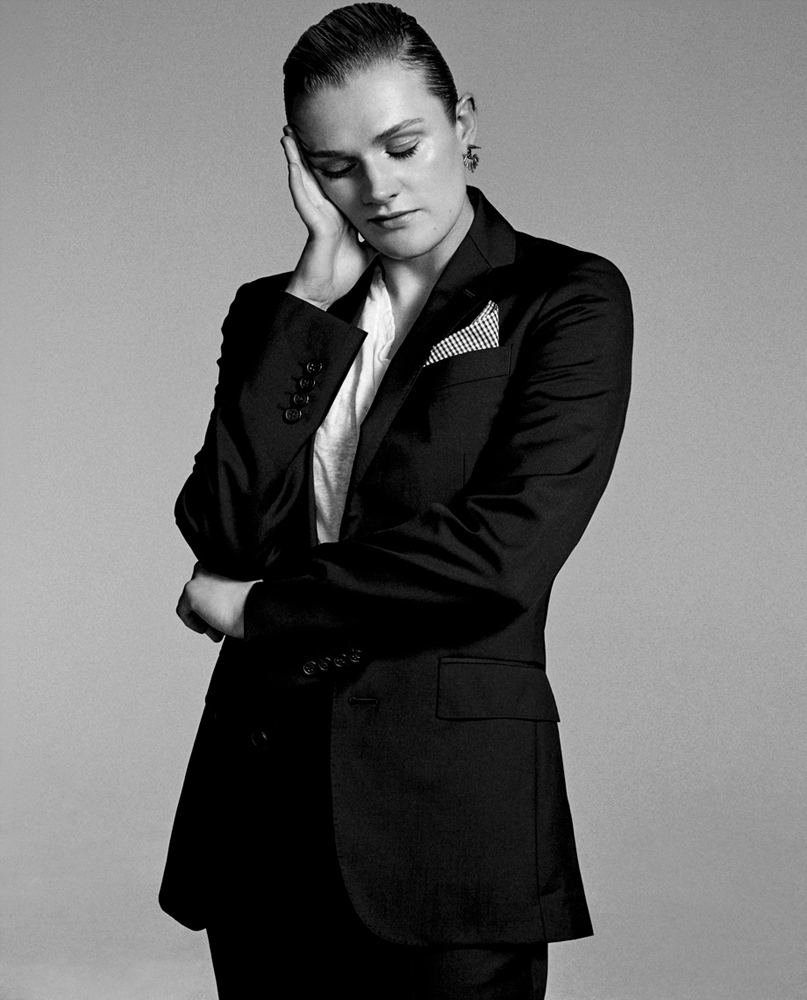

Gayle Rankin on Method and Madness

GAYLE RANKIN IN NEW YORK, JUNE 2017. PHOTOS: MICHAEL SCHWARTZ. STYLING: JOSHUA LIEBMAN/HONEY ARTISTS. HAIR: MARTIN-CHRISTOPHER HARPER FOR PLATFORM|NYC USING VERB. MAKEUP: HOLLY GOWERS FOR ATELIER MANAGEMENT USING GLOSSIER. PHOTO ASSISTANT: AMANDA YANEZ. SPECIAL THANKS: DUNE STUDIOS.

Some 400 years after her creation, there’s little that can be said about Ophelia that hasn’t already been said before. As the doomed ingénue of Hamlet, Shakespeare’s eternal tragedy, she has fascinated generations of directors, actors, writers, artists, and viewers, who cast onto her their hopes, values, and frustrations. Throughout history, her representations on stage have changed wildly according to the dominant theories and images of female identity, despair, and insanity. Some see her as a feminist hero, others as a victim exploited. The challenge of stepping into a role so entrenched in theatrical lore is one 27-year-old actress Gayle Rankin embraced head-on. In a new production at the Public Theater, directed by Tony Award-winner Sam Gold (A Dolls House, Part 2; The Glass Menagerie) and starring Oscar Isaac in the title role, Rankin sinks her teeth into the misunderstood heroine, and attempts to imbue her with genuine life.

