LIT!

Bruce Benderson and Juliana Huxtable on Bataille, Bathrooms, and Bachelorhood

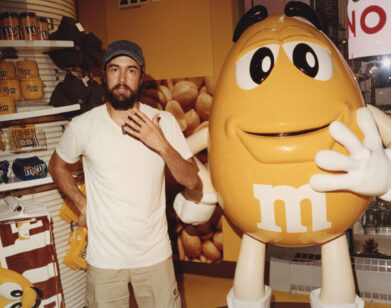

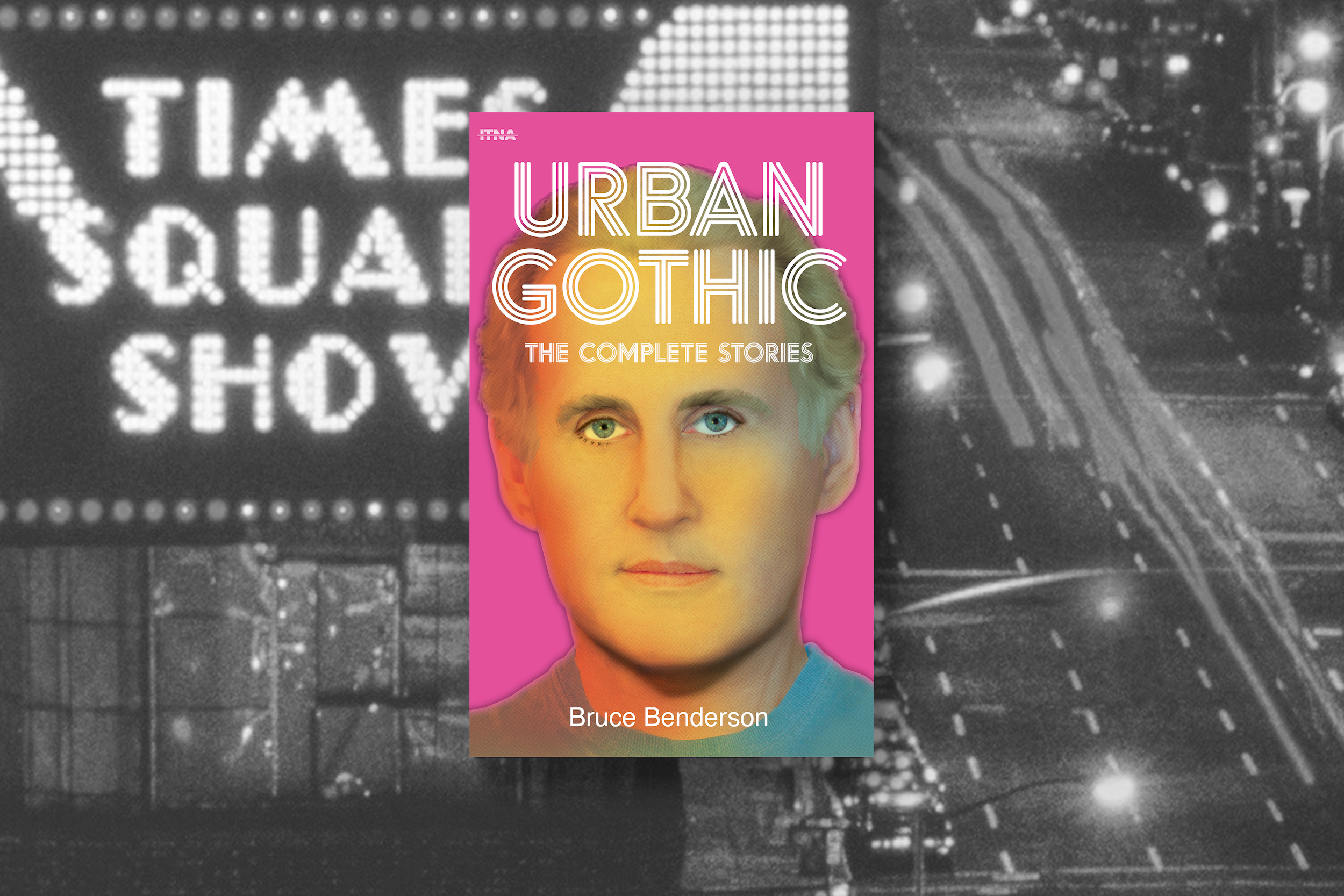

Bruce Benderson began visiting the New York underworld on August 6th, 1985, frequenting queer hustler bars in yesteryear’s seedy Times Square, visits he’d later fictionalize in books including Pretending to Say No (1990) and User (1994). His newest release from ITNA Press, Urban Gothic: The Complete Stories, organizes every short story he’s written over his career into nine non-temporal sections across 670 pages. Launched alongside a recently written novel, The Virtuous Ones, by the press’s founder Christopher Stoddard, Urban Gothic reads as contemporary as any new collection while condensing Benderson’s exuberant experimentation in literary form and salacious reality over the past several decades. In novels and non-fiction books including Sex and Isolation (2007), Pacific Agony (2007), and the Prix de Flore–winning The Romanian (2014), Benderson has remained incorrigibly attuned to the contradictions of bourgeois society and its mores—sexual or otherwise. With this in mind, Interview asked him to meet artist, writer, and musician Juliana Huxtable. Coming of age in an era when Benderson’s preferred underground spaces were being elided with online life, Huxtable’s art and writing slips between IRL and digital logics deftly, amalgamating creative typologies with equal measures of intellectualism and humor. Both subvert language’s potential to not merely represent but to transgress the structures and strictures mediating our relations to one another. Bataille, bathrooms, and bachelorhood—Benderson and Huxtable volley over the highs and the lows of culture and its discontents.

———

BRUCE BENDERSON: Hello.

JULIANA HUXTABLE: Hi.

BENDERSON: Well, Juliana, I must say that when I started researching you I got so fascinated that I was just ready to say, “Let’s forget the whole thing and jump into bed together.”

HUXTABLE: I don’t know if you read my responses to your email.

BENDERSON: I started to, but I think we don’t need it. You can just say whatever you want.

