Harry Dean Stanton on Paris, Texas: For the first time, I got the girl

Harry Dean Stanton is a very late bloomer. Thirty years and 60 films after making his screen debut in a Western doozy called Revolt at Fort Laramie, the 59-year-old actor is finally being offered top billing, spots on David Letterman and other rewards befitting an artist of his tenure. His price has doubled in the last three years and the ranks of his admirers—which have long numbered such close friends as Jack Nicholson, Robert De Niro, and Bob Dylan—have grown to include the Brat Pack actors, led by Sean Penn, Rob Lowe and Emilio Estevez (who co-starred with Stanton in the cult feature, Repo Man). While winning the hearts of these teen heroes, Stanton has at last seized the attention of the most influential movie-going audience in this country.

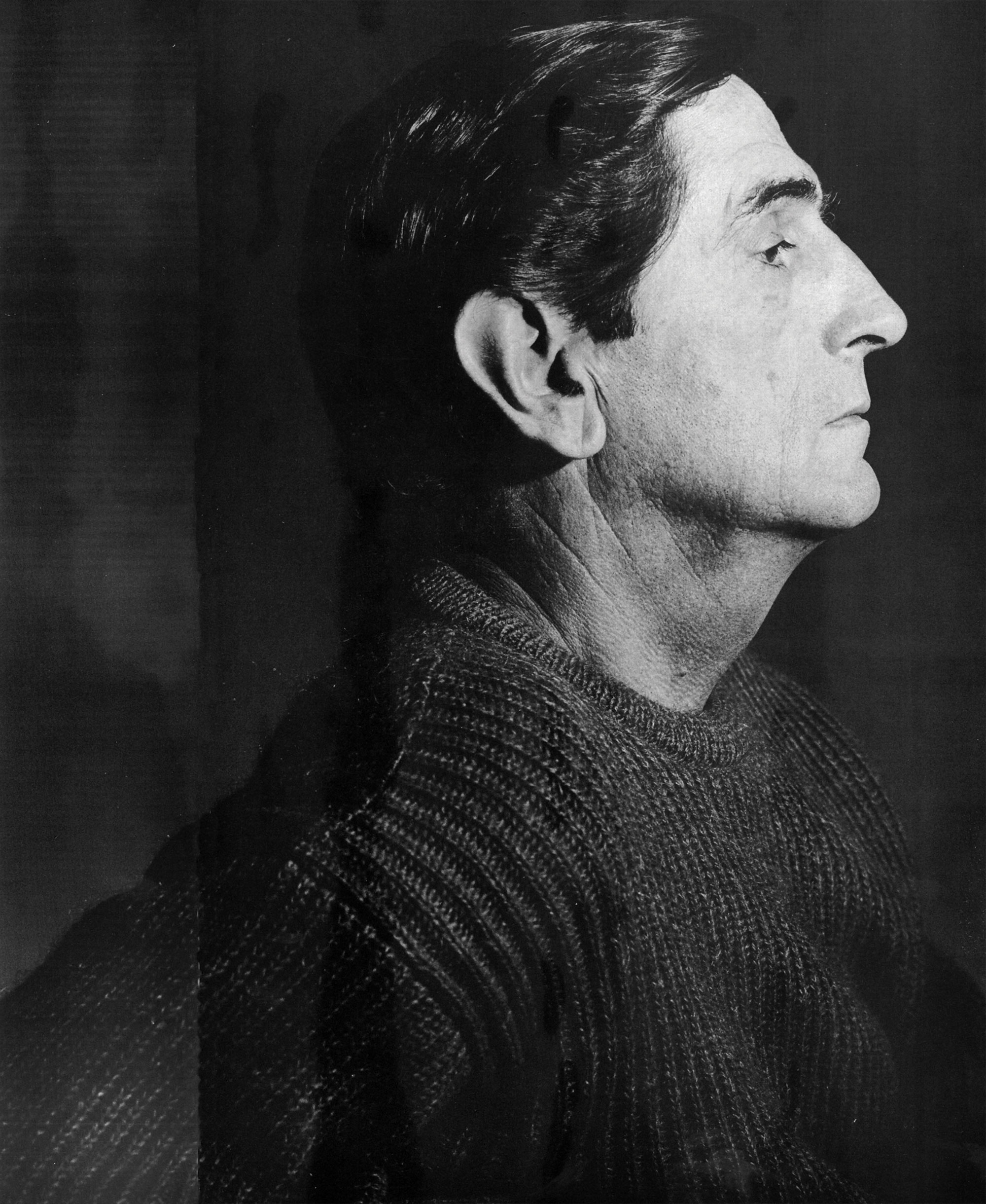

This all sounds rather fortuitous, but as Stanton repeats over and over in conversation, there are no accidents, even in the movies. His personal and professional dues have been paid ten times over and he’s hungry for the overdue attention. “My career was horseshit until a couple of years ago,” says the actor in his soft, lyrical voice. “For the past 30 years, I’ve been in a psychological swamp, wandering in a maze, a victim of my moods. Luck kept me from becoming a total drunk or drug addict.” Stanton’s sad, hound-dog face is a well-tended monument to dissolution, and has everything to do with three decades of typecasting—this, and an air of bleak detachment. And though Stanton claims to be as “good-looking as Dustin Hoffman,” there’s a striking difference: Hoffman looks like family; Stanton is a stranger.

