lit

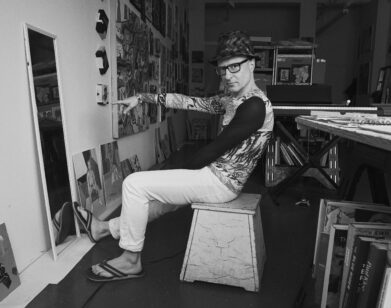

Kamala Puligandla Writes in Zigzags

As the Editor-in-Chief of Autostraddle, the progressive queer feminist site, Kamala Puligandla navigates queer coming-of-age stories in spades. In her anticipated debut novel, Zigzags, out this month from Not a Cult press, readers are let into a fictionalized version of her own. The aptly titled book is framed by an expansive queer lens; it follows graduate student Aneesha through her return to Chicago for the summer, where she writes and carouses with friends-as-chosen-family, weaving and bobbing through a haze of messy longing for an old flame named Whitney.

I spoke with Kamala about her literary approach to the friendships in Zigzags, and our own.

———

EMILY WELLS: We can skip right over the platitudes about autofiction and writing from life, and focus on the aspects of your life you’re clearly most concerned with translating to the page: friendship. Aneesha is incredibly introspective, yet her character is revealed, to the reader and to herself, through those she surrounds herself with. There’s a moment early on, after Richard makes an observation about Aneesha that had not occurred to her, when she wonders what more he knows about her life that she doesn’t—and as I reader, I wondered, too! Can you talk a bit about building a character through the points of refraction of other characters?

KAMALA PULIGANDLA: I’m very happy to skip over the platitudes with you, Emily, thank you for that. As you know, friendships have been the most important and transformative relationships in my life, and so I don’t think it’s surprising that they’re also the tool that I’m using to reveal Aneesha both to readers and to herself. Part of this is about her being a writer and part of it is about her being a person in her mid-twenties, who needs help to see who she is. I think this method of discovering who you are and what you want by looking at the people you’ve chosen to put into your life is a very writerly way to be reading people. Aneesha presumes that everyone’s choices and feelings are linked together by thematic undercurrents that can be tied into a cohesive narrative. Which is something that I, as a writer do with my life. That’s quite literally how this book came about, and while I know now that this intentional linking of events is the difference between fiction and a real, complete life, when I was 24 and couldn’t see how all of my pieces were adding up, it felt important to have people to compare myself not quite with, but against, to start giving a shape to who I was.

So when I was building this narrative, it felt important that every character bring out something slightly different about Aneesha. Richard is probably the most valuable in showing her who she is and also who she is not. I remember early on people telling me there were just too many characters in this book, and I was determined to keep them. Not only because that’s how I live my life, but because, in the end, figuring how to carry all of these distinct refractions at once is what the story is about.

WELLS: This is why we refer to you as “friend-hot.” Aneesha’s character and the structure of the novel are both built through these refractions. There are friends that are already established as chosen family, the all-consuming intensity of a new friendship that is akin to love, and the more demanding friendships that nudge Aneesha toward “not just hoping, actively trying,” as she puts it, toward a more permanent romance. How does this desire for endurance play out through the different intimacies?

PULIGANDLA: Aneesha’s desire for endurance, if not permanence, is what’s underlying so many of the choices she makes in the book, including going back to Chicago to begin with. But this definitely marks a shift in her life. She’s sort of been prepared to just lose things and move on before. Now, suddenly she’s concerned with how to recognize the relationships with potential for endurance—and how to give them room to grow—versus the short-term, circumstantial relationships that are never meaningless, but aren’t meant to stay with her forever, which are no less deep or significant because of that. Since I was a kid, there has always been this absurd expectation, especially for girls, that either your friendships are about committing to forever, or they’re not valuable. And the reality is that there are so few relationships, in general, that are truly capable of transforming over time to accommodate inevitable change and fluctuation, while still providing a level of satisfaction that both parties desire.

If we can talk about Aneesha as a refraction of me, this was the moment in my life when I began to understand that I wasn’t going to become the person I wanted to be, unless I changed who I shared my life with. I knew I needed to form the deep, enduring friendships that were not built upon me being available in every way, all the time, but on a shared commitment to valuing friendship as much as romances, to writing and art, to creating an unconventional path, to perpetually moving, to learning new kinds of relationships. I mean, I’m hoping that’s what I’ve been building since this realization.

WELLS: There’s a great moment when this comes through—Whitney says to Aneesha, “You’re my best friend. I want you to be happy.” Aneesha feels “a twinge at Whitney’s phrasing, at her removing herself from my happiness.” Building friendships that are valued as much as romances, perpetually moving, strikes me as something you are uniquely good at now. How are you feeling about that aspect of the friendship-based world-building project now?

PULIGANDLA: [Laughs] Great question! Well, I think it’s going well, but I think the reason I like this project is that when you’re really invested in it, it can’t not go well because you can always adjust! It took me a long time to find the people with whom I felt an enduring connection. I’ve always valued a strong commitment to imagination, to not living in a single reality, but being open to having multiple selves and not being alarmed by all the ways you might not know all of someone, including yourself. Those can be hard qualities to find. It’s often why I have young friends—a topic for another day—but I am pleased that I now have some reliable adults in the mix.