HUXTABLE: I did begin by reading the preface of your book, and I do think that it’s a useful and/or interesting place to start from the role of language and evolution in language and what it means to look back. If there’s an idea that the evolution of language should have some ethics behind it, what does that mean in terms of what language is supposed to do? I’m not a person that can be offended, but sometimes it’s hard to tell where a preface about a relationship to cancel culture—the plethora approaches to language that can entail—can go, but I didn’t even feel like I had to do the work of saying, “Well, this is in the context of the time period. So that’s why I’m able to interface with the book without feeling an unpleasant edge.” I really enjoyed reading all of the stories.

BENDERSON: May I compliment you back? I did research on you late today, but the more I read, the more my jaw dropped and my eyes widened and I thought, “Oh my god. I could talk to her for hours about these issues. I had no idea that anybody thought about them like that.”

HUXTABLE: Oh, I’m honored. My best friend Riley actually gave me a book of yours not too long ago. I haven’t read the book yet, but I’m really happy that Urban Gothic was my introduction to your work. It’s such a vivid, intense entryway into your writing—into your approach to writing.

BENDERSON: It is.

HUXTABLE: I think that I have a fetish, to a certain degree, for the integration of violence and desire, and the relationship between violence and desire and revenge and love and how these things intertwine, but outside of a meta-narrative of a grand romance. And that was one of the first things about the stories that really struck me. It immediately made me think of Frantz Fanon and Wretched of the Earth, which is really trying to grapple with the role of violence. It made me think of Fanon’s writing in a different way, violence is a constitutive part of the structure of the colonial experience, and I think that extends into so many different cultural strictures. The way he writes about the dance circle and the seance as this way of carving out an intentional cultural space around violence, I thought there was a parallel within your writing.

BENDERSON: Let me stop you because it’s raised so many things that you’ve mentioned in passing. First of all, what you have just been describing in my opinion is Bataille. That is Bataille’s theory of violence and eroticism and the sacred and how they interact. He’s my favorite philosopher.

HUXTABLE: Bataille’s also my favorite philosopher

BENDERSON: Oh my god!

HUXTABLE: The Accursed Share is my bible.

