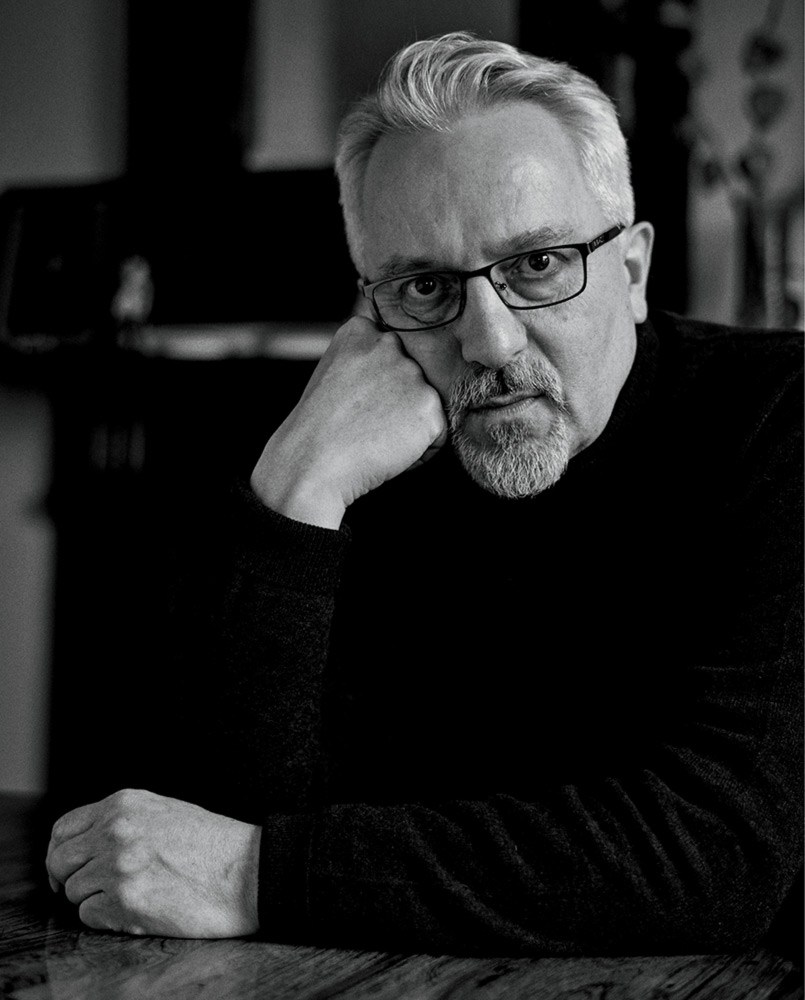

Gay lit icon Alan Hollinghurst on scandal, repression, and British life

An Alan Hollinghurst novel comes into the world with a whole heart. There’s so much honest living going on in his pages—desires, needs, regrets, sex, worries, beauty, ugliness, anxiety, humor—that the 63-year-old British author is arguably the finest coiner of character at work today. Hollinghurst started out as a poet, and that attention to sound and imagery can be found in every one of his famously gorgeous sentences. In fact, his prose is such a come-on, you can easily be seduced into forgetting that his subjects tend to punch with politics and radical social critique. (If he’s a descendant of Henry James and E.M. Forster, he’s also one of Jean Genet and Edmund White.) His first novel, 1988’s The Swimming-Pool Library, about a young, handsome neo-dandy in ’80s London, is perhaps the best modern novel about urban gay life, and it established Hollinghurst as a master at describing so richly what so many others would have turned away from in fear. His fourth novel, 2004’s The Line of Beauty, about a much more inexperienced young gay man growing up in a world of privilege, Thatcherism, and AIDS, is an epic portrait of a whole pretty era going off the rails.

In his sixth and latest novel, The Sparsholt Affair, Hollinghurst takes aim at nearly a century of gay life in Britain, beginning in Oxford just after the start of World War II, with German planes obliterating parts of London, and ending in the present in a gay universe of dating apps and raising children. If the presiding symbol of The Swimming-Pool Library was the buried, the underground, or the submerged, and if in The Line of Beauty it was the watery, double S-curve after which the book takes its name, for The Sparsholt Affair the symbol is the frame.

Throughout the novel, Hollinghurst changes the framing devices of his story, from first person to third, from father to son, from one decade to its opposite, from the subject of paintings, photos, and rumors, to the professional portrait painter setting his sitters down into permanence.

At the center of the story is the mysterious, handsome, and possibly bisexual David Sparsholt, who appears in the dorms of Oxford University from a working-class industrial town and quickly attracts the attention of the young, cultivated aesthetes who pine for him. We then jump forward in time to David’s son, Johnny, on family holiday, himself pining for a wily French exchange student. Eventually, after another time jump, there is mention of a sex scandal involving Sparsholt Senior that has tarnished his reputation and wrecked his marriage, and it isn’t long before we follow Johnny, an ambitious portrait painter, into a fully realized gay life that would have been denied to his father. Hollinghurst writes some of his best lines about love, loss, and memory in this novel, describing a character’s loneliness as “like an ache in his arms” and capturing the strange familiarity of waking up in one’s childhood bedroom after so many decades away and hearing “the noise of doors downstairs, never thought of, never forgotten.” I met up with Hollinghurst this past December in London, and we talked over coffee at a hotel in Marylebone.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: I spent the day at the National Portrait Gallery and at the Wallace Collection. