The Painter of Modern Life

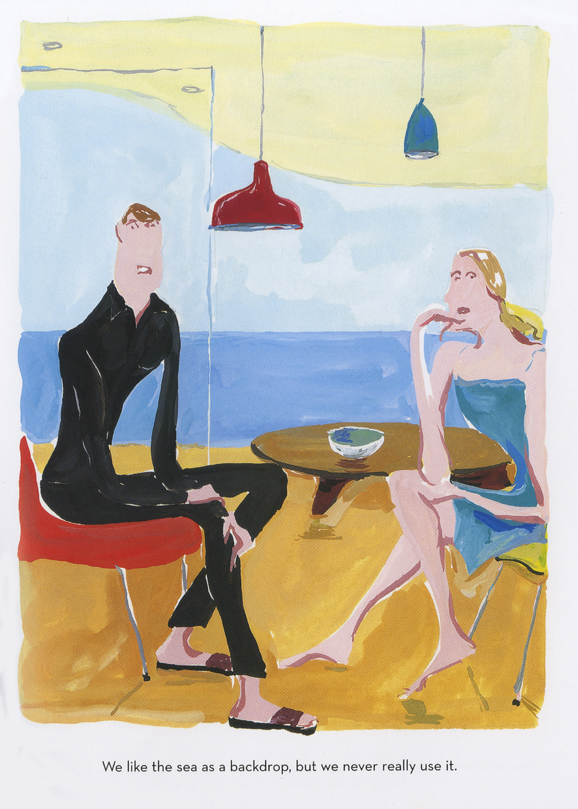

Jean-Philippe Delhomme, illustrator of Interview‘s May design portfolio, may be Western Civilization’s most literate (and/or literary) illustrator. And on Sundays he’s a painter too. And he writes novels. Altogether he is one of the most accomplished, multi-dimensional, and enjoyable satirists working this absurd planet. His new book of captioned drawings The Cultivated Life: Artistic, Literary, and Decorating Dramas (Rizzoli) was feted recently at Partners & Spade, where he showed a new series of drawings including portraits of such notorious characters as Olivier Zahm, Terry Richardson, Dash Snow, his interrogator here, and a mysterious figure known as “The Unknown Hipster,” and he signed copies his new book for many fans. It is further rumored that Mr. Delhomme will soon unveil a website, the unknownhipster.com.

GLENN O’BRIEN: Where do you find your victims?

JEAN-PHILIPPE DELHOMME: When I look for ideas, I usually end up hanging around places where I know I’m likely to spot a few characters with a bit of an attitude-outstanding looks, arrogant or funny behavior. In Paris, for example, I would do a round trip starting at Le Bon Marché, Conran, Colette, Palais de Tokyo and back to bookstore La Hune, and a stop at APC on my way back to the studio—maybe an optional stop at Le Flore, and at a few art galleries. If I return without any potential subjects, I’m in serious trouble. But most of the time, I just sit at my table, and the so-called victims happen to be inside of me, like possible selves I refrained from being!

GOB: Are any of your captions taken from real life?

JPD: I love absurd declarative statements, the way people are usually quoted in magazines or the lifestyle mantras one can read through headlines and titles. And I like to apply those declaratives statements to the situation and the characters I draw, pretending like it’s normal language. It’s a neo-Nouveau Realistes thing, pretending something is reality when using artifacts, or it’s like painting a nude from plastic mannequins (a good idea, if not already done). Then, inspiration comes from over-exposure or intoxication: After reading too much of a certain kind of magazines, or hanging too much in a milieu, my immune system reacts with captions. The thing is to not get too used to it: maybe if I camped out in an art gallery for two weeks, I wouldn’t notice the oddness of the talks any more.

GOB: How do you start to capture a personality?

JPD: Some people I see once at an opening, and I can draw them from memory back at my studio. Some others, I’ve pictures of them in magazine, and from that could get quite an accurate idea of, if not who they are, how they look for good. For example, after seeing Terry Richardson in Purple Magazine through the years, I could draw him as if we’d met a hundred times (though I would check on the latest issue for the most recent plaid shirt). It was even more immediate with Dash Snow who I only saw in two or three issues.