BENDERSON: We were meant for each other. I want to bring it back to the personal because you mentioned “colonial,” and until recently, when people began deconstructing what colonialism really was, colonialism had many opportunities for the bachelor, for the white middle class or above bachelor. And I thought, “Well, I’ll always be somebody who lives in North Africa and takes advantage of the pleasures that are there for people like Paul Bowles. I’ll be a Paul Bowles type.” Or in New York, I’ll live in what used to be called a bachelor hotel, which means that there’d be a restaurant below that would bring up the meals and there’d be a maid once a week to change my disgusting sheets, and my entire plans for the future I only realized later were based on colonialism. I know better now, but isn’t that interesting?

HUXTABLE: That is interesting, and I think the colonial dynamic as a form—if you can think of that as a form of violence—once it’s introduced into a social, cultural, political context, you can’t get rid of it. Maybe this is a little bit oversharing in terms of what some of the texts I read that brought up in me, but I just got out of a relationship that was really raised a lot of fundamental questions about my approach to sex.

BENDERSON: Well, I’m so glad to hear that you’re available again.

HUXTABLE: I am indeed. I’m very, very, very available right now. I watched a video interview you did talking about the city as a meeting place of different classes. As a place that’s really generative and particularly exciting for unmarried people, people that exist outside of family and/or traditional couple dynamic.

BENDERSON: Totally. That’s in my book Against Marriage. Exactly what you said. Oh, you are so fucking smart. You really are, and I just wanted to add something to that about people going to the cities. That’s why I am against marriage. I am not against gay marriage. I am against the intrusion of the sacred into the political. I am for the separation of church and state and I don’t think that marriage should have any legal value. People are free to have their sacred little things, but the moment that now that gays have been absorbed in the marriage, I’m ten times more alienated as a single person, and the only reason I came to New York was because it was a haven for creative single person to have a life. In the suburbs you gotta have a family, family values, all that shit.

HUXTABLE: I grew up in the country, it’s a small town in Texas, but there was a Walmart and a McDonald’s, so in some ways it was suburban. I think the ongoing conversations around the disappearance of gay bars as spaces brings up a lot of important questions, but at the same time, for me growing up in the middle of nowhere, the internet allowed me as someone that had an intuitive desire for sexual exploration and degeneracy to find that. It didn’t produce the social spaces. I couldn’t go to a physical place and meet people, but the internet provided an opportunity for me to meet and fuck and have really evolved dynamics with people that I otherwise wouldn’t.

BENDERSON: My indoctrination was many years before the internet. It was the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s, so I did not learn about anything online. I learned it by straying into the men’s room of the main library in Syracuse where I was growing up, or going to the bus station to that lavatory—and I was underage, but I met these very kind middle-aged men who taught me that it was okay to be homosexual and how much fun it was to be, so I learned everything IRL.

HUXTABLE: I was mentioning this because of the way you write about these spaces where all these different people were coming together. I love the first story in your book, the relationship between the Vietnamese trans woman and the blond boy.

BENDERSON: She’s a madame of a trans brothel in Atlantic City and she’s based on a real person. I’m waiting for her to read it and kill me.

HUXTABLE: The slippage between all of the characters and the relationship between them… I was legitimately shocked at the end to find out that she and the blond boy had a thing.

BENDERSON: I made it up. It’s fiction. I knew someone like her and I knew someone like him, but she didn’t throw acid in his face.

HUXTABLE: I obviously never experienced Times Square at that time, but I was really excited by virtual space. I think of my generation, all of the real perverts that I know were on Craigslist at some point, because it was this interstitial space, even for someone like me who growing up who for a lot of reasons didn’t relate to gay spaces. There was a gay bar in the town next to mine. It was the only gay bar in a huge radius, and me and my friends would go because it was fun and that’s where the weird people hung out.

BENDERSON: The weird people. That was what was so wonderful about these provincial bars, they caught everything. If it was a small town like in Binghamton where I went to college, there was only one gay bar. What was in that gay bar? Not just gay men, but also a few homeless people, also a few addicts had been rejected by the families, a lot of lesbians. It was a big conglomeration of all the outsiders.

