James Salter

I DON’T FEAR DEATH. I’M NOT OBSESSED WITH IT THE WAY EVERYBODY ELSE SEEMS TO BE.James Salter

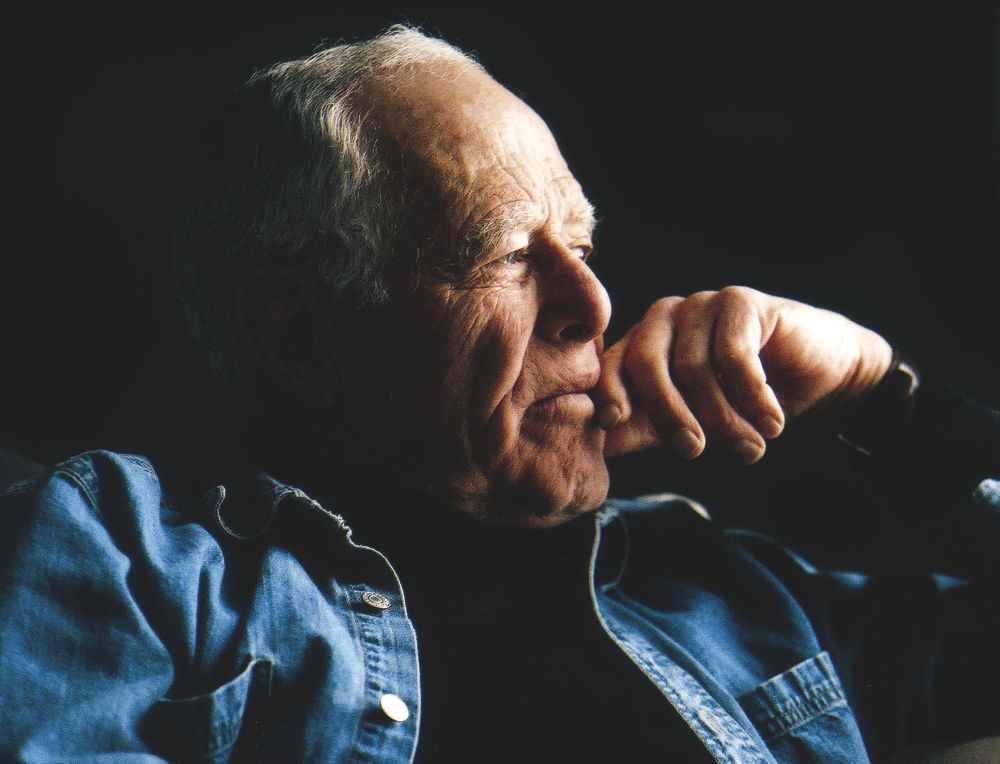

Picking my way through the snow and slush of James Salter’s driveway in Aspen this past February, I was both excited and apprehensive. A legendary, if relatively little-known, writer, Salter is the author of the 1967 erotic masterpiece A Sport and a Pastime, about a Yale dropout’s love affair in France; the virtually perfect novels Light Years (1975), a portrait of a family’s dissolution, and Solo Faces (1979), about mountain climbing; as well as some of the finest short stories of the last century. Yet his literary persona is rather magisterial, characterized by a fine, somewhat chilly polish. He’s too often been accorded the dubious distinction of a “writer’s writer.” In truth, he’s the great American writer that most of America doesn’t know it has produced.

I was in Aspen to talk with Salter about his sixth and most recent novel, All That Is (Knopf), the sweeping story of a book editor’s experiences in love and war in the 1940s. In addition to writing, Salter’s personal story is filled with distinctions: His New York City boyhood in the 1920s and ’30s as the son of a real estate man; his years as a cadet at West Point and later as a fighter pilot in Korea; and even his Hollywood period in which he worked with Robert Redford (perhaps most notably as the screenwriter for the 1969 film Downhill Racer). There was much to discuss in Salter’s A-frame mountain retreat before my return flight back to New York later that afternoon. There are very few writers I would fly across the country to meet. Above them all is Salter. There is something about his prose, which blends lushness and classical restraint in the service of a wise, epicurean view of life, that calls me back to it. I have reread Salter more often than any other living author and have memorized lines and passages by dint of sheer repetition. Also, in an era characterized by sex writing that defaults to irony and comic dysfunction, Salter restores that erotic experience to a kind of exalted, tantric level throughout his books (including this new one) that is simply hot.

