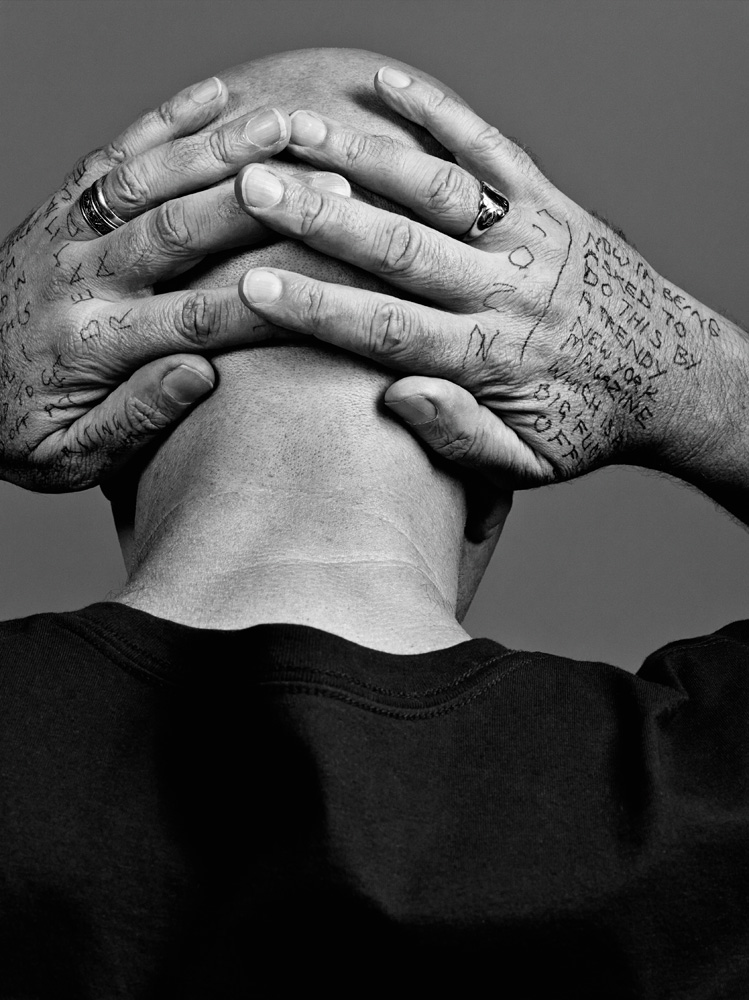

Irvine Welsh

I WAS JUST GOING THROUGH THIS NEW BOOK I’VE FINISHED AND I THOUGHT, ‘THIS GUY WHO WROTE THIS THING IS A FUCKING SICK BASTARD.’ Irvine Welsh

“I just move on,” says Carl, one of the characteristically Welshian narrators of Irvine Welsh’s 2001 novel Glue. Carl is a man on the move, escaping himself, eluding his demons, moving from country to country, never stopping, never waiting for the boredom or banality to catch up with him. “The conventional wisdom is that you’re running away, you should learn to cope with being fucked-up,” he says. “I don’t hold with that. Life is a dynamic rather than a static process, and when we don’t change, it kills us. It’s not running away, it’s moving on.”

Welsh, too, has moved on—with the same unabashed propulsiveness of his prose—from one celebrated novel to another, from one medium to another (from the rabid success of his debut novel, Trainspotting, in 1993, to his work as a screenwriter and then as a film director in the aughts, and now on to TV, where he is developing a pilot for HBO). He’s even moved on from his native Edinburgh, Scotland, to the balmy climes of Miami. So, could it be said of Welsh, who, at 55, will soon release his ninth novel, The Sex Lives of Siamese Twins (Doubleday, spring 2015), that the ultimate hardcore stylist has gone soft? Or at least tan? Can it be said that he followed the dictum laid down in dripping irony by the narrator of Trainspotting to “Choose Life. Choose a job. Choose a career. Choose a family. Choose a fucking big television”? Well, you could say that, but we wouldn’t want to be around for the ensuing dustup.

If by some horrific happenstance, you are not well acquainted with Welsh’s prose (including the novels Filth, 1998, and Porno, 2002, as well as the story collections The Acid House, 1994, and Ecstasy, 1996), but are familiar with him only by way of the film adaptations such as Trainspotting (1996), we have good news for you: This month James McAvoy stars as the jigsaw-crooked Edinburgh Detective Sergeant Bruce Robertson, spiraling toward a rock-bottom of drink, drugs, and depravity in a colorful adaptation of Filth, alongside Jamie Bell and Imogen Poots. And then there are those rumors that Welsh is getting the gang back together for a sequel to the landmark Trainspotting, which, among other things, announced to the world the star power of Ewan McGregor and the talents of director Danny Boyle.

