In Conversation

Avram Finkelstein and Qween Jean Look Back on a Lifetime of Organizing

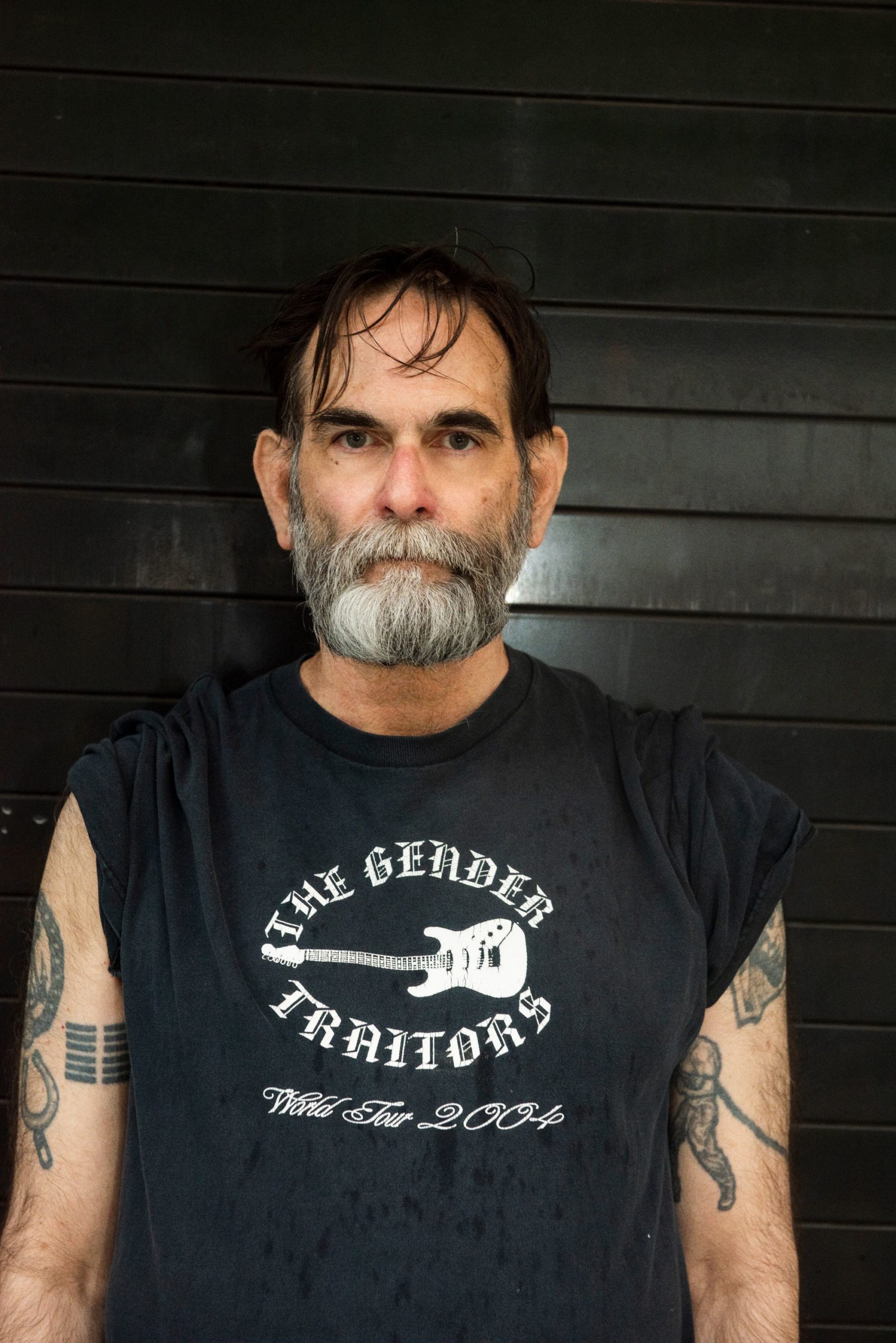

Photo by Ryan McGinley.

