John C. McGinley’s ABCs

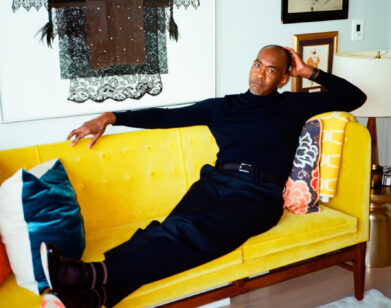

ABOVE: JOHN C. MCGINLEY. PHOTO COURTESY OF RUSSELL BAER.

“First prize is a Cadillac El Dorado… Second prize is a set of steak knives. Third prize is you’re fired,” reads the tagline of David Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross.

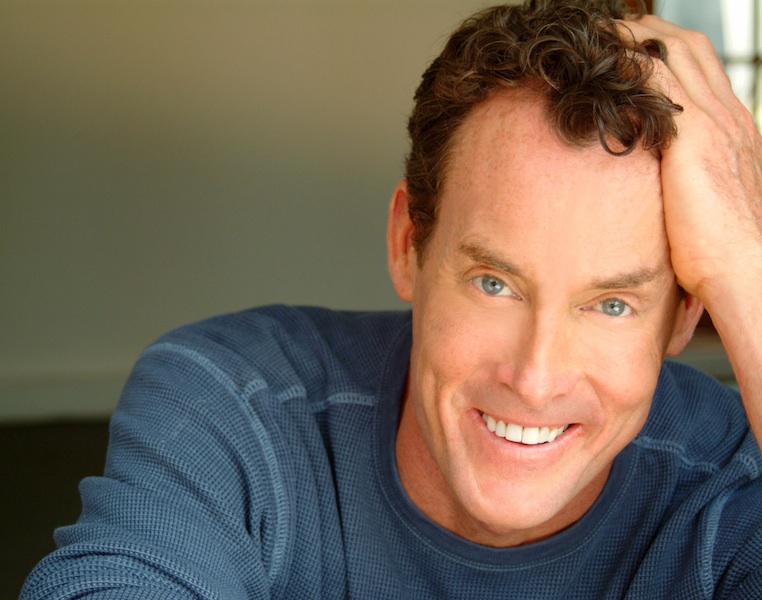

John C. McGinley seems a perfect fit for David Mamet’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play, Glengarry Glen Ross. Over the past 25-odd years, McGinley has quietly established himself as skilled character actor, specializing in hard-edged, fast-talking, and quick-witted alpha males. His talent lies in finding the possibility of pathos in his characters; for nine years, McGinley played Dr. Cox on Scrubs, turning the show’s most sarcastic character into its most compassionate. He is a frequent collaborator of Oliver Stone’s: McGinley’s first major role was as Sgt. O’Neill in Platoon (1986), and he has appeared in six Stone films to date.

Next week, the latest revival of Glengarry Glen Ross opens on Broadway, starring Al Pacino, Bobby Cannavale, and McGinley as Dave Moss. Daniel Sullivan, who directed Pacino in The Merchant of Venice, is the director. Like all Mamet plays, Glengarry is quick, coarse, funny, and brutal; its power relies on the ability of actors to make audiences feel uncomfortable. It’s a tough play to revive, if only because it has been performed with great acclaim so many times. In 2005, Liev Schreiber and Alan Alda starred in a Broadway production directed by Joe Mantello; and Pacino himself received an Oscar nomination for his role as Ricky Roma in the 1992 film version. (Pacino is not reprising the role of Roma, but playing the older Shelley Levine.)

We called McGinley earlier this week to discuss taking on such a famous role in Glengarry, cowboys on the moon, and the brutality of Broadway.

EMMA BROWN: How do you make such a famous role your own?

JOHN C. MCGINLEY: Well, because the writing is so meticulous, the work on it has to be so surgical. To try and do anything on it other than bring the qualities, the value structures, and the quirks, and the understanding of the material—if that’s not intensely personal, you’re dead meat. I think that when the approach reflects that kind of work, then it becomes your own, it has to become your own. You can’t help it.

I don’t think there’s any value in judging David Moss, except to appreciate his desperation and his hopelessness, and that those two conditions are challenges to compel people to do extraordinary things. I think we can rationalize a lot of things when we’re in that bad of shape, like David Moss is. And all actors have been hopeless and all actors have been desperate. So, to take an understanding of those conditions and really tear into them is the stuff that will yield dividends in the development of the character.

