James Lasdun and the Construction of a Character

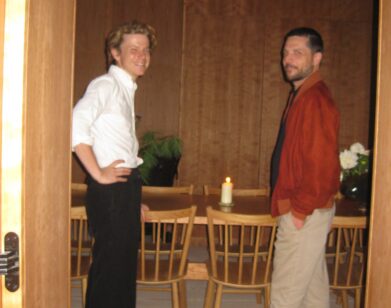

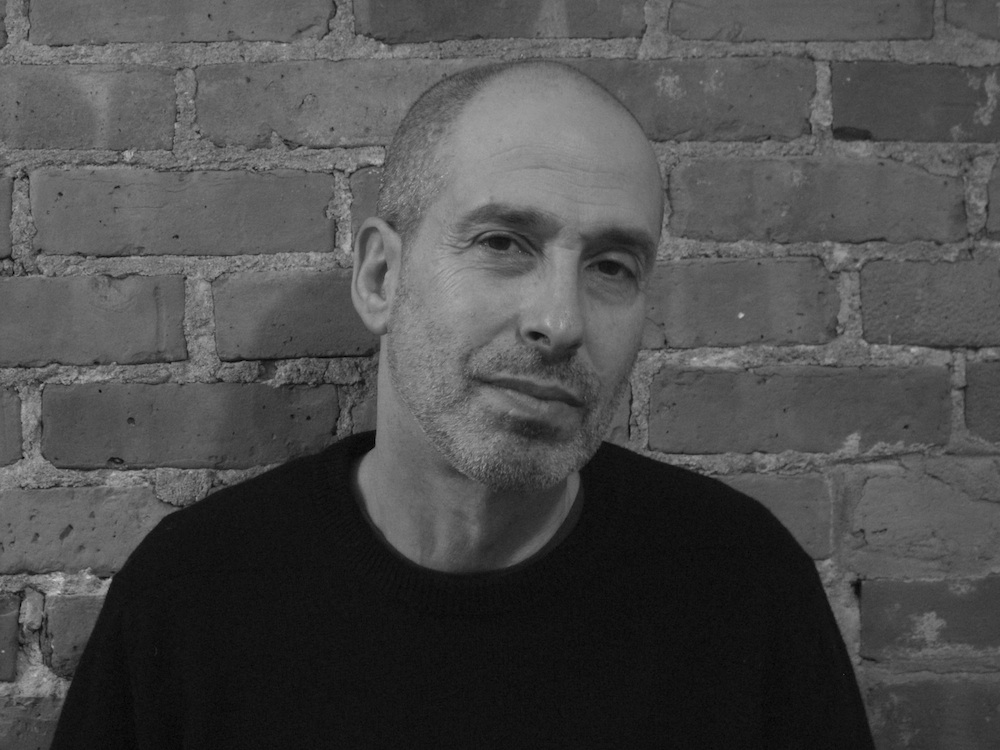

ABOVE: JAMES LASDUN. PHOTO COURTESY OF PIA DAVIS.

Ten years ago, British-born, American-based writer James Lasdun won the first BBC National Short Story Award. Titled “An Anxious Man,” the story in question is a riveting tale of a husband beset with financial woes on vacation with his wife and daughter. It possesses so many hallmarks we have since grown to love in Ladsun’s writing: impeccable language, dry humor, and an excruciating psychological tension. That same year, his second novel, Seven Lies, was long-listed for the Man Booker prize.

In Ladsun’s new novel, The Fall Guy (W. W. Norton & Company), a wealthy Wall Street banker named Charlie feels indebted to his troubled cousin Matthew for helping him out as a child in England. Charlie invites Matthew to spend a few weeks with him and his attractive wife, Chloe, in their idyllic mountaintop home in upstate New York. Of course, nothing is what it seems; moral lines are blurred and guilt, betrayal, and eroticism weave together to create a darkly compelling tapestry.

JEFF VASISHTA: One of your skills as a writer is augmenting the psychological tension by playing on the suspicions of your characters. Your short story An Anxious Man had that. It’s not an easy skill to craft that unease. How do you go about creating it?

JAMES LASDUN: Thanks! I think the suspense comes mainly out the volatile instability of the main character in each situation. Joseph in “An Anxious Man” is so entrapped in his own stock market worries that everything else in his life becomes merely an extension of the hope and dread cycling relentlessly inside him. Matthew in The Fall Guy is so determined not to acknowledge his own justified rage against his cousin, that the suppression itself becomes a kind of blind surrogate force of destruction, helplessly creating situations of increasing danger to himself and everyone around him.

VASISHTA: From reading this novel I would assume you’re something of a master chef. Are you?

LASDUN: Emphatically not. I enjoy good food and, like Matthew, I find cooking a soothing activity. But I tend to just throw things together as the mood takes me, and hope for the best, which is the opposite of Matthew’s meticulous, obsessive, and increasingly elaborate approach. I view his meals as a pretty good indicator of his darkening state of mind.

VASISHTA: You pack in so many interesting details and subplots—the Rainbows, Matthews’s dad’s disappearing act, the outspoken English dinner guests. Do you plan all this out before hand or does it come instinctively when you’re writing?

LASDUN: All I really started with was the situation of a precariously stable emotional triangle that gets totally knocked out of kilter by the appearance of a fourth figure. Also the bucolic, upstate summer setting with the heat and the pool and the cicadas. Not much pre-planning besides that—I have to actually write things out in full to know if they’re going to work, which makes for a somewhat exhausting process of trial and error. This is a short novel but it took about two years to write.

VASISHTA: Writing this must have been a challenge because on one hand, you want the reader to sympathize with the narrator, but on the other, he’s a thoroughly unlikeable person and becomes more unlikeable as the novel progresses.

LASDUN: Well, I totally disagree about that. To me sympathy for a character has little to do with how morally upstanding or wicked they are. All that really matters for me is how human and interesting they are. I happen to be drawn to characters who operate under intense internal pressure, which often comes from some deep psychological conflict, and Matthew is no exception. I liked following him in his fateful career. Obviously he’s somewhat screwed up, but I see him as someone who tries his best with the cards he’s been dealt by life, and would rather do good than harm. Not to say that he isn’t culpable, but he’s not fundamentally malicious.

VASISHTA: None of the main characters in The Fall Guy are particularly likable. They’ve all done things they shouldn’t of. It’s an interesting set up; in many novels there is one protagonist you root for.

LASDUN: I like them all. They’re not necessarily “nice” people, but they come at their problems and opportunities with, I hope, vivid energy and individuality, which makes me care about what they do and what happens to them. Maybe I’m perverse, but the question of “rooting” for a character, or setting out to write a character for whom other people will root, has never had anything to do with why I read or write fiction. As long as the writing and story remain alive, intense, invigorating, provoking, the characters can be as demonic or saintly as the author wants.

VASISHTA: Perhaps “rooting” is the wrong word, but Matthew was certainly someone, whom I felt a connection to at the beginning of the novel. A fellow struggling creative, trying to make his way his way in the world. As the story progressed and things spiraled out of control, his actions left me increasingly alarmed to a point where I felt I’d lost the connection I initially had with him. Did you agonize about the way this played out? Without giving anything away, a part of me still wanted him to get on the bus to New York.

LASDUN: Writing a murder—and a murderer—always involves more than the usual amount of agonizing, at least for me, but the hope is always to bring the reader all the way into that very extreme act—in terms of psychological understanding if not moral approval. No question, though, that it’s a major new thing to take on board about a character, and that some kind of reappraisal is going to follow. I think—hope—that the fact that you wanted him to get on that bus means that, even after reappraising Matthew, you still connect with him in some way. I agonized about the ending too; in fact wrote several version where he does get on the bus, and all the way to his dream island. Somehow it never felt quite plausible.

VASISHTA: There’s something quintessentially English about your writing, I find. There’s a dry humor, the almost overly analytical nature of the main characters, or particularly the English ones. James Woods described you as “one of the secret gardens of English writing; one discovers his delicate and blossomy prose with delighted surprise.” Do you know if your work is more appreciated in the U.K. or U.S.?

LASDUN: I do continue to think of myself as an English writer, or at least a European one, despite having lived more of my life in the States than the U.K. I studied English literature at university, so that had a strong effect on me—though translated Russian literature probably had even stronger one. And yes, I like my humor dry. But I haven’t noticed any particular difference in appreciation—or the opposite—from either side of the Atlantic. My first book was much more warmly received here than there, and in fact led directly to the teaching jobs that brought me here in the first place. On the other hand, some of my other books have done better over there…

VASISHTA: Have you ever thought about moving back to England on a full time basis or do you find being an Englishman abroad brings out a certain viewpoint and inspiration that perhaps you might not otherwise have?

LASDUN: I feel pretty settled in the States. My children have grown up completely American, so I highly doubt I’ll ever move back. America as a setting seems inexhaustibly fascinating to me, and I think there’s something about the outsider viewpoint that works for me. Being of Jewish descent in England always carried a vague sense of being foreign, while not being a practicing Jew made it hard to think of myself as fully Jewish either. So living here in a way just clarifies that terminal outsider position— makes it somehow official, which I like.

VASISHTA: Your memoir, Give Me Everything You Have, is probably every teacher’s nightmare—being stalked and trolled by a student. Did it put you off teaching?

VASISHTA: It was a nightmarish experience, but I’ve tried hard not to let it make me wary or distrustful, so I continue to teach a little, and still enjoy it. Sometimes it’s the people around me who seem more affected—I often get emails with some nervous remark from the sender assuring me they’re not stalking me!

VASISHTA: The Fall Guy seems begging to be made into a film. Which actors would feature in your ideal cast?

LASDUN: A friend in the film business suggested Tobey Maguire for Matthew, which seemed interesting. Ethan Hawke could bring out the well-meaning side of Charlie, which I think would enhance the character’s basic callousness and egotism. Rooney Mara for Chloe? She always seems to have great reservoirs of half-conscious secret motive under her innocent gestures and expressions.

THE FALL GUY COMES OUT TOMORROW, OCTOBER 18, 2016.