The Scottish-born, Julliard-educated Rankin made her debut in the Alan Cumming-led Broadway revival of Cabaret in 2014, as the prostitute Fraulein Kost. Last summer she starred in the Public’s all-female Taming of the Shrew. More recently, she has taken a turn from the stage and into the helter-skelter world of 1980s female professional wresting, in the new Netflix series Glow. In that, she plays Sheila, a woman who has species dysmorphia and believes she’s a wolf. In the fall, she will appear alongside Dustin Hoffman and Ben Stiller in Noah Baumbach‘s The Meyerowitz Stories.

Ahead of Hamlet‘s official opening tomorrow, we met up with Rankin at the Public to discuss deliciously flawed characters.

MATT MULLEN: What were your initial reactions when Sam Gold approached you for the role?

GAYLE RANKIN: It was surprising, first of all. Sam and I have known each other for a long time. We’ve worked together, we’re friends, we both went to Juilliard—though not at the same time. I was having a really shitty pilot season in L.A., and Sam called me out of the blue and said, “Would you like to do Hamlet with Oscar Isaac?” And I was like, “Is that an … offer?” Like are you serious? I’ve never experienced that in my life. It’s the biggest, most generous gift I’ve ever been given from a collaborator, to have someone trust you with this role. It was intimidating, but I think the best decision that I made was to not—literally and figuratively, over time—overthink it, overwork it. What’s so amazing about how Sam approaches Shakespeare is that we work really hard and really specifically and really rigorously on the script, on the text, but then at a certain point he asks us to throw that away and to play the scenes and the moment with who we are that day or that night. That’s what makes his work sing. People come see it and it’s like, “Wow, it’s so casual, it’s so you guys, it’s so real.” Yeah, because it’s kind of really happening every night. That’s what we’re really trying to do.

MULLEN: I know you said you didn’t want to get intimidated, but I have to ask, the role of Ophelia is such a difficult role.

RANKIN: I’m still struggling with it.

MULLEN: Can you tell me about that?

RANKIN: I think what’s hard is I was both really interested in having a take on her, but I also get very upset when people try to reinvent the wheel for the sake of reinventing the wheel. I don’t enjoy watching plays where clearly a hat has been put on a hat. It was intimidating because I was aware that I wanted to make her strong and I wanted to make her not weak, and I wanted to make her into me and every woman today in 2017, but also not change the story. And the story is that she doesn’t make it. This is something Sam and I were literally just talking about in rehearsal an hour ago, which is that it’s a hard journey for me to go on because she doesn’t make it. Some nights I don’t want to, or I want to fight a little bit more for her. But leaning into what happens to her is really important and it’s really important in our production. The decision to end her life is not one that I think is weak. It’s not strong necessarily, but it’s not weak. That’s why it’s a tragedy.

MULLEN: How did you relate to the character? How did you prepare?

RANKIN: We first did a workshop about a year ago. Me, Keegan-Michael [Key], Oscar [Isaacs], Matt [Saldívar], Anatol [Yusef], and Ernst [Reijseger], who was doing music, were part of it. Then I was shooting Glow in between this and the workshop, and I think that was really healthy for me. And then I spent a month in Connecticut with my boyfriend. He’s a filmmaker, so he was working on something, and I was working on Hamlet, and we were both just in our secluded art retreat. I like to build a foundation of touchstones. I don’t know what’s going to come to me when I’m building a character. Weirdly in this process, I started to think about drawing. And I don’t draw. But I started seeing images of me playing Ophelia in my head. And that posture or that image or where she is placed on the stage in my head, I don’t know why it came to me when I was thinking of this, but I felt like I needed to draw it.

MULLEN: Given that it’s Hamlet, there is no shortage of influences to look to. Did you look to any past performances or adaptations? Or was there anything you had seen that you knew you didn’t want to do here?