HUXTABLE: I’m glad that I got to experience the last vestige of that. I do think in Texas it’s still—yes, there are internet communities, but in my hometown I think a lot of people still need physical spaces because the population is so small that, for the technology, there’s not enough of a user base. Growing up we found them in coffee shops. That was the closest thing to signaling alternative culture outside of the gay bar that was only open one day a week. Even then you had to sneak and people would try and beat you up if you were walking to the gay bar.

BENDERSON: Chat rooms on AOL. Do you use them?

HUXTABLE: Yes, I did Yahoo chats. I was a cam girl. I did AdultFriendFinder. I did Alt.com. I had FetLife, any website, any kind of desktop web browser sex site I was probably on starting from when I was 14.

BENDERSON: Darling, weren’t your parents watching?

HUXTABLE: I was raised mostly by my mother after my parents got divorced, and my mother was bipolar and schizophrenic and extremely conservative, which has produced neurotic avoidances. I remember one time my mom warned me about how I use my screen names, because anyone can look me up on the internet, and I was like, “What is she talking about?” And I googled my AIM screen name and the third thing that came up in the search results was my Alt.com profile. I know my mother was completely losing her mind. She’s a conservative, draconian, highly, super, extremely physically abusive woman, but she would not confront and could not deal with the idea that I as a 14 year old had a—

BENDERSON: Darling. You have suffered.

HUXTABLE: My childhood was not great, but I’m very thankful to the internet—well maybe that’s a stretch, being thankful to the internet as some whole entity.

BENDERSON: My parents were almost like immigrants. My mother had been born in Russia. They’re both Jewish, East European Jews, and she had come to the U.S. at the age of two and I had the most coddled upbringing because after their immigrant experience, the depression, they didn’t want their children to feel the slightest stress from anything. I never even saw the Black neighborhood in Syracuse because I didn’t meet Black people till I came to New York, which was partly why Times Square was so incredibly exciting for me, because they were Latinos and Blacks and I had been completely isolated from them by my parents because those neighborhoods were quote unquote “dangerous.” I wasn’t even a human being till I moved to New York.

HUXTABLE: How did your experiences in New York expand your writing or ignite them?

BENDERSON: A really simple answer. When I got out of college, I came to New York for just six months, and then moved to San Francisco for five years and got on welfare immediately like all the people around me did. I was best friends with The Cockettes and other underground gay types. We ran around half dressed as women with our cocks hanging out, maybe we put glitter on our cocks to make it a little more feminine. Since I was on welfare, I had five years to develop my writing craft, and that’s when I learned French too on my own by reading bilingual editions of Baudelaire and Rimbaud and all that. I tried to start a novel, but I wasn’t mature enough, and I’m actually working on that novel now! Because I re-found it, the manuscript. But the thing was, by the time I moved back to New York five years later in 74, I already had a pretty good education as a writer on my own from the leisure afforded by being on welfare. [Laughs.]

HUXTABLE: I wanted to ask you about what America symbolized over the time that you’ve both been living and writing. The role of commerce and the interplay between money and these fluid slippages between all of the characters and their sexualities was really pronounced to me in a way that was very particular to your writing, but then also there were these moments where, for example in the story with Trixi and the Countess, and—

BENDERSON: Perdido. The story’s called “The Old Switcheroo.”

HUXTABLE: When the characters are on the plane approaching the island and the other people on the plane are looking at Trixie’s polka dot dress as something that they were even surprised because they would’ve thrown it away. Perdido says, “Maybe it’ll change their idea about America being so hoity-toity.”

BENDERSON: That was a joke. The woman he travels with is dressed in a vulgar way and his reaction is, “Well maybe they think we’re less hoity-toity now.” It’s a totally racist remark, right? I’m parodying that mentality. I hope no one thinks it is my mentality. It is in a way, because I grew up with that everywhere, on television and books, but I’m distant enough from it that now it’s a joke to me, people who behave that way.

HUXTABLE:I thought of that in contrast to now. In a weird way traveling as an American people project so much onto you it’s almost like Americans are just a walking joke or the assumption is that you should feel that way. And I hate America as much as I am a product of it. It’s interesting to read and see America in a period of its booming cultural hegemony where maybe now, even if that’s functionally still happening in certain ways through music, it definitely doesn’t have the same color.