Still, he has never stopped working, playing characters you’d much prefer to forget. He was the outlaw annihilated by Marlon Brando in The Missouri Breaks, an FBI agent in The Godfather, Part II, a ranch hand in Rancho Deluxe, a fake blind preacher in Wise Blood and an ornery country singer in The Rose. Three years ago, Stanton seemed destined to go the way of all actors’ actors: gentle into that good night. Then he met Sam Shepard.

“We had a couple of drinks and I told Sam that I was sick of playing heavies and losers and trash,” says Stanton. “I wanted to play something with some love and decency to it. Sam just listened.” Two weeks later, Shepard called to offer Harry Dean Stanton the first starring role of his career, in Paris, Texas. It was a piece of casting made in heaven, and though the film was completely ignored by the American Academy (it won first prize at Cannes), Paris, Texas marked Stanton’s breakthrough. More than vaulting him to the top of the marquee, it proved a psychological point with which the actor had long been wrestling. “For the first time, I was allowed to get the girl,” says Stanton with emphasis. “That’s such sacred territory in the business, a primitive battle over the female.” No stranger off-screen to beautiful women, Stanton weathered this rite of passage and nothing has been the same since.

Life began for Harry Dean Stanton in a small Kentucky town. The eldest son of an Irish housewife and a father who divided his time between a barbershop and a farm, Stanton carries childhood memories that read like the sad stuff of Flannery O’Connor. His earliest recollection is of his mother giving birth to a stillborn baby girl. “I was there the night it happened,” remembers Stanton. “The radio was playing a song called ‘Roll Along Kentucky Moon.’” Stanton stops speaking, visibly struck by the image. “I think my father buried the baby out in the field. I remember yelling and screaming. Pain.”

Home life never got better. “I reacted strongly to the insensitivity within my own family,” he says. “I was more high-strung and vulnerable than the average.” A musician since childhood, Stanton sang with a barbershop quartet as a teenager, and has sought the company of musicians ever since (to date he’s performed with Bob Dylan, Kris Kristofferson, Linda Ronstadt, Carole King, and Ry Cooder, among others). After a stint in the Navy, he studied for four years at the renowned Pasadena Playhouse and continued to sing around L.A. coffee houses during the 1950s and ’60s.

It’s hard to know why Stanton chose the films he did, instead of holding out for the films he wanted. Partly, it was the drive to work, partly the need to put food on the table. “It’s alright to play a murderer if the script is making a righteous point,” he has said, and this logic led him to accept some of the worst roles ever written (note The Mini-skirt Mob, 1968). Infused with a restless, beatnik spirit, Stanton used acting as a way to keep wandering. He read Emerson, Alan Watts, Krishnamurti and the I Ching in search of emotional peace. “I was a man full of rage, which is why I attracted hostile roles,” he says. Like many angry men, Stanton became a womanizer bent on”conquering anything that walked,” and, except for a two-year relationship with actress Maggy Bly in the ‘’60s, and his on-again-off-again dedication to Rebecca De Mornay, Stanton’s reputation as an alleycat is untarnished. In typical fashion, he arrived at Madonna’s wedding this summer with a Playboy bunny in tow.

These days, even his attitude toward the opposite sex has become more civilized. “The more I’ve mellowed the more women have become attracted to me,” says Stanton, whose taste runs toward the nubile. “I’d gladly marry a woman 30 years younger than I am. I feel more comfortable with people in their ’20s than with people my own age. There’s less bullshit, and I have a tremendous amount of energy.” Confidante Lois Chiles calls him the most “in-the-moment” man she’s ever met.

Life’s payoffs, it seems, have arrived in plenty of time for Harry Dean Stanton, and plenty of time for Harry Dean Stanton, and next year at this time—barring unforetold disaster—his name will finally be as well known as his face. With leading roles in Paramount’s Pretty in Pink and Disney’s Father Christmas on the way, Stanton will receive widespread recognition this month as Sam Shepard’s on-screen father in Fool For Love. “I feel closer than ever before to what I’ve always wanted,” says the actor. In a conscious effort to soften his image, he recently turned down a psycho role in Miami Vice—a move he’d hardly have dared to make ten years ago. In the shadow of his 60th birthday, Stanton is on the brink of stardom and watching his every step. “Age is a tremendous prejudice,” he says. “I want to die young.”