Now, it means that the friends who are closest to me recognize our differences and sameness, the things we’re great at and the things we’re still figuring out, and we’ve learned to balance our company in many different ways, so we can enjoy and learn from each other. Ultimately, we want to help each other keep growing and explore new avenues of ourselves, so we can continue to build a world together that we want to share — whether that’s physically in our homes and the way we care for each other, through stories we create, or conversations and events that explore a question, which then transform my relationship to something I thought I knew. The throughline in my life has been finding myself happy with what I have, and then sitting on the edge of my couch and excitedly asking myself, “What’s gonna happen next?”

WELLS: “What’s next?” is an astute summation of the driving force of the book and our friendship. I remember one of the first presents I got you was a mood ring; I wanted you to know that I cared about your mood and states of flux. Was it challenging, narrative-wise, to have Aneesha land somewhere? How do you give a character a satisfying resolution of non-resolution?

PULIGANDLA: I appreciate that you got me a mood ring. It’s also a really nicely shaped mood ring that fits my style, which I can’t say I’ve seen a whole bunch of! “What’s next?” is clearly a driving force in our lives. So I think that’s something very present in the book, even though I didn’t mean to initially make that the underlying question. Don’t you love when your work reveals to you who you are, whether you like it or not?

I think you’re right that it was hard to end this. I have a difficult time with endings, in both writing and in life, because things don’t stop playing in my head, even after they stop occurring in my life. People and places continue to live on in my mind, and I can visit them there and they have things to say and I can walk with them through a scene. But you can’t have a story if you don’t pick an ending. Because you can’t make meaning out of actions/decisions/emotions, in a significant way, if you can’t create a container in which to define their relationships to each other, to define what their consequences and hence their values are, and then present them as a snapshot within a bigger picture. And so I did have to draw the ending.

For me, satisfactory endings tend to come in several ways. There’s one where you, as a reader, finally see a character come to terms with something you’ve been waiting for them to recognize. There’s another where you, as a reader, finally understand something you’d been waiting to see more clearly. And I think there’s another kind where, as the reader, you feel a great momentum in a particular direction that feels inevitable, and it either finally hits or it near-misses. Aneesha’s ending feels like a combo of these. I decided that once she recognized the distinct changes in her relationships with all her friends and with Chicago, that she ultimately understands there has been a shift in who she is and what she wants. That felt like the place to end this book, to give weight to the relationships in it, and to leave the reader with the same excited sense of “What’s next?” that she feels, and is perhaps my signature feeling.

WELLS: That ‘resolution’ or ‘closure’ can be something of a fantasy comes through really well. It brought to mind José Muñoz’s essay “Queerness as Horizon,” which argues for a queer future that is hopeful and has momentum, but holds the past close. He was perhaps speaking more structurally, but I wonder if a similar dichotomy allows the novel to create such a vivid, queer-centered universe.

PULIGANDLA: I think this is a great essay that does really speak to the way I tend to organize narratives in my head. Thank you for throwing this down, Emily! Particularly in the sense that time takes on different meanings in different contexts. There is a passage in that essay: “More nearly it is important to call on the past, to animate it, understanding that the past has a performative nature, which is to say that instead of being static and fixed, the past does things.” That captures the difficulty I have with creating endings, because I think to put a cap on a story is to render it over and complete. It places it in this harmless zone of the past, when I know very well that no story worth telling is ever over or complete, and the past is not only behind us, it continues on, everywhere. Being alive in this country right now is a way of living in the past and yet, here I am, and in so many ways, I know I’m also a kind of future.

What I was still learning when I was living in the time that this book takes place and even in writing this book, was exactly that queer horizon. And so much of this book ended up being about how differently I was moving through my own life, with my own relationship to time, because of my youth, sure, but because I was not and am not interested in straight time. In straight culture, it seems that the future is about the diminishing of possibilities instead of their infinite expansion, which just makes no sense to me!

You mentioned the “vivid, queer-centered universe” of this book, and I actually disagree with you that the universe of this book is very queer-centered, and that’s part of what’s so troubling for Aneesha. What is queer, though, is Aneesha’s perspective. What feels so prominently queer, to me, when I re-read it, is the chafing and discomfort that Aneesha sort of just shoulders through in her everyday with a little sneer.

When I once read from this book in San Francisco, a group of my friends were like, “Well she’s obviously unhappy because she’s surrounded by white people.” And that was also part of the chafing, part of what renders Aneesha’s queerness even more prominent, what gives her a very different way of experiencing not just time, but possibility, imagination, expectations for love and success—what the past, present, and future mean to a queer person of color is very different than for those who are not. That was something that I, as a writer, especially as a fiction writer, was still learning then. And if only I had just read this essay!

WELLS: Lastly, we have to plug your novella and all the great things you’re doing at Autostraddle. Can you let readers know what you have up next?

PULIGANDLA: My novella is the next most exciting thing I want to talk about! I’m very in love with it. It still comes from very fresh parts of my heart, though it’s also a rumination on a past self. It’s called You Can Vibe Me On My FemmePhone and it’s coming out in January 2021 with Co—Conspirator Press, which is a small press that prints on a risograph, associated with the Women’s Center For Creative Work in L.A. It’s about a group of queer friends who are working toward self-improvement using a phone that purports to have a feminist operating system. It’s the kind of work that embraces queerness so wholly and earnestly, that it also manages to be a satire of it.