Irving Blum

I had a wonderful conversation with Andy. He kept asking me about movie stars and studios . . .He wanted to know everything. Andy was incredibly curious—I liked that about him.Irving Blum

If the contemporary-art scene of mid-1950s New York was small, centered mostly around a cluster of galleries on 57th Street, then its Los Angeles counterpart was miniscule by comparison. There were just a handful of galleries in L.A. at the time; few were showing new American art; and it wouldn’t be until the early-’60s that museums were a significant part of the cultural landscape. But the lack of infrastructure also meant that anything was possible. The barbarians of the avant-garde were already at the gate—they just needed a place of their own.

The locus of that change was Ferus, launched in 1957 by med-school dropout (and future museum curator) Walter Hopps and the assemblage artist Ed Kienholz. Although Ferus held exhibitions, the gallery initially served as more of an ad-hoc artists’ hangout than a commercial venture. But recently transplanted from New York and itching to get into the art business, Irving Blum soon entered the Ferus orbit—and, as it turned out, fortuitously, since Kienholz had recently decided that the gallery was occupying too much of his time and wanted to refocus his energies on his art. In 1958, Kienholz sold his share of Ferus to Blum, who promptly went about remaking the gallery, seeking out a more visible space, attempting to build a healthy client list, and soliciting further financial support to help the budding enterprise sustain itself—and, with any luck, grow.

With his elegant manner and flair for promotion, Blum proved the perfect foil for the bohemian intellectual Hopps, and between them they attracted a wide cross-section of L.A. characters: patrons of the arts; students; scions; and actors like Dennis Hopper and Vincent Price. Then there were the Ferus artists, a group that would eventually include John Altoon, Larry Bell, Billy Al Bengston, Robert Irwin, Craig Kauffman, Ken Price, and Ed Ruscha, many of whom took inspiration from California car-and-surf culture. Blum honed the roster and ventured to show more East Coast artists, including Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Frank Stella, and Andy Warhol, who Blum had first met in New York in 1961. At the time, Warhol was working on cartoon paintings that Blum struggled to make sense of. But during a visit to Warhol’s studio the following year, Blum noticed his newest works, the soup-can paintings, and decided he that wanted to show them at Ferus—a remarkable coup only in hindsight, as Pop was not yet the cultural and market phenomena it would become. Initially dismissed by many—an art dealer down the street offered actual cans for sale at 29 cents each—the soup-can paintings are now among the most iconic works of Pop art and reside in the permanent collection at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

This summer marks the 50th anniversary of the soup-can exhibition at Ferus. In honor of the occasion, Interview’s chairman, Peter M. Brant, recently spoke with Blum, 81, in Los Angeles to discuss what led the young art dealer to Warhol, the advent of Pop, and the conspiring forces that helped create the landmark exhibition that ushered in a new era in American art.

PETER BRANT: I know that you’re originally from Brooklyn, but you moved out West with your family when you were young.

IRVING BLUM: I was about 11 or 12 years old when we left Brooklyn. My father had arthritis, so we moved to Phoenix for the weather. I went to high school there, then to college at the University of Arizona, and then I was in the Air Force for about three and a half years. But when I got out in 1955, I went back to New York and, soon after arriving, I went to lunch with a friend who happened to bring along Hans Knoll.

BRANT: Knoll was really major in terms of design and modernism at that time. Florence Knoll, who, as you know, was an architect, developed furniture designs by some very important architects.

BLUM: Yes, Knoll was absolutely central. So Hans and I met and had a wonderful afternoon, and he said, “Why don’t you come up to the showroom and take a look around?” So I went up to their showroom and liked very much what I saw—I knew nothing about contemporary furniture at the time, but it seemed really interesting to me. So Hans asked, “What are you doing in New York?” And I said, “Well, I don’t know. I’m thinking about maybe doing something with theater.” I had worked for the Armed Forces Radio Service when I was in the Air Force and studied theater a little bit. So he said, “I’ll tell you what. Why don’t you come here and work for me, and if you stay for a year then I’ll give you a bonus, and then you’re free to do whatever you like after that. But it’s a way to ground yourself.” And I thought, “Perfect. Why not?” I really had nothing going on at the time. Knoll back then was on 57th and Madison, and most of the galleries in New York at that time were on 57th Street—Sidney Janis, Betty Parsons, they were all just around the corner. Leo [Castelli] hadn’t begun yet.