GOB: Have you ever done a self-portrait?

JPD: I always feared the ridiculous seriousness of the whole enterprise. There’s always the risk of the gloomy self-portrait, or the pretentious, or the falsely modest. I can’t synthesize my different appearances as easily as I can for any other subject. I would need a lot of film footage to get a better idea. Bad pictures help: by looking at them objectively you end up noticing one that one shoulder is higher than the other you’re your neck slightly bent-things that are hard to register when simply looking at yourself in a mirror.

Anyway, I had to do self-portraits, not for personal interest, but because when you’re an illustrator, people ask for your self-portrait for the contributors page. Fashion photographers are encouraged to send glorifying snapshots of them taken by a model or their assistant, showing them half-naked on a beach, or tanned and unshaved, in a remote location, or stoned in an hotel penthouse. But if I send a photo of me painting bare-chested, or mounting an elephant in India, or drinking with models at Le Montana, they’ll think it’s odd and ask more or less politely if I have a self-portrait.

GOB: What comes first, drawing or the caption?

JPD: Most of the time the caption comes first, and gives the impulse for a drawing. When the drawing comes first, it’s usually meant to remain a silent drawing.

GOB: Are you an abstract realist? How would you describe your work?

JPD: I love abstraction, emptiness, and a certain amount of flatness. But then there are all the funny details and quirks of the human figure that insist on having their share. And I like to let the process be visible-the way it was made, the brush strokes if there are brush strokes, I couldn’t do another way. But I wouldn’t add brush strokes or false drips. I’m trying to express the most of a character’s psychology, or state of mind, with the least, but I like to get all the true realistic details that most of the time remain unnoticed in real life (something which I like so much in Tom Wolfe’s 60’s pieces).

GOB: Who are your favorite painters?

JPD: When I was a student, the revelation came from a David Hockney exhibition of stage designs and costumes in a gallery in Paris. Every time I come across a Hockney, especially early ones or the more recent portraits, it makes me want to paint or draw immediately and try out new things. Same with some Manet. I rescently bought a book of Lucian Freud’s drawings and was completely fascinated by them, by the intensity, the accuracy, and the subjects. There’s a drawing of a dead monkey, and somewhere else, a portrait of his first wife that are the most exciting drawings I ever saw. And I love Dubuffet (much also for his writing). A Dubuffet always makes me smile. And of course, there is the great Alex Katz. But I looked a lot at photographers, as much as at painters, Bailey, Weegee, Walker Evans, and among them, photographers who were closed to painting: like the Joel Meyerowitz of “Flowers”, or Saul Leiter, or more than all Bruce Davidson for the “Subway” series. “Subway” was the most exciting book, bringing together Walker Evans, Basquiat, Jackson Pollock, Futura, and hip-hop.

GOB: What’s your idea of glamour?

JPD: I thought for a longtime that fashion shoots were where glamour was, until I realized that a lot of the models who look like sensitive, intellectual princess on ads and fashion stories, speak and behave, most of the time like true hooligans. Maybe glamour only exists in Proust’s salon, Guermantes.

GOB: What amazes you?

JPD: People who survived ups and downs of fame, and went on doing their own things, all the way. But also, how fast small underground trends become mass market. The sheer number of people bearing tattoos. I also wonder why people prefer to have a flying dragon or a skull or some cheap verses poorly executed on them instead of a big brand logo.

GOB: What world would you like to penetrate?

JPD: I’ve never really been part of a specific world. I’ve done little excursions into several. I wish the fashion people, or the art world, or the literary world, or the design world would adopt me so I could settle down, but I still have to figure out what would be interesting next. So, may be the cinema, or the music world. Why not the world of great chefs? Maybe I’ll go in an ashram for a silence workshop in India, and then be just happy to penetrate the world of ordinary people.

Jean-Philippe Delhomme’s most recent work is currently on view at Partners & Spade, located at 40 Great Jones Street, New York.