Welsh, who has always been a great fan and a sometime player of music, definitely does choose friends. He met and befriended Peter Hook, co-founder of Joy Division and New Order, through a group of mutual friends that included the late Factory Records impresario Tony Wilson, and the two have been pals through many years of both habits and health. In February, Hook called up his mate from Cheshire, England, to find him driving …somewhere in Florida. -Christopher Wallace

PETER HOOK: Hi, mate. Whereabouts are you?

IRVINE WELSH: I’m in Miami. Well, I’m actually on the 95 heading up to Wellington.

HOOK: You’re on a car phone?

WELSH: I’m in a car. But I’m not driving it, so don’t worry. [laughs]

HOOK: I was hoping you would be driving. I’m juggling and talking to you at the same time. What kind of car is it?

WELSH: It’s a hybrid Fusion.

HOOK: Bloody hell. I’d thought you’d be in a Mustang, mate.

WELSH: Well, I only learned to drive this summer.

HOOK: Did it give you a warm glow?

WELSH: I just about shat myself. [Hook laughs] But the guy passed me. He says, “You’re too cavalier on the corners. You have to slow down a bit taking the corners. But, otherwise, I’m going to pass you.” Fucking hell.

HOOK: I’m still driving a 6.3 liter V8 Mercedes twin-turbo, mate. I haven’t got to that bit of saving the planet yet. So how are you enjoying Miami?

WELSH: I’m enjoying it. I just missed all the worst weather. I’ve been completely spoiled down here. I came down just after Christmas and I went to Colombia for a few days.

HOOK: Were you doing research?

WELSH: Not any active research. [both laugh] I didn’t get any work done …

HOOK: Your car phone’s gone really bad there. It’s going distorted. As a punk, I like that, but I can’t hear a bloody word you’re saying.

WELSH: Over and above me being Scottish?

HOOK: [laughs] Much over and above that. I loved that when you said you’d missed all the bad weather this year and I’m thinking, “Hang on, didn’t you grow up in Edinburgh?” You’ve had enough bad weather to last you a lifetime, haven’t you? Not much better than me in Manchester.

WELSH: I’ve done my time.

HOOK: We’re both from a working-class background, and we’ve both had a modicum of success that has taken us to a more affluent place. I bet you didn’t think for one minute you’d end up living in Miami, did you?

WELSH: I didn’t. I didn’t think I was even going to end up living. [laughs]

HOOK: It’s quite interesting that you’ve kept your working-class, shall we say, demeanor, even though you are living in a middle-class environment.

WELSH: I would say more upper class, because most middle-class people I know don’t really live like me. [Hook laughs] No, seriously. Middle-class people worry a lot about money. They worry a lot about job security, and they do a lot of nine-to-five stuff.

HOOK: You’re like me—we had no money for a long time. I remember when we had all our problems with the Haçienda [a legendary, and legendarily ill-fated Manchester nightclub, backed by members of New Order from 1982 to ’97], and we were all at each other’s throats. [Haçienda partner] Tony Wilson always said, “You’ve got a lot to thank the taxman for.” And I said, “How do you work that out?” And he said, “He’s kept you so miserable, you still make great music.” [Welsh laughs] It has to be said that the worst thing about any art is that when you do get success, it does tend to water down the work, doesn’t it?

WELSH: It does. You get complacent. You get comfortable. And that’s the thing that you’re always trying to guard against.

I USED TO GO OUT AND TAKE A COUPLE OF PILLS AND GET FUCKED. AND ON THE COMEDOWN, I COULD JUST KEEP WRITING AND IT WAS FUN. BUT IF I DID ANYTHING LIKE THAT NOW, I’D JUST WANT TO LIE IN BED AND SWEAT AND FEEL SORRY FOR MYSELF. GETTING SOPPED UP IS A YOUNG GUY’S GAME. Irvine Welsh

HOOK: When your books are made into films, does the lack of control you have in their adaptations drive you mad?

WELSH: Filmmaking is a much more collaborative thing than literature, so you know you’re going to be working with a group of people at the start. You know it’s going to be a compromise.

HOOK: Oh, man. It’s always a bloody compromise—like when we did 24 Hour Party People [2002]. It’s all to do with the backers, isn’t it? I’m glad we found Anton Corbijn with Control [2007]. Anton financed the film himself.

WELSH: For Filth, we had about 12 producers on the thing. The opening credits go on for months. Most of them are actually financers rather than producers. And the only way that we could raise the budget without interference from a studio was to have a lot of different financers on board.

HOOK: Is that bribery and corruption, then?

WELSH: You kind of buy a producer’s credit, yeah. [Hook laughs]

HOOK: So how much have you done on Trainspotting 2?

WELSH: We’re just talking about it now. I’m hoping that John [Hodge] writes it, because I don’t want to touch it. [Hook laughs]

HOOK: When I first saw Trainspotting—and don’t forget, I’ve toured with the Happy Mondays—Trainspotting was quite a shocking film.