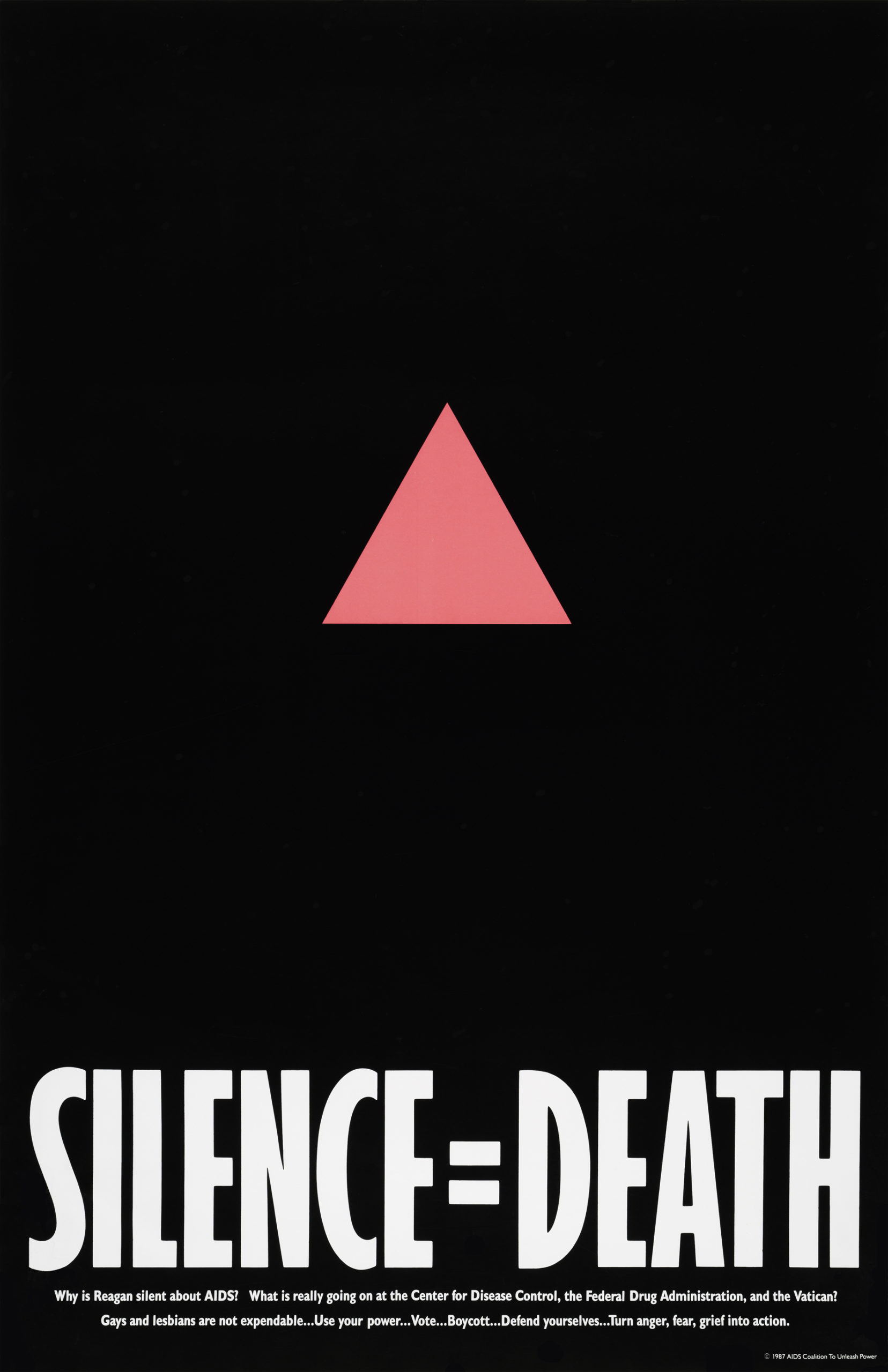

A pink triangle floating in black space. At the bottom, in white capital letters, SILENCE=DEATH. Rarely has a single graphic captured the spirit and urgency of a political movement as this 1986 poster by the Silence=Death Project, which became a flag, a warning call, and a badge of courage for the HIV/AIDS activist movement throughout the ’80s, and ’90s and deep into the 21st Century. Artist and activist Avram Finkelstein was a founding member of that six-person collective (and he later went on to form the in-your-face art-manifesto collective Gran Fury). His political and artistic stances—often wheat-pasted around the city and emblazoned on the front of t-shirts—not only saved lives and changed the language of protest, his vital work has gone on to inspire generations of activists, including those who have taken to the streets in the past year (continuing to fight for much of the same visibility and rights that brought Finkelstein and his peers to action during the darkest days of the AIDS crisis). This month, New York’s David Zwirner Gallery is celebrating the watershed work of the Silence=Death Project with a show that traces its social, political and artistic impact, much of the material coming from Finkelstein’s own archive. Not only that, but a limited-edition Silence=Death print will be available for purchase on here, with proceeds benefiting Visual AIDS. It’s all part of a multi-site series of exhibitions that David Zwirner Gallery is hosting that honors the fortieth anniversary of the CDC report, acknowledging the existence of HIV. The series, entitled, “More Life,” includes shows on directors Derek Jarman and Marlon Riggs, and the photographer Mark Morrisroe specifically curated by Ryan McGinley. While McGinley shot Finkelstein’s portrait for Interview, we asked artist and activist Qween Jean to talk to their queer brother-in-arms about keeping the fight going and how a poster that changed the world started with a simple dinner among friends.—CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

———

ACT UP Demo Federal Plaza NYC June 30, 1987. From left: Steve Gendon, Mark Aurigemma, Douglas Montgomery, Charles Stinson, Frank O’Dowd, Avram Finkelstein. Photo: Donna Binder ©DonnaBinder

QWEEN JEAN: I think a lot of folks make assumptions about people based on what they see. So I want to start by asking you, how do you show up in the world?

AVRAM FINKELSTEIN: That is a loaded question and a really good one. I think that each of us has a responsibility to everyone around us and to the entire world. History is shared. I have complex feelings about the idea of storytelling. One set of ideas surrounding storytelling has to do with representation and historiography and all of the things that we need as activists in marginalized communities to know our own history. But I do think that stories are all we have. In fact, rights can be given and rights can be taken away, but stories cannot be.

QWEEN JEAN: That resonates with me a lot. What would you say has been the arc of your story?

FINKELSTEIN: Both of my parents were in the American Communist Party and I was raised on the left. In the same way that if your parents were stockbrokers you want to go into a financial trade. I was born with a political poster in my hand. So I think I see the world distinctly from that perspective. But I also feel like the ways in which histories are written, and we’re seeing it with COVID-19 and in so many other ways that define the current moment, that we’re actually watching history be constructed as it unfurls. I think that the story of HIV/AIDS and my work with the Silence=Death Collective and with Gran Fury is a part of a dominant narrative that doesn’t really represent all the counter narratives that existed before, during, and after. So I’m really obsessed with teasing out the counter narratives.

QWEEN JEAN: But what really drew you into community work and activism? Was there a particular event or series of events that really affirmed your purpose?

FINKELSTEIN: As I said, I was raised on the left. I stuffed envelopes for the poor people’s campaign and I worked for the student mobilization to end the war in Vietnam. So I was always politically active. But it wasn’t until the man I had decided to build my life around started showing signs of immunosuppression in 1979 and 1980, that I really connected my idea of political agency to my queerness, to my identity. I’m very loath to say good things came about as a result of the early days of the AIDS crisis in America, but in terms of my personal story it connected me to my community. It connected the two halves of myself—the political self and the queer self. And it connected me to a community of people which helped me grow to the next step. I think that politicization is a process of constantly taking the next step for yourself. People would describe me as having a very political life, but the queer community helped me to understand how that related to the needs of queer activism.

QWEEN JEAN: A lot of us grew up seeing Silence=Death and recognize the pink triangle. I’d love to hear about the origins of those symbols and their true intentionality.

FINKELSTEIN: After my boyfriend died in 1984, I reconnected with an old friend, Jorge [Soccarás] who had also lost someone, although I didn’t realize it was to AIDS. Jorge had brought another friend to this dinner, and the three of us started talking and realized we needed a space to explore the question of AIDS from a political perspective. We formed a small consciousness-raising collective based on feminist organizing principles. And I suggested we each invite one person who the other two didn’t know so there would be political tension and we would be able to grow. We met every week, and it started out being about our fears and anxieties and trying to figure out what life was going to be like in this new world. But every week we would end up talking about politics. I remembered that in the ’60s, when people needed to communicate, they used the streets. New York was a very activated space in that way. So I suggested that we make a poster to the collective. We spent almost nine months working on it and it went up literally two weeks before the formation of ACT UP. When you think of it historically you think it came out of ACT UP, but it didn’t. It came out of a group of six people who met every week a full year before ACT UP formed. The reason I think that’s significant is that while there’s power in collective action and in large movement organizing, there’s also power in the individual voice. I think we tend to forget that.

QWEEN JEAN: I’m literally writing notes on the power of the individual voice! I’ll be honest, I really feel like I’m living that a little bit right now.

FINKELSTEIN: You are.

QWEEN JEAN: What do you think has been left out of that history that was so important to that organizing?

FINKELSTEIN: I think that all of the counter narratives fell by the wayside, because in the storytelling of late capitalism, the stories that are easiest to tell are the ones that are privileged. So, the whole idea that an embattled community fought for access to drug therapies and changed the way research and drug development worked, and lives were saved, that’s a really great story. That’s not the entire story. It leaves out the people doing work around IV drug use in ACT UP. We had a four-year campaign to get the Centers for Disease Control to change the definition of AIDS to include the manifestations of immunosuppression in women and IV drug users. There was a Latino caucus, there was a majority action caucus. There was so much work that doesn’t tuck underneath that more convenient narrative, which supports the idea that, look, dissent works and capitalism can change and now we’re all happy. It totally ignores the fact that Reagan was president, Washington DC was deregulation mad, and we were asking for something that pharmaceutical companies were really happy to give, which is more drugs more quickly. We were also implying that there would be a marketplace. So the story of HIV/AIDS doesn’t even scratch the surface of the realities of it.

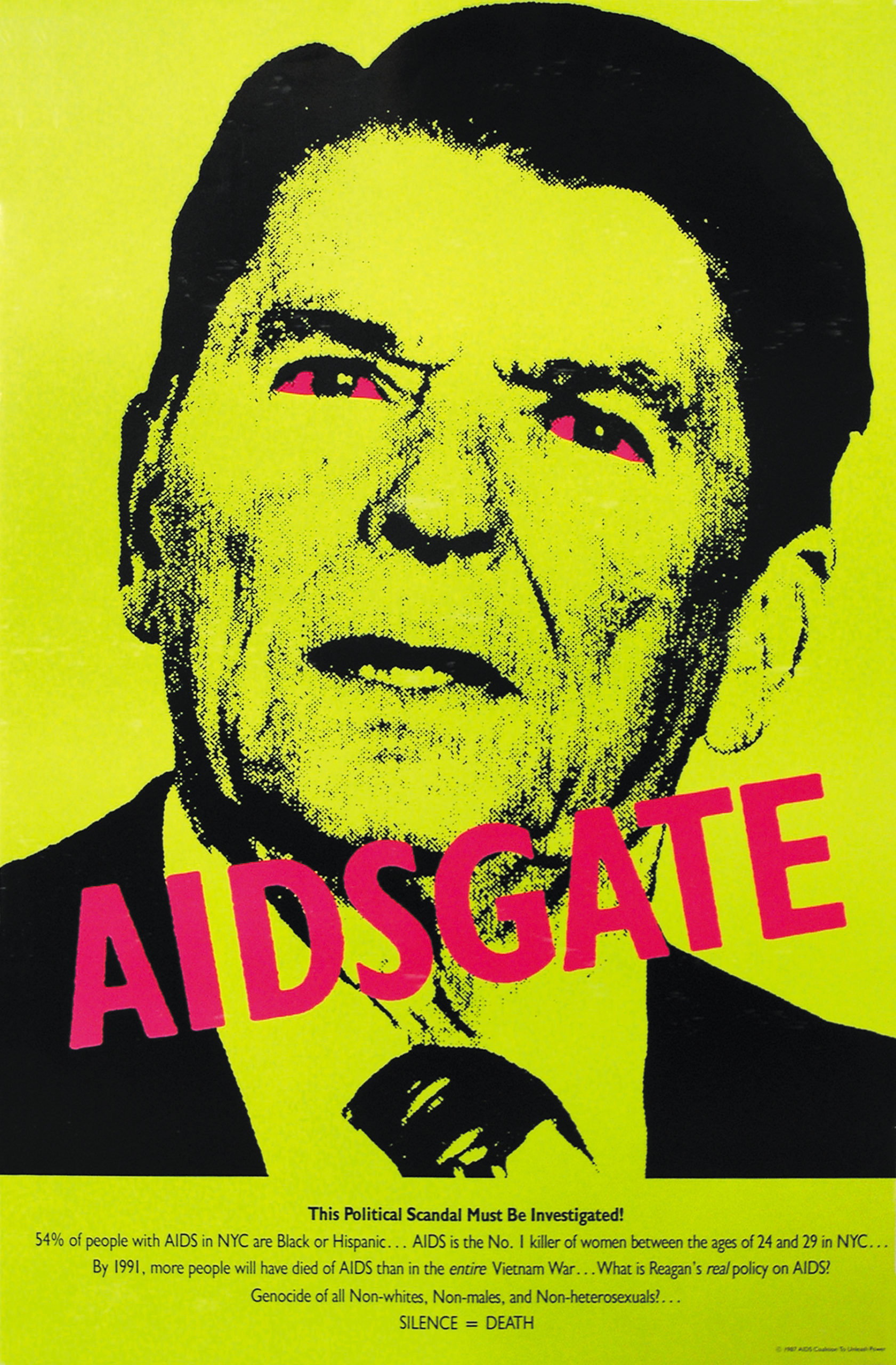

You asked earlier about the pink triangle. When we were deciding on the poster, the first idea was to make a poster in response to William F. Buckley’s editorial calling for the tattooing of HIV positive people—on the butt for if you were queer and on the arm if you were an IV drug user. And as we began to think about it, we thought okay, well that involves a photograph of a tattoo. So what gender is that arm? What color is that butt? We realized we couldn’t include what was obviously going to impact all communities. We couldn’t make a poster that didn’t include all possibilities. It’s important to note that Silence=Death was meant to be the first in a series of three posters. A second poster, the AIDSGATE poster, drilled deeper into the question of race and misogyny. So I think there are lots of misconceptions about the whiteness of ACT UP, and certainly the majority of the people who attended the Monday night meetings were white. That pushes all of the organizing in other communities to the side. There were aspects of ACT UP picked up by the media that related to image culture and ignored all the other questions that we were raising.

QWEEN JEAN: Thank you for saying that. I know that when I first moved to New York, I spent a lot of time at the Schomburg Center [for Research in Black Culture] and I realized I had no idea about other organizations, in particular folks of color that were also truly being affected at the time, which led to the formation of GMAD, Gay Men of African Descent.

FINKELSTEIN: You’re right. When I saw Marlon Riggs’s documentary Tongues Untied [1989], it completely changed the way I thought about everything. And again, if you’re going by ACT UP as some historical marker, you’re not able to know how much impact ball culture had, for example, on our work. We know that ball culture went back to the early 20th century. It wasn’t invented by Jenny Livingston or Madonna. There’s this constant shed of reevaluations about the historical meaning of the activism in communities of color. And I think when I was working on the Art AIDS America show, the curators, and actually the entire art community was forced to confront the fact that the reason why there were so few artists of color represented in that show was that that show was based on art canons, and art canons are based on Western European hegemonies, which are exclusionary. So I think we’ve just begun to scratch the surface of intersectionality. And the last thing I will say is, the activism coming out of communities of color over the past couple of decades has been amazing. I don’t think people know it was trans women of color who were involved with the original calls to Zuccotti Park that led to Occupy Wall Street. There’s so many ways in which communities of color have inspired us all. We didn’t invent the idea of Silence=Death. Audre Lorde wrote about that. There were so many layers of meaning that we’re just beginning to scratch and I think that thanks to the work of activists of color, I can finally see the world on the horizon that I’ve been hoping for my entire life. And I can’t tell you how that makes me feel. Black women, including Black trans women, should rule the world. Let them rule the fucking world.

QWEEN JEAN: That is the sound bite.

FINKELSTEIN: I curated a bunch of public art installations for Playwrights Horizon. And one of the artists was Dread Scott, who did us the honor of making a text piece. It was billboard sized at street level. And it said, “White people can’t be trusted with power.” He put it on his Instagram and Instagram pulled it down. So he challenged Instagram and then Instagram said, “Well, it was the algorithm, it wasn’t us.” so then he put up a piece saying, “Instagram’s algorithm censored me.” And they took that down. Then the piece was graffitied with Trump stickers. Somebody put Trump stickers across the text. This is the 21st century in New York City. Think about it.