BRANT: Had the Seagrams commission started yet?

BLUM: Yes, it had started, and Mrs. Knoll was very involved in doing the corporate offices, so I had a bit of a hand in that. But I would visit the galleries—Janis and Parsons in particular—and I started to have the sense that there was something enormously important going on in the New York art world at the time. Then I met David Herbert, who worked for Parsons, and he took me around to some studios—including, most importantly, Ellsworth Kelly’s—and I ultimately had the feeling that I might want to have a gallery of my own.

BRANT: But up to that point, you had no idea that you were going to be involved in the art world.

BLUM: No, no idea. It just happened . . . Well, what happened really was that Hans Knoll died—he was killed in an automobile crash. He went down to pre-Castro Cuba and was run off the road and died. But Hans was largely responsible for a great deal of the energy in the company, and without him, the company changed. The romance was gone. I decided then that I might want to have a gallery. I also missed the West Coast. So I thought L.A. might be the place to try. This was 1957. I had very little money; I knew I couldn’t do anything in New York. So I came to L.A. and wandered around. There were several galleries here at the time—Frank Perls, Paul Kantor, Felix Landau, Esther Robles. But the most interesting gallery to me was the one that was started by Walter Hopps and Ed Kienholz a few months before I got there: the Ferus Gallery. So I met Walter and said, “You know, I’d like to participate in some way in this gallery that you’ve started.” He said, “Well, Kienholz has been complaining that he wants to go back to his studio to make work. You might have a conversation with him.” So I reached out to Ed and said, “I’m very interested in buying your share of the gallery.” And Ed said, “Great! I’m tired of sitting there.”

BRANT: “I want to go back to work!”

BLUM: Exactly. So I said, “Well, what sort of money are we talking about here?” He said, “$500.” And I said, “I can do that.” So I gave him $500 and Walter and I became partners.

BRANT: What was the gallery like at that point?

BLUM: It was completely chaotic. Number one, they represented around 60 people; and number two, the space was really uninteresting. It was behind a little antique store on La Cienega Boulevard. So I told Walter, “We need a more attractive space.” And he said, “How are we gonna do that?” And I said, “Well, maybe I can go to a few people and see if I can put a little money together. Who comes by in a regular way?” Not very many people came in . . . Vincent Price came in. Gifford Phillips came in. An astonishing lady by the name of Sayde Moss came in.

BRANT: Dennis Hopper would always tell me that when he was first starting out, Vincent Price was a big influence. Both Dennis and James Dean spoke regularly with Vincent, who was really encouraging of their interest in art.

BLUM: Well, there weren’t a lot of people involved in the gallery at the time. Vincent wouldn’t do anything, but the mere fact that he was interested in art was kind of radical and important, you know? Gifford wouldn’t do anything either, but he said that he would come to the gallery and buy things and support us in that way.

BRANT: But Sayde Moss became the backer of the gallery, right?

BLUM: Yes, she was the backer. Sayde’s husband had recently passed away, and she was looking for something to do, so I was able to persuade her that if she advanced us small sums of money, then we could do something that I thought might be important. When I say small sums, she gave us, at the end of a year’s time, say, for example, $5,000. The second year, she gave us $6,000. In any case, I found a space across the street from where Walter and Ed were located, and we were off and running. Then the next thing I did was reduce the number of artists that the gallery showed. I also wanted to include artists who didn’t live in California—particularly people from New York whom I’d met, like Ellsworth, or whom I’d known about early on, like Frank Stella.

BRANT: Stella was represented in New York by Leo Castelli at that time.