WELSH: It still kind of holds up. It still has that visceral feel.

HOOK: A lot of that has to do with the shooting, right? It’s shot so well.

WELSH: Brian Tufano, the guy who shot it, did Quadrophenia [1979] as well. And Danny’s an incredibly special director. Some of them are more interested in working with the actors, but Danny’s such a good stylist.

HOOK: What are you going to do in Trainspotting 2, make them all respectable? [laughs]

WELSH: I mean, Trainspotting is a rite-of-passage movie about a group of young guys growing up and getting involved. But these guys wouldn’t really be together in middle age.

HOOK: We know from experience that everyone gets scattered to the four winds.

WELSH: That’s the thing. And given the different personalities, how do you actually make a reunion seem plausible? What do you actually get them to do together? If we can resolve that question, I think the film will go on.

HOOK: Were you happy working on the film after doing the book? I mean, I know a little bit about how engrossed you get in the world you are writing.

WELSH: You’re on your own with the book. And while you are writing fiction, you’re spending all this time with people who don’t actually exist, which is just madness.

HOOK: That is what madness is, actually.

WELSH: And then you finally stop to talk to real people on the movie, which is great, because it’s much healthier. But then again, you’re not playing God anymore. You’re just one of the team.

HOOK: Does your imagination shock you sometimes?

WELSH: Yes. But not at the time, not when you’re actually writing. I was just going through this new book I’ve finished and I read some of the things back and thought, “This guy who wrote this thing is a fucking sick bastard.” [Hook laughs]

HOOK: When you’re working, you’re lost in it, aren’t you? That’s such an achievement. And one of the things about going from music, which is very collaborative, to doing the book, is it’s only your point of view. Even if the book is the story of many people’s lives.

WELSH: Did you enjoy doing the writing on your book about the club [The Haçienda: How Not to Run a Club, 2009] and on your Joy Division book [Unknown Pleasures: Inside Joy Division, 2012]? Did you enjoy just sitting down and writing?

HOOK: I did. I mean, I was always the loudest storyteller. I used to tell these stories whenever I was drunk. They become part of your act, you know, whenever you’re pissed off your head. In anything that you do as a musician, whether you admit it or not, you’re always craving that audience—people listening to you, people watching you. And I suppose it’s the same thing with the book—you want to tell the story. I found the book quite easy to write. It was the bloody rewrites that kill you.

WELSH: That always got me. When you’re writing something fresh, it’s exciting. But when you’re rewriting it and rewriting it, it’s just a technical exercise to get it to sound and read good.

HOOK: And every time somebody asks me to read from it now, I think, “I could have written this miles better.” [laughs]

WELSH: Failure is kind of programmed into anything you do creatively. You can always see the faults and flaws in it. I’m the same when I do readings. I go out on the circuit and I just think, “God, that chapter was fucking shit. Why did I write it that way?”

HOOK: Your opinion and your aspirations change all the time. But are you clean now? Are you sober?

WELSH: No. I’ll still go and have a drink. Yesterday was the first day in a long time.

HOOK: I’ve found that you can make music when you’re out of it because you can drib and drab it. But you have to concentrate on writing. I don’t think I could’ve written those two books if I had still been drinking.

WELSH: I used to be able to do it. I used to go out and take a couple of pills and get fucked. And on the comedown, I could just keep writing and it was fun. But if I did anything like that now, I’d just want to lie in bed and sweat and feel sorry for myself. Getting sopped up in general is a young guy’s game.

HOOK: I was watching Filth and, like everything you write, it seems very British. Do Americans get it? I’m not being patronizing. When I did the Haçienda book, the American publishers, who were lovely, said, “Well, we’re going to have to translate it.” And I was going, “What?” And they said, “We’re going to have to translate it into American.” [laughs]

TRAINSPOTTING IS A RITE-OF-PASSAGE MOVIE ABOUT A GROUP OF YOUNG GUYS GROWING UP AND GETTING INVOLVED. BUT THESE GUYS WOULDN’T REALLY BE TOGETHER IN MIDDLE AGE . . . HOW DO YOU ACTUALLY MAKE A REUNION SEEM PLAUSIBLE? IF WE CAN RESOLVE THAT, I THINK THE FILM WILL GO ON. Irvine Welsh

WELSH: I think it probably does limit me. I mean, there are trendy kids who are going to get into Filth, but they’re all set on the East Coast and West Coast. There’s practically nothing in the middle of the country, apart from a few college towns.

HOOK: Well, thank god for subtitles then, mate.

WELSH: We actually did put subtitles in Trainspotting. A lot of the actors weren’t keen to do overdubs. Bobby Carlyle refused to overdub it because he felt that Americans just have to work a little bit harder to get it, and there’s nothing wrong with that. One of my books even has a glossary at the back.