QWEEN JEAN: Censorship is so pervasive. And I think it has permeated our understanding of revolution. There’s always this idea of a bottle cap, right? We can let out only so much and then we have to put a cap on it. We can have only so many leaders of color, and then we’ve got to put a cap on it.

FINKELSTEIN: And we can only hear certain things about race and we can only hear them at a certain volume and they can only come from certain people. I think in terms of queer history that the fact that Stonewall was not the first riot. There was the Cooper Do-nuts riot and the Compton’s Cafeteria riot, those happened, one of them happened a decade before Stonewall. So why is Stonewall the thing, right? I think even with the White Night riots, which were pervasive in San Francisco after Harvey Milk’s assassin got a light sentence, that there is a tendency to tuck queer radicalism to the margins of American resistance. The idea that queers might fight back is super scary, and there’s only room for one queer riot. So it’s Stonewall in New York. It was near the media center, it wasn’t in the Tenderloin. It was in the West Village. There’s so many layers of meaning to it. But knowing our history is so important, and that’s what makes this moment unique, in regards to the history of HIV and AIDS, that we’re in this unique moment where the few people of my generation who survived it can be questioned about it by younger queer activists, historians, artists who are thinking proactively about it. And I think intersectionality is the right way to think about the history of HIV/AIDS. The How To Survive a Plague narrative is one narrative. It’s not untrue. It’s just like the hangnail on the hand of the story.

QWEEN JEAN: Any time people are fighting against systems of oppression, I think there will be folks that want to say, “Well, this is the way that it should be done,” or, “This is the only way that we achieve it.” And that’s not true because there are many, many ways that people have been fighting. People have been inspired to fight for many different reasons. And what I think is powerful is that we’re fighting. We’re fighting. That’s all we need to do.

FINKELSTEIN: Yeah, it scares the crap out of them.

