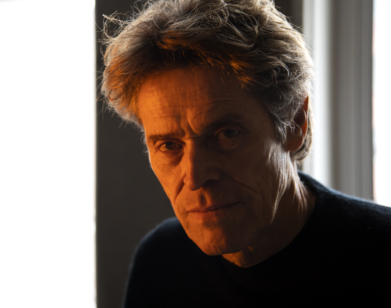

Jonathan Lethem’s private eye is set loose in our madhouse moment

Most detective stories are an attempt to make a world gone suddenly mad sane again with a clear, logical solution. Jonathan Lethem’s detective stories peel back the sheen of sanity and revel in the gonzo madness stewing just underneath. His last detective novel was the 1999 meta-masterpiece Motherless Brooklyn, set in his native borough. Now, he returns to his noir roots in his latest novel, The Feral Detective, which sends a spiraling, Trump-spooked New Yorker named Phoebe Siegler to Southern California in search of a friend’s missing daughter. Lethem is a rollercoaster writer—the joy of reading The Feral Detective is as much about riddling out any sort of whodunit as it is all of the peaks and dips and racing turns of his adventurous prose (he describes dogs barking “like angry tape loops”). The cultural madhouse nourished by Trump is a perfect universe for Lethem to let loose and explore our twisted American psyche. Having giving up New York for California, Lethem spoke with Interview‘s Christopher Bollen over the phone about crime, film, and foundational American myths.

———

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: You’re famously an admirer of detective novels. When exactly did this start?