BLUM: Yes, by then Leo was in business. I took a lot of my cues from Leo, and he was just incredibly generous. Just to tell you one story: I came to New York around 1960 and went to see him. He had just begun in the same way that I had just begun. So I said, “Leo, the artists in California are intrigued by Jasper Johns, but they’ve never seen an actual painting—they’ve only seen reproductions. Can we do something?” He said, “Oh, dear. Jasper supports my entire gallery. I have a waiting list for the work of three or four people.” Then Leo thought for a minute, and he kind of drummed on his desk and said, “I’ll tell you what. Here is his phone number. Call him and maybe something will happen.” Can you imagine one dealer doing that for another?

BRANT: Well, Leo’s idea of the art world was much more inclusive. He liked to develop relationships with other dealers who he knew really understood what he was doing.

BLUM: Yeah, Leo was really incredible—just extremely fair and generous. He had this group of “lieutenants” that he did a lot of business with: Joe Helman in St. Louis, Bruno [Bischofberger] in Switzerland, Ileana [Sonnabend] in Paris, Robert Fraser in England, Gian Enzo Sperone in Italy.

BRANT: Akira Ikeda in Japan.

BLUM: Exactly. I became Leo’s guy on the West Coast. So Leo gave me Jasper’s number and I called Jasper right there on the spot and he invited me to his studio. As I walked into his place, I saw a [Kurt] Schwitters collage in the entryway that he had traded a dealer for, and then a long table with his sculptures—the light bulb, the flashlight, the ale cans. Nothing in my career up to that point had prepared me for what I was looking at. I said, “What are those?” Jasper said, “Sculptures that I’ve been thinking about.” I looked at them and thought, Go for it. So I said, “I’ve got an idea, Jasper. The Schwitters collage and your sculpture—we could do a show in my gallery in California.” He said, “Well, where are you gonna get the Schwitters?” I said, “A German expatriate lady who lives in L.A. by the name of Galka Scheyer has a group of them.” And he said, “Well, if you get the Schwitters, then call me and I’ll send you my sculptures.” And I got them. So I had that show with Schwitters and Jasper . . . I kept two sculptures and sent the rest back. [laughs]

BRANT: At least you kept two of them.

BLUM: They were roughly $500 a piece. Unbelievable.

BRANT: And the Flag paintings were only $1,000 back then. But making an actual sale at that time was a rare occasion.

BLUM: A rare occasion. I mean, you could hardly do it. Thank heaven Gifford Phillips supported an artist we showed called Hassel Smith, who lived north of San Francisco. That helped a lot.

BRANT: I know that you raised a bit of extra money back then by doing some script work on the side.

BLUM: Yeah, for Russ Meyer. [laughs]

BRANT: But he wasn’t Russ Meyer yet when you met him.

BLUM: No, when I met him, he was a still photographer. He’d never directed a movie. He had no reputation yet. He was merely a friend. We used to play poker up at his house. I liked him—he was crusty and very entertaining. His ambition, though, really was to make a movie, and I helped him to achieve that ambition with The Immoral Mr. Teas [1959], which I wrote and presented to him, having taken virtually all of it from The Secret Life of Walter Mitty by James Thurber. [both laugh] But Russ thought it was great.

BRANT: You were the narrator of that film as well.

BLUM: I was the narrator as well. But in any case, I separated from Russ after that one attempt because the gallery started to occupy more and more of my time.

BRANT: How did you come to meet Andy? What were the circumstances?

BLUM: Well, my idea was to put artists from the East Coast together with people I represented on the West Coast, and in order to do that I had to go to New York. I never had a lot of money, so I could only go maybe once a year. So I was pressed for time while I was in town. In order to see as much as possible, I nominated three or four of my own lieutenants who I would correspond with before I arrived to ask if they had any studios that they could recommend that I visit. Dick

Bellamy of the Green Gallery was one of them—he was a great friend. Henry Geldzahler—before he became Henry Geldzahler—was another one. And then there was David Herbert, of course, and Bill Seitz, who was then a curator at the Museum of Modern Art. They essentially did the editing for my visits.

