [laughs] If I hear something’s not quite going right, then I’m there quicker than if I hear something’s going wrong. Sometimes it’s about an elevated expectation, and other times it’s about flaws in our system and we have to fix it. But my rotation is generally by proximity to my house. I spend time here more often because I live across the street. Babbo the next closest, Lupa the next closest, Casa Mono the next closest, Eataly the closest after that, Spotted Pig, Del Posto… they’re all in the range. I’m at Del Posto once a week, probably at Babbo four times a week, and I’m at Otto every day.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: What do you make of the new wave of American gastronomy that’s finding its way here via food-truck culture before establishing bricks and mortar?

BATALI: I think any way of getting people into the field by lowering the threshold of the cost to get them to play, is great. That said, there’s all these restaurants around that are very popular that have one menu. And they don’t even have tables, and they don’t even have backs on their chairs. It’s not really the experience I’m after, but I’m happy they exist.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: Just to touch back on food as education. What do you think of gastro-crusaders like Jamie Oliver blazing across America?

BATALI: I think that there is philanthropy and there is publicity. If you can marry the two to do something good, then I think it’s great. Some of the other guys go around and slag people as a profession. That’s not so interesting to me, because it’s easy to take down, it’s harder to build. I’m a full supporter of Jamie’s initiatives, but I’m not sure he saw the success he hoped. It’s not about changing the world, it’s about raising awareness. And there’s no question he raised awareness.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: I wanted to talk to you about urban agriculture. A lot of restaurants get their produce from upstate, but what do you think about trying to bring it closer to the heart of the city?

BATALI: I love that. I think the more prominent the actual product in its raw nature is to its final consumer, the more sympathy and likelihood they’ll consume it they’ll have. Some friends of mine are trying to do these rooftop farms in Brooklyn, and I love that idea. As long as they’re using clean water and real soil and creating delicious things by the sun, then brilliant. I mean, if you go to Italy and you drive from the airport to the town, there isn’t 30 square feet that isn’t planted by someone. Even next to the train tracks, they see the joy of the interaction with the planet as integral to the experience. The idea that you can get free arugula just by planting seeds… because it will regrow itself the next year. We’ve come a long way from foraging to now planting. The next step of that will be continuing that expansion of planting and really owning the crops.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: How much time do you get to spend back in Italy?

BATALI: I was there this weekend. I was in Rome for Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. But I go four or five times a year just for a weekend, just to see what’s going on. Sometimes for relaxing and enjoying, but I’m considered an “opinion leader” these days in Italy so they’ll bring me over to taste their new gelato.

MAXWELL-LEWIS: Do you take your kids?

BATALI: Not, if we’re in the middle of school year, because “you can’t replace those school days…”

MAXWELL-LEWIS: Are you building an Italian identity with them them that’s as strong as yours?

BATALI: I think they get it. They understand it. But their mom’s Hungarian-Russian-Eastern European-Jewish, and they feel very attached to that too, which is a perfect marriage of worlds. But I don’t think they long for pelmeni or goulash as much as they long for ravioli or pizza. But it’s there and it’s important that they realize it’s not just dad or mom or whoever’s on TV, it’s understanding the tradition that your family brings from all of its roots.

MARIO BATALI WILL SPEAK ALONG MICHAEL SYMON AT A TIMES TALK THIS SATURDAY AS PART OF THE NEW YORK CITY WINE & FOOD FESTIVAL. FOR MORE INFORMATION ON THE EVENT, PLEASE VISIT THE FESTIVAL’S WEBSITE.