When Salter opened the front door and welcomed me into a cozy, book-lined living room, I found the author less bearish than photos lead one to expect. At 87, he is trim and has close-cropped curly white hair and a lively, handsome face. He offered me a drink and mentioned that his wife, the playwright Kay Eldredge, was away for the day. Behind him on the shelves, I noticed volumes of early-20th-century Russian writer Isaac Babel, one of Salter’s favorites and, like him, a soldier-writer.

Salter proved warm and solicitous. At dusk, he threw on a stylish down coat and showed me around the mountainous area he has in lived for part of the year since 1959, when the streets were unpaved and he bought his house for a song. Now the shops that once sold climbing gear have Fendi bags in the windows. Salter pointed out a bar that, during the town’s heyday in the ’70s, would be packed with upward of 100 skiers who had glided from the slopes right up to the bar door. “There were five gorgeous women who were always there back then,” he says wistfully, “real standouts.”

THAD ZIOLKOWSKI: First of all, congratulations on the publication of All That Is.

JAMES SALTER: Thank you, thank you.

ZIOLKOWSKI: What do you think is the relationship of this new novel to your other books?

SALTER: I’d say the biggest relationship is the repetition of certain themes. I don’t want to say “topics,” but certain points of interest.

ZIOLKOWSKI: Well, the protagonist, Philip Bowman, was born the same year as you were, 1925, and, like you, in New Jersey.

SALTER: He was born in 1925?

ZIOLKOWSKI: Yes.

SALTER: Ah . . . Well, this will certainly lead people to think it’s autobiographical.

ZIOLKOWSKI: Then there’s the military experience. One of the remarkable things about your life is the long period up until you were in your early thirties when you were an officer in the Air Force. Before that you were a cadet at West Point, where you were miserable for much of the time due to the hazing and general harshness of the regimentation. Why did you stay the course there when you could have gone on to Stanford—or was it MIT? I’ve heard you considered both.

SALTER: I’d been admitted to Stanford, but my father was not a literary man or a man with aesthetic tastes to any degree. And he’d gone to MIT as a postgraduate, and he said, “That’s a wonderful school. You should go up there.” I’d never even been to Boston. So I did go up there, and you know the way kids choose schools: by the smell of it, so to speak, and by somebody they happen to see on the campus. I said, “Okay, that seems fine, but I’d like to go to Stanford.” So I applied for it. In those days, from an Eastern prep school—Horace Mann was a good school—you could get into these colleges without much difficulty. I didn’t have a precise idea of my path, but I’d say if anything, it was toward more of a literary or liberal arts education.

ZIOLKOWSKI: But then you ended up at an improbable third alternative, West Point, and you had this utterly rude awakening there. Having discovered how brutal it was, what kept you from dropping out?

SALTER: I didn’t have the nerve. My father was not tyrannical, but it would’ve been a huge disappointment to him. He had gone there, as you know, and he had a reputation. And I just felt I couldn’t.

ZIOLKOWSKI: You did manage to graduate just as World War II was ending.

SALTER: Well, I got with the program. And having had such a poor first year, and having rebelled against it so much, naturally when I turned, I turned completely the other way.

ZIOLKOWSKI: Do you have regrets about getting a military education?

SALTER: Yes, I regret it. Yes.

ZIOLKOWSKI: The narrowness of it.

SALTER: Its narrowness, exactly, and various other aspects that you cannot rid yourself of really.

ZIOLKOWSKI: For instance?

SALTER: Oh, moral notions—notions of honor. Things that may even be out of step with contemporary life.

ZIOLKOWSKI: A kind of puritanism?

SALTER: West Pointers tend to be rigorously honest—more than necessary, in my view. Habits that you form there, that you’re made to form there, are very difficult to get rid of. I hate a messy room, for instance. And I like things to be in twos—I mean, where’s the other sock? I’m unwilling, in small things, to just say, “Oh, to hell with it!” I think that comes from those years and the insistence to “do it right, make it right.”

ZIOLKOWSKI: Was it the love of flying that kept you in the military as a career officer in the Air Force?

SALTER: I can’t really answer that specifically, because I don’t know what I would have done. I was into flying before I graduated. So I graduated as a flyer.