BRANT: You had great people advising you—and they were obviously sending you to the right studios.

BLUM: I was very lucky. Bellamy was enormously astute—as was Henry.

BRANT: When did Andy start showing up on their lists?

BLUM: I was about to go to New York in 1961 and I got lists from Geldzahler, Bellamy, Seitz and Herbert. There were a half dozen artists on each list, and Andy’s name appeared on Geldzahler’s and Bellamy’s. So I called Andy when I got to New York and explained what I was doing and where I was from. He said, “Come on over.” So I went to his studio, and there, leaning up against the wall, were three or four cartoon paintings, which he proudly showed me. But I couldn’t make heads or tails of them.

BRANT: They were totally out there, those early works.

BLUM: Yeah, the paintings seemed not radical to me, but rather strange. I didn’t understand them. But I had a wonderful conversation with Andy. He kept asking me about movie stars and studios that I’d visited. He wanted to know everything. Andy was incredibly curious—I liked that about him. I must have stayed for an hour or two. Finally I thanked him for letting me visit and said he would hear from me again, but in truth I put the experience out of my mind. Then about six months later I got a call from a collector in L.A. named Edwin Janss.

BRANT: A great California collector.

BLUM: Great California collector. He put together amazing material. But he was just beginning to get involved back then. He said, “You know, I’ve been looking through some art books and I’ve gotten interested in Giacometti. Do you know anything about Giacometti?” I said, “Oh, yes,” which wasn’t true. But he said he was going to New York to see a painting at the Perls Galleries and asked me to come along, which I agreed to do. So we flew to New York and he bought the Giacometti painting and then he said to me, “I’m going on to Europe from here. I’ve paid your way back, but now you’re on your own.” So the following day I went to see Leo, and as I walked in, [Castelli director] Ivan Karp said, “Look at these.” He held up a little transparency viewer. I took it and I was looking at cartoons. I said, “Andy Warhol!” And Ivan said, “No, these are by a guy who lives in New Jersey. His name is Lichtenstein. We’re thinking about showing him.” I looked hard at those cartoons. They somehow seemed more finished than Andy’s paintings. But I remember distinctly making a connection, with the heavy black outline . . . I thought that there was something going on that I could either participate in—or not. So I said to Ivan, “Look, I want to show this guy in California.” And Ivan said, “We’re showing him here. I’ll organize it.” It was something Roy Lichtenstein never forgot, that early support. He was very appreciative.

BRANT: He was a wonderful guy.

BLUM: I really adored him. Among the artists, I was probably closer to Roy than anyone else. But in any case, I left the gallery and called Andy immediately. I wanted to compare his paintings to what I now had in my head. Andy said, “Come on over.”

BRANT: This was when he was in the firehouse, right?

BLUM: It was a little townhouse on Lexington Avenue, as I recall. In any case, I walked down a corridor, and there were paintings of soup cans on the floor, leaning against the wall. I said, “Andy, what are those?” He said, “Oh, I’m doing these now.” And I said, “Why more than one?” One seemed to be a replica of the others. He said, “I’m going to do 32.” I simply couldn’t believe it. I said, “Why 32?” He said, “There are 32 varieties.”

BRANT: Obviously those were not the works you were expecting to see. What about the cartoon paintings?

BLUM: The cartoons were nowhere in view. I didn’t even bring them up. I kept thinking about the soup cans. I asked him, “Andy, do you have a gallery?” He said, “No, I don’t.” So I said, “Um . . . What about showing these in California?” And then he stopped. I could sense that he was thinking that he did these pieces in New York, his friends were in New York, his audience was in New York . . . California? It was slightly foreign. But I remembered the previous conversation I’d had with him, so I took his arm and said, “Andy, movie stars come into the gallery.” And he said, “Let’s do it.” That was it. He finished the 32 soup cans in 1962 and sent them to me.

