HOT LIT

LA Warman Doesn’t Believe in Lesbian Bed Death

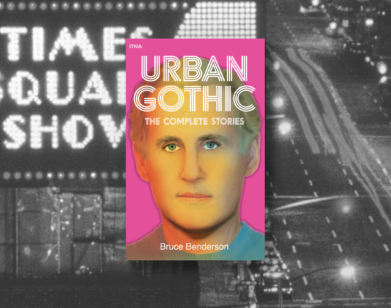

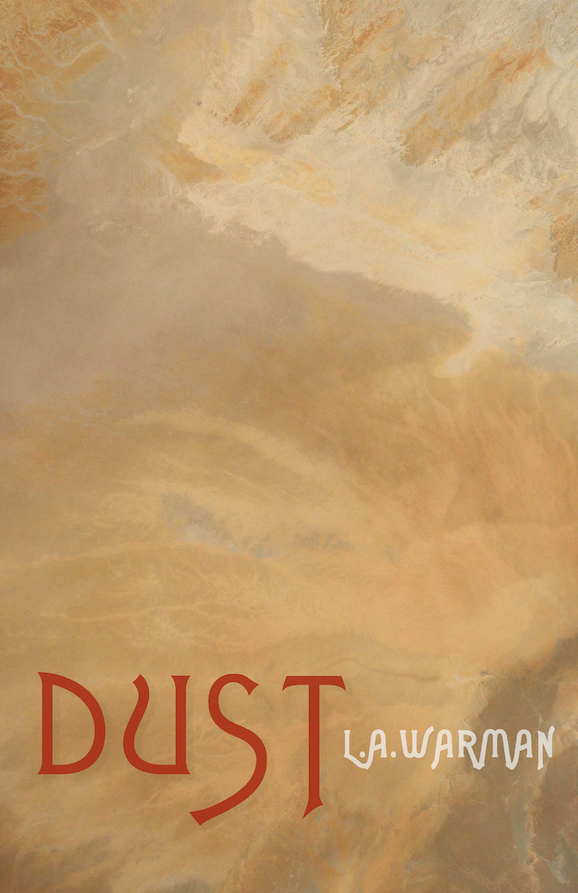

LA Warman, the Brooklyn-based poet and founder of an eponymous writing school that offers classes like “GOD !!!! ????” and “DEPRESSION” is back with a Dust, an “anti-sequel” to her smutty, award-winning debut novella Whore Foods. Dust follows a pair of unnamed women on a sexual odyssey through a post-apocalyptic desert wasteland, where they fuck like the world is ending while surviving off of vapors from shadowy, extraterrestrial “Visitors” until they get tired of living. To dig deep into Dust, death, and the erotic power of saying no, Warman sat down with her girlfriend Yulan Grant, the DJ and multidisciplinary artist better known as SHYBOI.—CAITLIN LENT

–––

YULAN GRANT: How are you doing, LA?

LA WARMAN: I’m okay, it’s nice to see you!

GRANT: Nice to see you too. Okay, so now that some time has passed since Dust has been released, do you feel differently about your book now than when you first finished?

WARMAN: Yes. A lot of the book is about isolation and caretaking and grief, so it was solitary. As I emerge now, it’s shocking because other people read it and tell me about it. It’s no longer mine or about me.

GRANT: When you were speaking, a word that really stuck out to me was “caretaker.” How do you feel about the caretaker role, and is it something you find yourself in?

WARMAN: That was the origin of the book. When my mother got sick and I started taking care of her, I don’t want to say despised—that sounds really strong—but I hated the role. I was thinking about the role of erotics, and what would erotics be like if all of our needs were taken care of, which is kind of the origin story of the Visitors in the book. Also, a lot of erotics are how one is being seen and perceived and processed, so what is desire without witness?

GRANT: Could you delve into the erotics of grief, and how that relates to your work?

WARMAN: Yes. Grief, as I’ve experienced it lately, feels like pure body. The emotions are too powerful for language. When grief is fully expressed—that’s when you are able to be fully in your body. In my experience, and almost everyone’s experiences, the erotics are an early space of trauma and sexual violence. So, emerging from that to reach a state where one can be fully in their body, that’s what I’m always trying to do. I’m always failing. I don’t know if I’ve ever been fully in my body, but that is something grief unlocks for me.

GRANT: Is that something you try to accomplish within your classes at the Warman School?

WARMAN: Yeah, that’s the way I teach. We do a lot of movement activities and body exercises. A word I’ve been using a lot recently in my movement activities is wobble, I’m thinking about ways to not be so steady.

GRANT: I really like that you use the word wobble because I feel like there’s a lot of musicality within this book, and there’s a rhythmic nature to the way you write. I’m wondering how you view the sonic aspects of it, because reading it and hearing you speak it provides such a different experience.

WARMAN: I want to say that’s something that I learned from you, because you do music performance and you create alternate realities through sound experiences and movement. That’s something you’ve taught me.

GRANT: You’re welcome. Do I distract you when you’re writing?

WARMAN: Yes.

GRANT: Oh. I don’t think I do.

WARMAN: You don’t think you do?

GRANT: Do I?