BENDERSON: You have expressed that so well, it’s exactly what I think. You see, I went to France, my stuff was discovered in France, and I had a ten times bigger career with the French than I had with Americans, so what do I think of America? I think they’re stupid.

HUXTABLE: I would agree mostly. I’ve never felt within the context of my friends in a certain milieu in New York I’m unappreciated, but in a larger context I was like, “What do I have to do to get people to even engage?” And it’s funny that leaving and living away and traveling and then coming back with a reputation built—for me it was in Germany—became this lubrication to my ability to have a career in New York.

BENDERSON: Berlin is dear to me only because it has a couple hustler bars. But I can’t handle it that well because I was brought up Jewish, so that’s what I feel about everything else. The Holocaust, they’re sorry about it, they’re guilty about it—that’s the main feeling I get when I’m in Berlin.

HUXTABLE: Right, and that is very palpable in Germany.

BENDERSON: But sexually it certainly is a nice place, even for ugly old man such as myself. Maybe we can end with this: why are we supposed to do good rather than bad? I so often wonder that. We’re trying to be fair, we’re trying to be equal. Why?

HUXTABLE: Fundamentally for me the why is that when you suffer, it’s hard to not see the suffering of others. The more one suffers, the experience of suffering breeds almost instinctual empathy, and that’s almost contagious in a certain way. Which isn’t to say it should be the singular ideology, but that I understand at least its presence.

BENDERSON: You’re right, but now you’re going to have to be a Christian because of that.

HUXTABLE: Oh no, no, no.

BENDERSON: The golden rule darling. Do unto others as you wish them to do unto you. You’re a Christian then.

HUXTABLE: But I think you can separate the realization or that feeling of suffering from an imperative. I think the imperative is a few steps removed from the feeling that I have suffered so I don’t want someone else to suffer. That’s different, because that also doesn’t necessarily mean I prosper so I want someone else to prosper in the same way.

BENDERSON: What about I suffered so I want someone else to suffer?

HUXTABLE: I would argue that’s the Christian mentality.

BENDERSON: Really?

HUXTABLE: This is one of the things I dislike about Germany so much, because I think the combination of a Protestant mentality with the East German history of socialism breeds a resentment of excess, it breeds a resentment of glamor. One of the reasons why I can’t live in Berlin a hundred percent of the time is after doing three years there, I needed New York because glamor and aspiration are beautiful, necessary. I’m obsessed with them. I have to have them in my life.

BENDERSON: Me too, and I have to tell you what my mentor, the writer Ursule Molinaro, who’s originally French but became an American writer, she was an old lady with long black fingernails and she could barely walk in her stiletto heels, but she never wore anything else. She told me, “Do you know that glamor and grammar come from similar roots?”

HUXTABLE: Maybe that would explain why the Germans are perverts because they’ve corrupted the relationship between the two.

BENDERSON: Early in my career they did this whole arts section in this Queens Newspaper about my novel User, which is about Times Square junkies and transsexual prostitutes and all of that. The guy came to my house to interview me and I happened to have moved in an apartment that had a renovated step-in shower with all these dark blue tiles. It looked rich. He went to the bathroom, when he came out he said, “And what is the king of the underground doing with such a classy bathroom?” And I said, “Do you think that I want my lovers from the street to have lousy toilets and lousy showers? I want them to have the best they can have. I want everybody to have the best they can have. I’m Oscar Wilde!”

HUXTABLE: Absolutely. Have you ever read Oscar Wilde’s serial column he did on fashion? One of the qualities of your writing that I really love is the way there is ornamentation or a sartorial vision of the world that doesn’t treat it as a surface to something else. I’m looking for that a lot in writing. Writers that understand the complexity of a sartorial sensibility that is just as allegorical or dynamic as anything else. It’s not fiction at all, it’s just Oscar Wilde musing on the fashions of the time, like what the bustle to hip ratio means.

BENDERSON: Have you ever read his essay on socialism? His idea was that everyone deserves a luxurious life with as little work and it as possible, and once machines are developed enough that will be available to everybody. That was his idea of socialism.

HUXTABLE: I actually haven’t, but now I will add that to my list.

BENDERSON: Yeah, it didn’t turn out that way, did it?

HUXTABLE: It definitely did not.