BRANT: So you both committed to a show of all of those soup cans. Then Andy drove out to L.A. with some friends, right?

BLUM: Yeah, he drove out here. He came out a couple of times. Later, he came with Nico.

BRANT: Tell me about how you hung the pictures in the gallery. It was not a conventional installation.

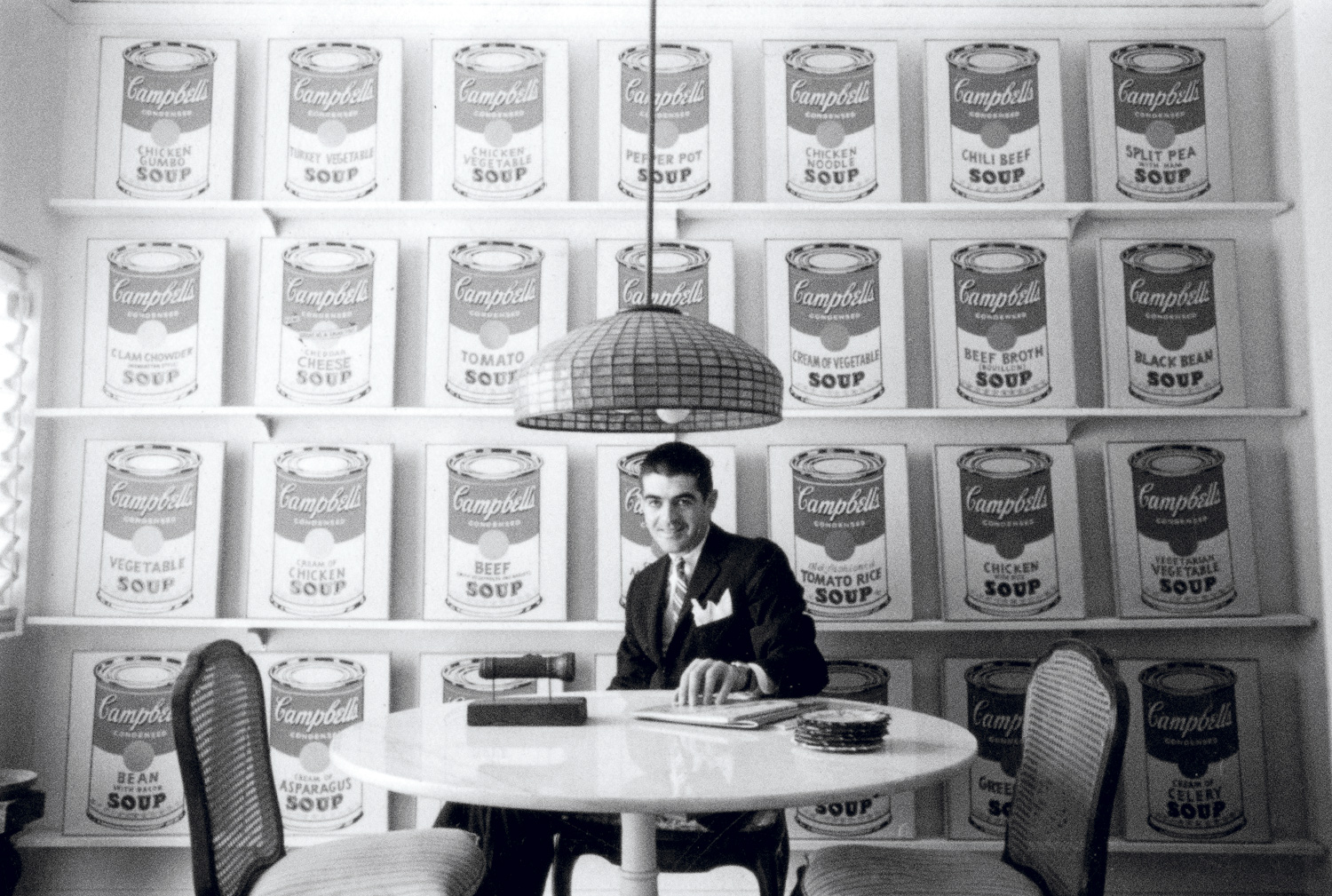

BLUM: What happened was, the paintings arrived, and I began to hang them in the gallery in June of 1962—the exhibition opened in July. But I remember that they didn’t look straight on the wall. I measured it out, but somehow I couldn’t get them to look straight. So I hit on the idea of putting them on a little shelf, which gave me exactly the effect that I wanted.