HOOK: But you don’t find it hard to adjust to America?

WELSH: I think they probably find it harder adjusting to me.

HOOK: [laughs] And so they bloody should, mate.

WELSH: I have made more of an effort here. As soon as I get into a taxi back home, my voice is impenetrable again.

HOOK: Something I find that I do when we’re touring is, if I don’t want the locals to understand what we’re saying, I will lay it on a bit thick with the other lads. And it’s like a cloak. Now, is your new novel actually called The Sex Lives of Siamese Twins?

WELSH: It is.

HOOK: How did you research that? [laughs]

WELSH: Well, it’s about two women that become obsessed with each other—a personal trainer and a painter. The idea is that the personal trainer can’t get the artist to lose weight, so she kidnaps her and throws her in this penthouse building. She chains her to a bed and limits her diet. The idea for it came when I was in a fitness club one time and I heard this trainer shouting at this other woman who was in tears. I thought, “Why does this woman maintain this kind of relationship?” Maybe she’s just being sweet. Or they must get along.

HOOK: Masochistic. Is this your first novel set in America?

WELSH: I did one a couple of years back called Crime [2008], which was set in Florida as well. But this is the first one that’s all American characters, so in some ways it’s a bit of a departure.

HOOK: You’re also doing a television show for HBO called Higher with [Scottish DJ and producer] Calvin Harris. That’s wild, because a comedy set in the electronic dance music world is sort of like [This Is] Spinal Tap [1984].

WELSH: It doesn’t really need any parody; it’s already kind of ridiculous.

HOOK: Is it like It’s All Gone Pete Tong [2005]?

WELSH: Kind of. It’s got that kind of flavor to it. That’s what we’re trying to get to—the kind of Human Traffic [1999] feel to it, but with modern vigor, basically.

HOOK: And are drugs still big in dance music?

WELSH: The club that Calvin plays at in Vegas is very velvet rope and table service. It’s all about high rollers. These whales pick up young girls, and it’s all about alcohol and shots. But you’ve got the smaller clubs and the raves, and it’s much more about old-school raving. It’s much more about face painting.

HOOK: My mate lives in Vegas and he goes to a lot of small clubs, clubs that are off the strip, and he says that the way that you can buy coke over the bar is quite shocking. It’s like in London in the early ’80s, when you could get a round of drinks and buy a couple of grams over the counter. When I DJ’d in Vegas, I found that the locals weren’t into the music the way the kids were, because the kids were on alcohol and the locals were on coke. And coke is the worst thing for music in the bloody world.

WELSH: Andrew Innes of Primal Scream used to say you’re in E minor. [both laugh]

HOOK: So how far have you got with this show, Higher?

WELSH: It’s got that same problem—well, in some ways it’s good, but it’s got a lot of producers, so when you put something in to discuss, it goes around the house a bit.

HOOK: Are you used to that?

WELSH: I’ve gotten used to that now. Any collaboration you do, it’s all about the people you’re going to be doing it with. And the people that I’ve been working with over the last five years, in TV particularly, have just been really good people to work with, full of ideas and enthusiasm. But, I mean, when I first came out here, I was going around to all these different studios and they were all wanting to work with me after Trainspotting. And they’d say, “Well, who’s your agent? Who should we get in touch with?” And I never had an agent. I said, “Just get in touch with me.” And some of them looked at me like there’s a village missing an idiot back in Scotland. [Hook laughs] They just said, “Right. Okay, pal.” And I never heard from them again. I realized that you’ve got to do it all this way, so I got an agent and all that.

HOOK: They don’t mind talking to you about creativity, but they hate talking to you about money. You shouldn’t have that conversation with anybody, you know? Because it’s about the art. You have to pretend that you’re not interested in the money, and somebody else can do it for you. The first time we went to America, we went to a Warner Bros. party, and I was talking to the head of Warner, Mo Ostin, and he said to me, “Where’s your manager, Peter?” And I said, “My manager? He’s over there.” And Rob was lying on the floor with his head on the cushion, smoking a big, fat joint, doing no networking, fuck all. [Welsh laughs] I was so proud of him at that moment with that punk attitude. It sounds like you’ve certainly fallen on your feet, we could say. Doesn’t sound like you’re coming back, mate.

WELSH: I feel like the guy who’s been sent out to get milk and disappeared for years. I do think about going back, but it makes sense for me, being out here. You know, I’ve kind of got my feet under the table a bit now.

HOOK: Well, you take care of yourself.

WELSH: I will do, mate.

PETER HOOK IS THE LEAD VOCALIST AND BASSIST FOR PETER HOOK & THE LIGHT, WHO ARE SET TO TOUR NORTH AMERICA IN NOVEMBER.