BROWN: How did you get involved?

MCGINLEY: They called me up at the beginning of August. My agent called me and told me, “You’ve got an offer to go do Glengarry on Broadway with Al Pacino and Daniel Sullivan directing.” I though it was Ashton Kutcher punking me or something. That’s the stuff dreams are made of. That was the entry point. Then as soon as I could organize my family coming East with me, which took a while, I said “Yes.” The offer was for Dave Moss.

BROWN: You mentioned that you worked with Al for five months on Oliver Stone’s Any Given Sunday (1999). Had you kept in touch?

MCGINLEY: Yeah. Every now and then we’d see each other on the West Coast. We both have children that are relatively the same age so we’ve intersected as fathers at various times.

BROWN: Ed Harris played Dave Moss in the film; does it seem like his role because of that? What was your first experience with Glengarry?

MCGINLEY: No. Look, I hero-worship Ed, but I saw the original production of this two nights in a row, and I’ve seen Glengarry across the planet. Everyone has their own flavor that they bring to the play, because the play is so stunning, it can support all of these different approaches to these different roles of Shelley “The Machine” Levine is very different from Jack Lemmon’s [in the film version]. They’re both stunning, but they’re both very different. That’s what mine will be.

BROWN: I was reading lots of articles about Glengarry’s return to Broadway. Many of them described it as a “darkly comedic” play, but it’s also just so heartbreaking…

MCGINLEY: Yeah, but it’s playing funny until the heartbreak. Right until the heartbreak the material is supported by laughs. The end is absolutely devastating…

BROWN: I heard that this is your first time on Broadway since 1985—how has it changed?

MCGINLEY: Well, this is very different—being in this show—because the run, though it’s not guaranteed, it’s sold out. Last time we came to town, it was a more traditional, you put the show up and you hope it gets good reviews and you hope people come. But, this thing is sold out, we’re going to be here for a couple of months whether you like it or not, because those seats are already filled. That’s a very, very different way to come to Broadway. The last time I was here we opened on a Friday night and closed on Sunday.

BROWN: Really? That Sunday?

MCGINLEY: Yeah, absolutely. We had no money. You get a bed for two nights. That was back when Frank Rich was running the New York Times’ [theater reviews], and whatever he said was the word. He gave us a bad review, and the producers, they closed us on Sunday.

BROWN: How long was your rehearsal process for that play?

MCGINLEY: We were three months out of town. So, a month in Dallas, a month in Palm Beach, and a month in Fort Lauderdale. Then we brought the show to town and it was tight as a drum and it got a bad review and it was devastating.

BROWN: Yeah, that must have been so disappointing. I can’t even imagine.

MCGINLEY: I can’t either, it was absolutely devastating.

BROWN: Had that happened to you before?

MCGINLEY: No, that’s the one. The only one I needed. You don’t want it to happen many times. That makes your skin a little tougher.

BROWN: How have your first previews of Glengarry been going?

MCGINLEY: Great, it’s a real privilege and a treat to be able to do it at night and then come in the next day at noon and go over stuff and tighten it and tweak it—see if you can’t fix this a little bit, or if the blocking might be better over here. That is a real luxury, instead of just doing it every night and wishing you could fix it.

BROWN: Are you not able to tweak things from night to night when the play is officially opened?

MCGINLEY: Well, the big thing is then the producers would have to pay you and no producer is going to pay for rehearsal after previews. [During the preview process] you have six hours of rehearsal a day written into your contract.

BROWN: Have there been any mishaps on stage so far?

MCGINLEY: Just the normal stuff—spilling drinks and props falling—but that’s it. That stuff, if it doesn’t happen, then you’re in trouble. Actors have to drop props and spill their drinks.

BROWN: Do you feel like a play is better by the end of the run?

MCGINLEY: I don’t know, that’s a really good question, but I don’t know. I did Talk Radio down at the Public for about a year and a half, and it was definitely better at the beginning of the run, but a year and a half is a long time. [Glengarry] is such a short run, and each night is such a burst that I can’t imagine it won’t be anything but more thrilling as we go.

BROWN: When’s the last time you forgot your lines?

MCGINLEY: I don’t forget lines.

BROWN: Do you go over them each night?