BRANT: You were playing on the idea of the soup cans as commodities.

BLUM: Cans sit on shelves. Why not? So we showed the paintings that way and had our opening. We sold four or five paintings for $100 apiece. And then halfway through the exhibition I had the idea of keeping the group of them intact. So I called up Andy and said, “I’m going to call these people and see if I can’t retract their purchases.” He said, “Great.” He liked the idea of keeping them together.

BRANT: How did you get back the five soup cans that sold?

BLUM: Well, I called the people who bought them, including Dennis, Betty Asher, Don Factor, Bob Rowan, and Edwin Janss, and I said “Big favor . . . This is important to me.” And they were agreeable. They had never received their paintings; the works were still in the gallery. So when I knew I had them back, I called Andy and said, “What do you want for them?” He said, “$1,000.” To me $1,000 was quite a bit of money then, so I said, “How long would you give me to pay you?” He said, “How long do you want?” I said, “I want a year.” He agreed, so I sent him $100 a month for 10 months. I had a little apartment and I remember taking the soup cans out of the gallery and hanging them in my dining room, four rows of eight, so that all 32 were on one wall. I thought that they were absolutely extraordinary and strange—and important, although I didn’t have confirmation of that from anyone else. [laughs] But I explained to each of the people who originally bought them what I was doing, so there was no problem.

BRANT: Well, I know you were friends with most of your clients anyhow.

BLUM: Peter, I wasn’t selling to anybody else at the time. [laughs] I had five clients—and it was that way for five years. But I was very friendly with all of them.

BRANT: I know that you had a very good relationship with Dennis.

BLUM: Dennis was incredible. He was taking pictures all the time, and I used a lot of his photographs as announcements for various shows that I had at the gallery. The guy absolutely in one glance got the Pop spirit. He got it in a way that nobody got it at that time.

BRANT: What about the critical reception to the show. Do you remember the response at the time? What were the reviews like?

BLUM: They were dreadful.

BRANT: I’m sure. Andy didn’t get very many good reviews—ever. There were always variations on the same questions and criticisms. Was he a commercial artist? Was he a sellout? Was he a promoter?

BLUM: It took forever for people to come around to what he was doing. Now it’s easy to see his importance and his influence, but at the time it was veiled.

BRANT: The Abstract Expressionist artists didn’t really care for him.

BLUM: No, not at all . . . Well, he helped do them in. But then, in 1962, as soon as the Pop style hit, there were suddenly 300 Pop artists. Everybody was working in that style.

BRANT: And now Pop is so much a part of the cultural history of the United States. That show is a kind of quintessential moment, an adventure of going West, which was a big adventure for somebody like Andy. And then you there, this good-looking Cary Grant figure . . .

BLUM: [laughs] Well, I was excited by those soup cans. I kept them for more than 20 years.

BRANT: You gave them to MoMA in 1996 as a partial gift.

BLUM: Plus $15 million.

BRANT: During the period that you had the soup cans, did people approach you with any offers to buy them?

BLUM: Yeah, people did try to buy them, but I wasn’t really interested in selling. My idea was that they would ultimately go to a great museum. I thought they had that kind of resonance.

BRANT: It also spurred MoMA on to acquire more of Andy’s work. Now that they’re 50 years old, it’s hard to even put a value on those 32 soup cans.

BLUM: If I was forced to, I would probably say they’re worth around $200 million. I think that sum could probably be achieved. In any case, if I owned them today, that’s certainly what I would ask for them.