RANKIN: Yes, sure. I have strong opinions about what I don’t want to do. [laughs] Generally I love to seclude myself from other adaptations; I won’t necessarily watch all the Hamlets, or I won’t read about the Hamlets. I like to try and create a bubble for myself, healthy or not. But one thing I knew I didn’t want to do was the madness aspect. And I hate that word. I struggle with it so much. There’s no madness. There’s feigning madness, but these people are not mad. They are destroyed. They’re decimated. They’re grieving. That can look like madness. So I really didn’t want to play general madness. I felt very responsible to be delicate about framing the logic of what happens in those mad scenes.

MULLEN: Was finding that logic hard?

RANKIN: Yes—very hard. But it’s there. She speaks in nonsense, and she sings, but why does she sing? I didn’t want it to be like some la-la-la crazy girl singing her song. I wanted to make it active and purposeful. I wasn’t interested in having her be waif-y or flighty or general. I wanted to figure out why does she sing, “How should I your true love know from another one?” She sings it because she’s really asking the question. Like “How should I know someone that loves me from someone who doesn’t love me, because if someone that I thought loved me did this, then what is love?” The reason she kills herself is because the world has proven to her that love doesn’t exist. I get that, I understand why she’s like “Well, what’s the point? If love doesn’t exist, what’s the point?”

MULLEN: There are many feminist interpretations of Ophelia. Did any of that inform you or your development?

RANKIN: No. Again, I was super wary of… well, I read the book Reviving Ophelia, which is an incredible book and everyone should read it. Especially anyone who is a woman and has children who are women. That was super informative and helpful. But that’s it. I didn’t want it to be a political statement. You know, and it’s hard not to make things a political statement.

MULLEN: What was the rehearsal process like?

RANKIN: Really fun, number one, which is weird. We played a lot of ping-pong, because we had a table. There were a lot of rehearsals that were intense and grueling, but there was lightness there. I think we had to gravitate towards light when working on something so dark, and it wasn’t even conscious, we were just kind of craving it. And when you’re hanging out with Keegan-Michael Key it’s going to be fun. [laughs] Once we got on our feet, there was a lot of time spent trying to figure out how to work in the space because Sam’s plays require everyone’s creativity to make the space work. Because it’s not necessarily specific. It’s not like you’re in 1600s Denmark. We’re not in Denmark. We’re in New York City in the Anspacher [theater]. The chairs are the same. So what’s that vocabulary? What does the lasagna mean? Where did the lasagna come from? Did we order it from Lafayette?

MULLEN: What was your childhood like?

RANKIN: It was lovely. I grew up definitely in what you would call the countryside, outside of Glasgow. I didn’t speak for like three years of my life. I was a very quiet child, which I think translates into a big part of me, of who I am now too. I was just talking to someone else about this the other day. I’m an extroverted introvert. I think. I have extremely supportive parents. My mom was obsessed with old movies so I watched them with her, and she has really amazing taste in music. So I was exposed to art young, but not necessarily plays. Then when I was about seven or eight I expressed interest in wanting to sing and my mom was like, “Of course, we’ll try and find you a singing teacher.” And then we went to the singing teacher and she was like, “Gayle’s a little young,” and mom was like, “I know, but she really wants to do it.” So they’ve never pushed me, it’s only ever been supportive.

MULLEN: What was your early relationship with Shakespeare like, when you were a kid?

RANKIN: The Scottish Opera runs a children’s acting program, so I went there for a while when I was young. I remember doing a production of Mac… the Scottish Play, rather, when I was young there. That was my first exposure to Shakespeare—they’re not afraid really of exposing young kids to it. But until Juilliard I wasn’t really in it, in it. Eventually Shakespeare became one of my favorite playwrights, but I was way more into the Russians when I was at school. Chekov and all those.

HAMLET IS NOW ON AT THE PUBLIC THEATER THROUGH SEPTEMBER 3.