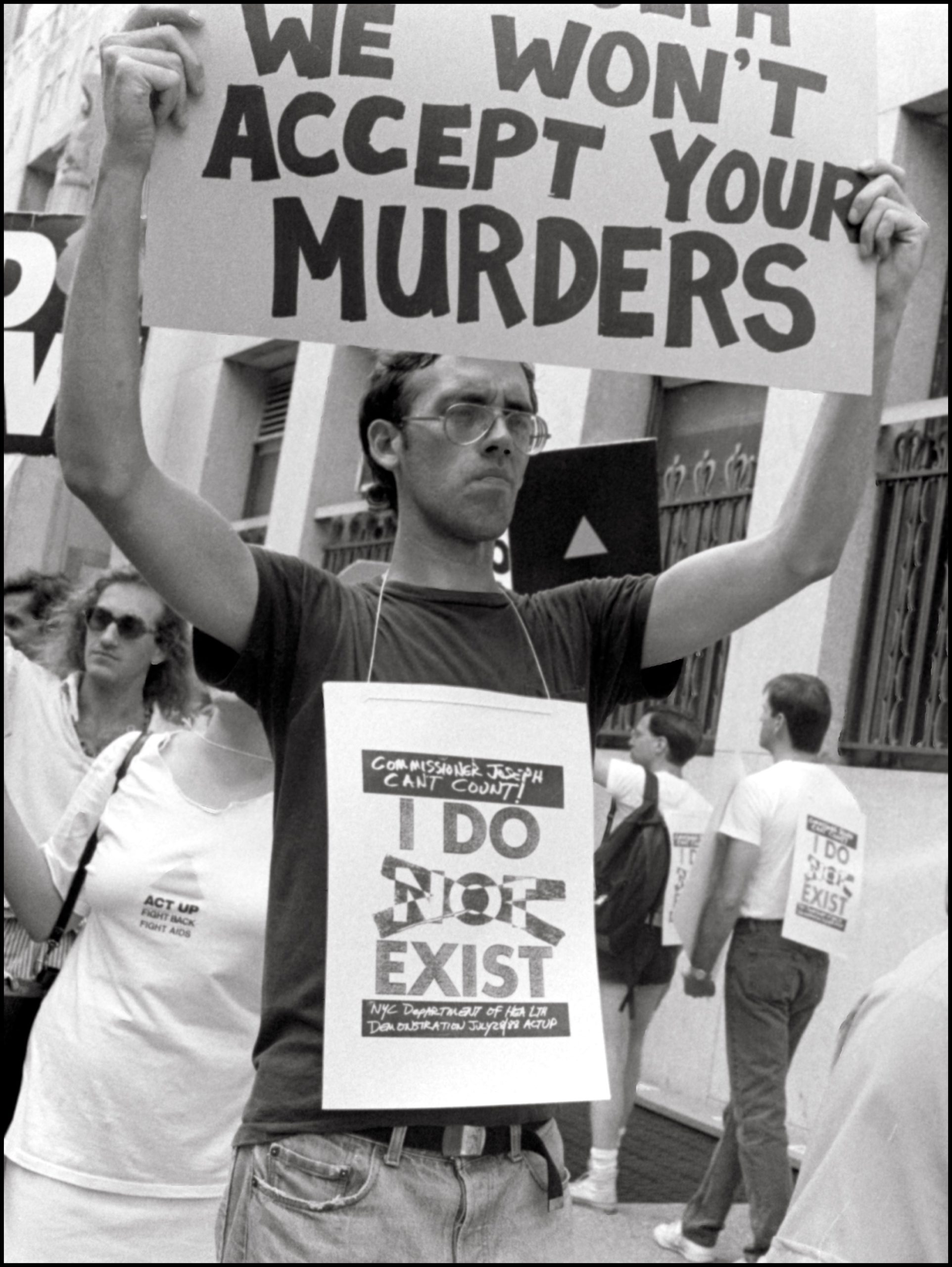

David Wojnarowicz of ACT UP demonstrates outside the offices of the New York City Commissioner of Health, 1988. Photo: t.l.litt ©t.l.litt

QWEEN JEAN: How do you see the crossover between art and activism?

FINKELSTEIN: Language is a high wire act. The question of “artivism,” when people use that phrase as opposed to activism, that can be articulated in multiple ways. Art makers, culture makers or cultural producers or cultural workers are not a privileged class. We don’t have any more to say about the world than someone who drives an Uber. We’re just handed that baton based on hierarchies that are false. And in a way, the joining of art and activism is almost like an act of Balkanization on the part of capitalism. It’s a way of saying, “Okay, well art as activism is productive. Rioting is disruptive. So we’re going to go with artivism.” Look, I’ve said the word riot way too many times and I’m loathe to use it after January 6th. But I do think that radical resistance is very uncomfortable and very unpleasant to power structures. I think artists can be activists, but activists don’t need to be artists. One of the things about Silence=Death, it really functions beautifully in the fact that it still functions and I’m honored to be asked to talk about it. But it also casts this mighty shadow. You feel like in order to change the world you have to have a logo. That’s not true. This is a poster made by six people, right? Anyone can change the world. And for someone reading this interview long after you and I are dead, it might spark an idea that actually changes the world. So the point of these conversations is to float ideas to people who might not feel empowered in their own political agency.

QWEEN JEAN: In terms of art and activism, I often think of that powerful Toni Morrison quote: “There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.” That’s it. In moments of contention and moments of great despair, we have to work. We have to step up. And you have stepped up. You have literally galvanized so many people, and I just wanted to say thank you.

FINKELSTEIN: You’re kind to say that. I think the one thing that I would want young individuals, whether they’re activists or not, to know is that there’s something called plotter paper. It’s the cheapest kind of paper. You can print a mural sized print for 60 dollars. You don’t need funding. Or you can do a little bit of fundraising. You don’t need tons of money to create a billboard. And I think it’s super important that we think expansively about how to articulate our own voices collectively, and as individuals.

QWEEN JEAN: In this idea of progression versus placation, do you think big changes can actually happen and have direct outcomes?

FINKELSTEIN: I think that the entire world needs to change, and I believe we’re in the process of watching that change. I think about the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand at the beginning of the 20th century which caused every war and changed everything about the 20th century. We are in that moment now. What is happening now will define the entire 21st century. Now is the time to do it. Now is the moment.