ZIOLKOWSKI: You were waging warfare as a pilot. You went out looking for the enemy over Korea. That habit of seeking out the danger, of seeking out the enemy—what happened to that when you were no longer a fighter pilot?

SALTER: I was still a fighter pilot. You consider yourself one for a long time. But fighter pilots don’t necessarily have to be aggressive personalities: cocky and daredevil, there are those kinds too. The best ones, in fact, are somewhat measured, often quiet and very capable. Aggressive, yes, but not in personality. Aggressive in spirit, not in act.

ZIOLKOWSKI: Not brawlers in a bar.

SALTER: No, nothing like that.

ZIOLKOWSKI: Some of the most breathtaking passages in your work concern aerial battle. I often put them on the board for my students and we pore over them in amazement. One of my favorites from your memoir, Burning the Days, is the description of a plane you shot down. The pilot has ejected, and you watch as “the MIG, now a funeral craft that bore nothing, was falling from thirty thousand feet, spinning leisurely in its descent until its shadow unexpectedly appeared on the hills and slowly moved to join it in a burst of flame.” But some of the beauty in your war writing has to do with the fragility of memory and the way the faces of your comrades are as in a dream, and they’re fading. Yet, I know from having written a memoir myself that people from the past tend to get in touch with you. I was wondering whether any of those aces from your squadron actually said, “You know, I read your book. I’m still alive and well. How are you? Let’s get together.”

SALTER: If they read it.

ZIOLKOWSKI: Did you hear from any of them?

SALTER: Oh, some of them, of course. Somebody called me this morning, as a matter of fact.

ZIOLKOWSKI: Having read Burning the Days [1997]?

SALTER: He wasn’t in the squadron with me, but an Air Force classmate of mine, with whom I’ve never been in touch . . . I mean, I knew who he was, but he called out of the blue.

ZIOLKOWSKI: What did he have to say?

SALTER: He said, “I loved your book. I’ve read it three times and I just wanted to call you and tell you that.”

ZIOLKOWSKI: That’s gratifying.

SALTER: He’s a rare one, believe me. [laughs] I don’t want to malign them. They’re all literate, completely literate, but generally speaking, I’d say that they read a different kind of book—biographies, histories.

ZIOLKOWSKI: When you were flying those missions, did you ever take notes and think, I’m going to write about this? Or were you utterly in the moment and consumed by it?

SALTER: No. I thought, I’m probably not gonna get through this! [Ziolkowski laughs] But I was keeping a very rudimentary journal. I wanted to keep track of the missions, and generally of what I felt and saw, and what other people did. I knew I was going to forget all that. I mean, sometimes you flew two, occasionally three missions in a day. By the time you’re flying the third one, details of the first have already been mixed in. So I did keep a journal. And I thought, “Well, if anything happens to me, somebody will take that notebook. They’ll send it home.”

ZIOLKOWSKI: Do you keep a journal now?

SALTER: I used to, but I’ve become a bum.

ZIOLKOWSKI: There’s that great line in Burning the Days about a fellow West Pointer who died in World War II: “His death was one of many and sped away quickly, like an oar swirl.” In your work, a death can happen suddenly and be dispatched with, which gives it a paradoxical kind of poignancy.

SALTER: I don’t fear death. I’m not obsessed with it the way everybody else seems to be. It’s wrong to say “everybody,” but in literature I see it all the time—preoccupation with it, philosophical preoccupation, in fact. That’s a principle element of literature and philosophy, often cited as the main element, the only real element. I say give it up.

ZIOLKOWSKI: Another theme that recurs in your work is that of what you call “the upper world.” It often has a European context—the traditional aristocracy of England or the continent.

SALTER: In the Air Force, I was stationed in Europe for four years, and that was an awakening.

ZIOLKOWSKI: You were in Germany and France?

SALTER: Yes. I didn’t know about Henry Miller then. His books weren’t even available in the States. But I was eager to see Paris—and France, for that matter. And, of course, we’d been fighting Germany for three years. So to go over there was immediately to see these places in reality. It made a big impression. And one thing you see very quickly, in France particularly, but in Germany as well, everywhere you go, is the waterline of culture. The culture and the aesthetic seem to be higher—you notice that immediately. Then as I got to know the life a little bit, I found it even more attractive. Not to the extent of wanting to live in Europe, but of wanting to eat it. I wanted to take a big bite out of it.