WARMAN: It’s funny because I wrote a lot of this book in our house together, but our desks are on opposite ends of the house. I remember sometimes I would just want to go see what you were up to, or kiss your arm or something, but I knew I had to finish writing a passage, so I’d try to write, write, write, so I could get there faster. That is distracting. You loom large in the book. You’re kind of the book, and that is because of the ways in which you challenge my sense of self. You taught me not to take care of everyone else, to look inwards first. Also, just because we’ve dated each other for a long time, over—

GRANT: Do you not know how long we’ve been dating? [Laughs]

WARMAN: Is it over four years?

GRANT: Yeah. [Laughs]

WARMAN: That’s wild. It’s my longest relationship. One of the coolest parts of it is that I will never know you completely. I am always learning something new. We’re both always changing. A lack of stability for me is often scary, but that’s why we can still be together. Also, during the pandemic, my body changed a lot. It grew and grew and I was thinking a lot about that and how desire can take on so many different forms. That’s erotic, that’s arousing.

GRANT: You wrote most of Dust at the house, but do you have a preferred place to write? If there wasn’t a pandemic happening, would you have been writing somewhere else?

WARMAN: I definitely enjoy writing in other places. We took a lot of trips to the desert and the hot springs, that’s kind of our place. I would take notes on my phone when we were there. Some of my favorite scenes of the whole book I wrote in public. The other day I went to The Bramble in Central Park, which is, like, a historic cruising spot, and I wrote a scene about rocks. I was just laying on the rock and feeling its warmth. Going to spaces like that feels important because it’s a way in which I can commune with those that we’ve lost. And I definitely wrote a bit at Bossa Nova Civic Club and Cubbyhole, the lesbian bar. Cruising spots, hookup spots, spaces of potential erotic interaction, and your house—when you used to live down Putnam—all those different spaces are important to me.

GRANT: Are you envisioning sexual fantasies within these spaces and that’s how they come into the book?

WARMAN: They definitely conjure fantasies that I then want to write about. It’s collective erotics. I love writing erotica because it’s exhibitionist. Also, I have to demand lesbian presence in cruising spots. There are a lot of ways lesbians are interpreted throughout history. We are seen as not sexy, or not hooking up. Lesbians are cruising, lesbians are being nasty, and lesbians are hooking up with randos and fucking and being depraved.

GRANT: People don’t think of lesbians having sex. And there’s always the age old stereotype of lesbian bed death. How do you feel about that?

WARMAN: It’s one of the funniest phrases I’ve ever heard. I think about it all the time because one, it’s “bed,” as if a bed is the only space for sexual interaction. And then the idea of death, that lesbians don’t have sex at all—I remember how there were no homophobic laws saying women couldn’t have sex with women because they didn’t think it was possible. It’s fun to have all these little secret spaces of nastiness and desire and for it to be seen as death. How embarrassing for them that they can’t see what’s actually taking place.

GRANT: In Dust, there’s this constant recurrence of denial. It’s more than the physical act, it’s creating this whole world that’s very BDSM.

WARMAN: I love the word “no.” I love edging. I love being denied desire. There are so many spaces in which I wasn’t allowed to say no, so now it’s the most arousing thing to say. That’s what’s nice about partnership. There’s so much room for no and yes and maybe and figuring it out.

GRANT: Now I’m just going to say no even more.

WARMAN: Yeah, I love that. You’re really good at saying no.

GRANT: Am I? I feel like I could be better at saying no. But if I could, I’d say no to everything.

WARMAN: Exactly. That’s our new mantra, just say no to everything.

GRANT: No. Yeah. Feels good.

WARMAN: Say it again.

GRANT: No.

WARMAN: Say it again. [Laughs]

GRANT: No.

WARMAN: [Laughs]

GRANT: Anyway, when I was reading the book I just kept crying. Tears were just streaming down my face. I feel like you have this power to make people cry. That’s kind of freaky. Having that experience while reading erotica is not something that has ever happened to me before. It was kind of disorienting.

WARMAN: That’s the number one comment I’ve heard, that it makes people cry. I definitely cried a lot while writing it. But I wasn’t really expecting that, especially with it being my second book of erotica and my first one being goofy, grocery store erotics. This book is the depressed sister of my first book. I wrote it from a space of intense grief and sadness. I don’t want to be a downer but I am a downer. But crying can be positive. For a while I got really disconnected from my body so it’s like practice to return into it. For someone to be able to connect with my writing in a bodily way makes me feel lucky.

GRANT: Do you think being a death doula influences your writing? If my memory serves correctly, you were doing death classes at the Warman School before you started your death doula training, right?

WARMAN: Yeah. When my mom got sick, I was reading and writing about death, and nobody wanted to talk about it. So I was just like, “I’ll make a space where we can talk about it.” I naturally follow whatever fucked up shit happens in my life. So, my mom is dying, I’ll do death stuff. I’m traumatized by the evangelical, white supremacist faith, let me research that. Whatever happen I follow it, especially stuff that makes me upset or sad, or that forces me to exit my body in different ways.

GRANT: So, I know you have to teach in a few minutes and I want to give you time to decompress from this, but is there anything else you’d like to add?

WARMAN: Yes. I love rocks. I love dirt and sand. I hate the phrase “dust to dust.” I want to eat dust. I love eating rocks. Sometimes skin tastes like minerals—I think most of the time it does—or salt. I want to lick you in the ocean, and lick you on a sand dune. One of my best memories is you rolling down a sand dune, screaming, with your legs in the air. Your hat looks cute, you’re in a nice sunbeam. Buy Dust.