MCGINLEY: Oh, every minute of every day they’re rattling around up there. I’m saying them in my head while I’m talking to you.

BROWN: Do you have a favorite bit of David Moss dialogue?

MCGINLEY: Yeah, when I come out in the second act and Bobby Cannavale [who plays Ricky Roma] asks if the cop was rough on me, and I say, “The cop couldn’t find his dick with two hands and a map.”

BROWN: Do you have a favorite Mamet play other than Glengarry?

MCGINLEY: No, Glengarry is hands-down my favorite.

BROWN: He can be quite a polarizing author…

MCGINLEY: Yes, no question. I think he revels in that.

BROWN: Your children are quite young.

MCGINLEY: Yes, well, Max is 15, and then Billie Grace is four and Kate is two.

BROWN: Mamet is not particularly child-friendly; are your children desperate to see your play?

MCGINLEY: No. They were over at the theater Wednesday when all of the parks were closed and when the theater was empty. They got to roam and around and play in the seats, that’s all they want to do. They want to go up on the balcony, that’s more fun.

BROWN: Has being a father to young children affected the roles you would want to accept at all?

MCGINLEY: No, no, that doesn’t affect it. I’ve been in plenty of hardcore R-rated movies, they’re not seeing it until they’re adults, but it is what it is. They shouldn’t Oliver [Stones]’s movie until they’re older, and then when they’re older, they’ll see them and they’ll appreciate it. But no, that has little impact on where I fit into the storytelling process.

BROWN: How do you feel when somebody describes you as a “character actor”—is it a compliment?

MCGINLEY: I assume it’s a badge of honor. Look, to make a living as an actor, and not to have had a second job since I got out of school—call it whatever you want, I don’t care. The idea for actors is to make a living telling stories, so if you can do that, then you’re way ahead of the game.

BROWN: With some actors, you get the feeling that they want to be able to inhabit all sorts of different roles—variety is the most important thing. What do you look for in a role? What is your goal?

MCGINLEY: I read the script, I see if I like it [and] whether or not I can integrate myself into whatever story is being told. If I read it and I don’t see myself fitting in, then I have no interest. Fitting in means whether or not I can creatively fit in, if I can fit it into my life, if my family can be part of it. You know, picking up your family and moving them to New York for five months is a huge, huge undertaking. Soon as I figure out all that, then I can fit in. If I couldn’t figured it out then I wouldn’t have done it.

BROWN: When you play a character for a nine years, like Dr. Cox on Scrubs, how does your relationship to the character change?

MCGINLEY: Well, because the writers drew up a character who was so damaged, they were able to prevent him from becoming redundant. He had so many foibles and so many kinks in his armor they could just keep writing fresh stories for this guy. And I got to ride that for nine years without ever becoming kind of an exercise in redundancy, which is obviously the trap of playing a character for nine years, you could just become a paper cutout of the guy. Dr. Cox was just so messed-up and just a collection of idiocentric eccentricities.

BROWN: Do you remember the first role you ever had?

MCGINLEY: In plays, movies, or TV?

BROWN: Grade-school plays.

MCGINLEY: Yeah, in fourth grade, there was a play called Roundup On The Moon. It was like this cowboy moon musical—the fourth grade at the Glenwood School in Millburn, New Jersey. Some musical for kids about some cowboy roundup on the moon, that’s all I remember. I played a cowboy, with a lasso, up on the moon.

BROWN: One of the movies you have coming out next year is the Jackie Robinson biopic, 42. Are you a baseball fan?

MCGINLEY: I’m a baseball freak.

BROWN: What’s your team?

MCGINLEY: NY Yankees.

BROWN: Even though you live in California now?

MCGINLEY: Yeah. I mean, you can’t… what are you gonna do? I finished 42, [but] we’re still recording stuff on it. I would imagine it comes out a couple of weeks ahead of baseball season next year. It’s absolutely stunning. It’s more of a civil-rights movie than it is a baseball movie, which makes it twice as interesting. It’s about one of the seminal athletes/civil-rights persons we’ve had in this country’s history. Jackie Robinson was an astonishing, astonishing human being.

GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS OPENS NOVEMBER 11 AT THE GERALD SCHOENFELD THEATRE, 236 WEST 45TH STREET, NEW YORK, NY. FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT ITS WEBSITE.