ZIOLKOWSKI: You depict the world of the aristocracy, loosely defined, as desirable and admirable. I’m thinking of Burning the Days, but there’s a tendency in all your books to ground the narrative in elites of one sort or another—elite fighter pilots, American blue bloods in A Sport and a Pastime, the semi-bohemian lifestyle elites in Light Years. For me, as an American reader, with an American’s traditional hostility to the notion of an aristocracy, I’m always a bit conflicted by this in your work, as well as seduced by the way you present the whole thing, the appeal of the sumptuous, the richness, and a kind of structure of sexual secrecy—their great privacy. As if those great estates were made, above all, for pleasure and for doing as one likes. In All That Is, London is “the hidden luxury from imperial days with its guardians in the form of silver-trimmed doormen at the great hotels.”

SALTER: Sumptuous and rich implies a certain leisure and perhaps laxity. I don’t mean that—I meant the rigor of the culture. All the bridges, the roads, the buildings, the attention to details in daily life that I suppose you could find if you went to Milwaukee, to German families, or to wherever the French are in America—maybe Louisiana . . . But in general, American life is more easy-going than that. And civic pride, national pride in a cultural sense, isn’t as great in America. I think what they esteem in America is character and energy, and being different and superior to other peoples. Of course, every nation feels itself to be superior, but in America it’s a jaunty feeling, and in some cases a rather ominous one among the super-patriots.

ZIOLKOWSKI: In your new novel, that superiority and style comes up first in the form of the Virginian elite, which is the world the first wife of Philip Bowman comes from. It’s a world of foxhunts and drinking and horses, and the marriage doesn’t last long, but Bowman is fascinated by their self-assurance and insularity.

SALTER: I like aristocracy. I like the beauty of aristocracy. I like the hierarchical feeling. You could, if you want to be mean about it, claim that it’s due to my military experience. But it came before that. I love their freedom of behavior. They’re not constrained by these penal attitudes, these puritanical attitudes about behavior, both socially and morally. I don’t mean they’re immoral, but they have a freedom that I admire. An unquestioned freedom. And odious things happen, which they admit to openly—I envy that.

ZIOLKOWSKI: The epigraph to All That Is is “There comes a time when you realize that everything is a dream, and only those things preserved in writing have any possibility of being real.” Which brings to mind the long years you spent as a screenplay writer in the film world. Did you hold the same conviction about the superiority of the written word when you were involved in the making of films?

SALTER: Oh, yeah. I’ve believed that from the beginning but was not able to express it, I suppose.

ZIOLKOWSKI: When you fell in love with film in the early ’60s, it was the New Wave moment. In Burning the Days, you remember Lincoln Center and its huge screen and the feeling of being in the presence of art.

SALTER: I wrote a script in New York because I was asked to do it. I’d never written one before. Was that after I’d seen the New York Film Festival in 1963? I don’t remember precisely. It’s about the same time. It’s a time when you’re going to the movies frequently, when you’re talking to people about them, when you’re talking about films that not everybody has seen, perhaps, so there’s a certain, I don’t want to say superiority, but you’re somewhat elevated in your feelings about them. And, of course, they’re glamorous. You must remember also, I was trying to earn a living. I thought, This is a possibility. So I wrote that first script; that was the one that Redford happened to read.

ZIOLKOWSKI: Goodbye, Bear. Redford was a stage actor at that point.

SALTER: Right, he was in the play Barefoot in the Park. Perhaps Jane Fonda was in it with him? Or maybe she was in the movie.

ZIOLKOWSKI: In the memoir, you describe yourself and Redford as “two naïfs in the sunlit city.”

SALTER: Oh, I was naive. Well, he was naive, definitely.

ZIOLKOWSKI: With regard to the film world?

SALTER: And a lot of other things, I might add. But I felt he was more naive than I was. I’ve since changed my mind.

ZIOLKOWSKI: You wrote the screenplay that became Solo Faces in 1977, at Robert Redford’s request, but it never got made. Redford felt it wasn’t quite right for him.