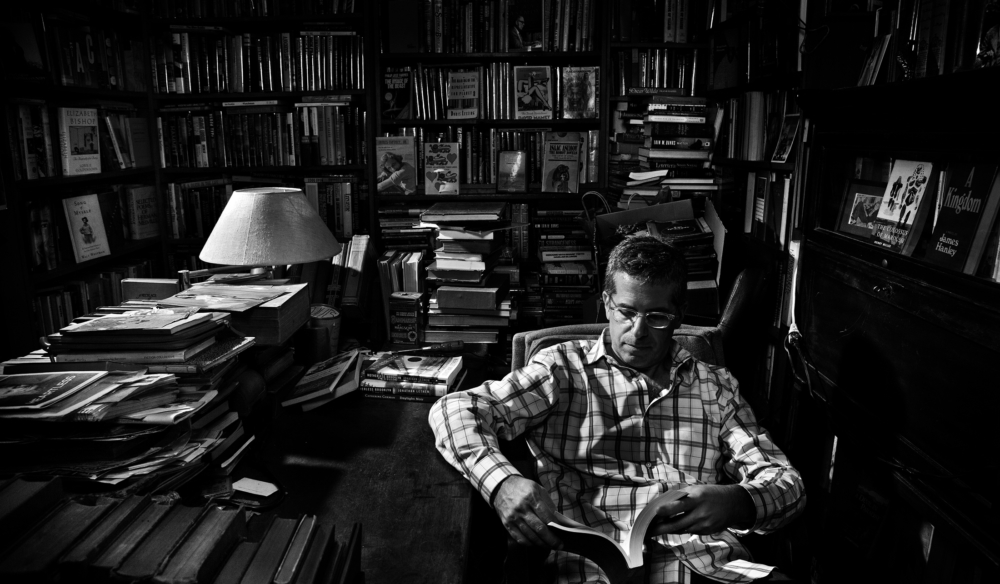

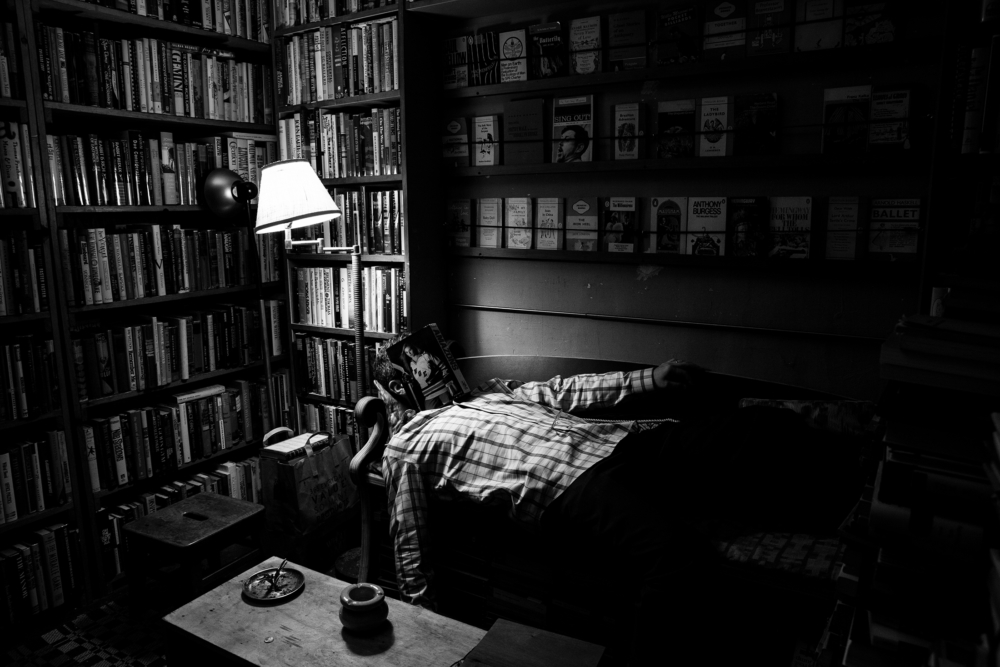

JONATHAN LETHEM: The first one was a Raymond Chandler novel from my mother’s bookshelves, Farewell, My Lovely. I’d already been reading Agatha Christie, too, at that point. Those were amusing and probably some of the first “grownup” novels I’d actually finished. But, I always preferred “crime” to “mystery” as I saw it. Stories of criminals and detectives and guilt and complicity up to, and including, Dostoyevsky and Kafka, rather than clues-and-solution. If I could substitute the word “crime” I’d be happier, in a way. What “mystery” connotes is what interests me the least: the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew aspect. I love Chandler and Hammett and their great followers: Ross Macdonald, above all, and James Crumley, and a few others. But otherwise, give me the tale of the criminal himself. Patricia Highsmith, one of my favorite writers of all. Charles Willeford, Jim Thompson, Cornell Woolrich, the black mask writers.

BOLLEN: Is it harder to write good crime stories today considering the genre has been infiltrated by television, films, and podcasts? Are there any current mysteries (in any digestible form) that you like? How important are twists for you?

LETHEM: I don’t really see any quarantine between forms. I don’t watch as much television or listen to as many podcasts as some do, but I love film, and it happily infiltrates my writing. I think writing and film are usually the better for their lively, rivalrous interplay, so I don’t worry about it. I do love reading Megan Abbott novels, lately, and Steph Cha is terrific, too. As for twists, I prefer them to olives.

BOLLEN: The election of Trump spurs your narrator Phoebe’s move across the country in search of a friend’s lost daughter. Nothing that she experiences follows expectations. Did you see the fact-free lunacy of our president as a license to let the world inside your novel go a bit mad?

LETHEM: It’s just the desert and the myth of the frontier. The whole utopian dream and experiment that is America. As William Carlos Williams said, “The pure products of America go crazy.” This predates Trump by a wide margin.

BOLLEN: How did you devise the personality and character of the title’s Feral Detective, Charles Heist? I’m asking not only when you decided that he’d have an opossum in his office, but that he’d be a desert-dwelling love interest for Phoebe?

LETHEM: Heist was developed out of a fascination with the notion of “feral children,” a curiosity that goes back to my childhood loves of Tarzan and Mowgli from The Jungle Book. Later, that image darkened when I learned about Kaspar Hauser, the famous wild child of Avignon, and other unsettling stories of what gets called a “feral child.” After I’d conceived the notion that gives the book its title—a grown-up feral child, turned detective—I wondered what it meant, and what it was for. Who would he be, and what would he care about? And that, in turn, connected to my growing fascination with this place: the Inland Empire, on the verge of the Mojave Desert. I began to see him as an enigmatic figure, a sort of refusenik—he’d been elected King of the Bears, but declined the position. Instead, he lurks on the periphery, pulling others out of the maelstrom.

“In fiction, a twist every 17 pages is my formula. If you circle them all and send the book back to me, I’ll give you a prize.” —Jonathan Lethem

BOLLEN: In the book, your California desert has bad cell phone reception. How do you tend to approach the overriding technology/cell phone conundrum for your characters? Do you feel the liberty to shut their phones off?

LETHEM: It bedevils me, really, and I keep finding sleight-of-hand ways out of the problem: bad reception, apocalypse, indifference. In [Lethem’s 2009 book] Chronic City, I wanted to write about the incursion of “the screen interface” into daily life, but I did it from the point of view of a bunch of Luddite fools for whom even eBay is a kind of overwhelming virtual reality. Even the depiction of email, to me, feels tinny in fiction. I’ve seen others get away with it. I guess I don’t have any principle at stake here, or general admonition for other practitioners. It’s just a problem I solve one book at a time.

BOLLEN: As a well-known archetypal New York writer, how has moving to California changed you? Has it changed your work in any noticeable ways?

LETHEM: I first ran away from New York to Berkeley, California, at age 19. Ever since, I’ve felt like a kind of split personality. People forget that my first three-and-a-half books were set in some version or another of “the west.” They forget for good reason: my New York books are more famous, and I’m very proud of them. But I also relate to the west as a myth very strongly—even if it’s a love-hate strength, a powerful ambivalence. Now that I’ve been living in the Southland for nearly a decade, I’m better able to consider it as a real place—albeit one shaped, both from the inside and the outside, by the myth.

BOLLEN: The west is a mythical place of freedom, at least that’s what it represents for those of us stuck back in the east. At the heart of The Feral Detective, there seems to be an attempt at freedom—coming unglued from civilization, hiding your tracks, starting again, losing track of the president and his politics. Do you think any of us can ever really get free?

LETHEM: Well, it’s the problem of utopia, isn’t it? You bring yourself with you when you go there. Your baggage travels, too. That’s the great American story: setting out into the territory, the wide-open promise of freedom and reproducing the old hierarchies, the old anxieties and prejudices, the old self-destructive urges, in a violent new conjunction, and, in many ways, worse, without the modulating anchor of old institutions and rituals. The reenactment of a discarded social order is often starker and crazier out here in the great wide open. Dystopia stalks utopia everywhere it goes.

BOLLEN: Do you think you’d make a good private eye?

LETHEM: No, I’d be hopeless. I think of all my best lines two weeks later, which is why I’m a writer. A detective needs repartee that’s ready on a much quicker basis.

Photography by Mike Vorrasi