SALTER: Well, lots of scripts are written and not made, even scripts that people want to make. In this case, I think Redford felt it didn’t exactly strike the right tone. He likes to play loners, outdoor figures, figures with their own moral standards. And in Solo Faces, the main character, Rand, has all of these, but it didn’t quite click. For him. But a good friend of mine had become editor in chief of Little, Brown, and he said, “This would make a wonderful novel. Will you consider doing that?” And eventually I did.

ZIOLKOWSKI: Solo Faces is a great novel. I hear it has a cult following among climbers.

SALTER: [British author] A. Alvarez, who’s a genuine climber, said that it’s the first novel, or the only novel, he’s read that has the genuine feel of climbing in it.

ZIOLKOWSKI: And that’s because you had done some [climbing] yourself. You took up climbing in your early fifties. What was that like?

SALTER: Jesus. I don’t know how I did it. I was climbing with Royal Robbins—he was then the soul, the spirit of American climbing. He was a record-setting climber. And we were climbing not far from here, up the Roaring Fork, a big granite face. We were having dinner that night and I said, “You know, Royal, when we were doing a certain part of the climb, I was just dying. I was in terrible anguish because I knew I couldn’t do it; I just knew I couldn’t do it and I had to do it anyway. Do you ever have a feeling of anguish?” And he said, “All the time.”

ZIOLKOWSKI: Your prose can have a cinematic quality. Do you think you developed a certain style from those years when you were writing screenplays?

SALTER: Not consciously. But I think everybody’s been influenced by the cinematic, the cutting, also long passages followed by silence.

ZIOLKOWSKI: That’s an interesting category, silence in writing.

SALTER: Yeah. Well, I’m sensitive about this—that I don’t write enough dialogue, that I’m not gratifying the desire for just listening to people talking. I’m inclined to write dialogue that I think needs to be there, rather than just spending time talking about this or that.

ZIOLKOWSKI: Maybe descriptive writing is the closest thing to silence in a novel.

SALTER: I’ve never thought of it that way.

ZIOLKOWSKI: For instance, in Burning the Days, there’s a description of your father’s breakdown toward the end of his life: “He was just lying down for half an hour, he said. We sat in the living room, my mother and I, crushed by finality while he lay in bed in the city he had meant to triumph in, in the afternoon, traffic blaring in the street, the tall buildings shining their dead windows, gulls sitting on the water.” That’s an example of how you deploy this technique of showing individuals surrounded by an indifferent, multidimensional world. These other microcosms don’t care about the human, but they lend the human dimension and pathos; they create a richer, more complex reality.

SALTER: Yes.

ZIOLKOWSKI: I love in your work how a few phrases create the effect of the Bruegel painting of Icarus. He’s falling, but the peasants are going along. It’s not always so poignant, but it’s an effect that is close to silence for me.

SALTER: Yeah.

ZIOLKOWSKI: A lot of All That Is takes place in New York City, where you were raised from the age of 2. Your relationship to New York as a native son is complex. On the one hand, you write in your memoir that you were “born to the city and thus free not to love it.” On the other hand, you have an authority about New York that non-native writers lack.

SALTER: I never left it. I mean, it’s always your city. And it seems completely familiar to me, even the newness of it, wherever it is. And of course the geography, the emotional geography of my life is all right there in New York. You pass certain buildings, certain corners, certain streets, and parts of your life are illuminated for a moment again. It’s like the smell of the earth to people who come from the country.

ZIOLKOWSKI: I was reading Charlotte’s Web to my son recently, and in the introduction, E.B. White is quoted as saying that the main thing he wants to convey with his writing is that he loved the world. I think of that as something that comes through in your work also. At the heart of it is a celebration of experience—as if to argue that the world and what happens in it is enough. That’s how the title All That Is strikes me, as a kind of summational claim for the adequacy or the fullness of life as it’s lived, as opposed to another world or some metaphysical longing or longing for elsewhere.

SALTER: I think it’s an astute description of a lot of what I’m doing. I mean, it’s tremendous: this world, this life. Take it while you have it.

ZIOLKOWSKI: So what’s next for you? What are you working on now?

SALTER: Are you kidding? You think there’s going to be a next? My dear fellow, let’s have lunch!

THAD ZIOLKOWSKI IS DIRECTOR OF THE WRITING PROGRAM AT NEW YORK’S PRATT INSTITUTE. HIS MOST RECENT BOOK, WICHITA, A NOVEL, CAME OUT LAST YEAR.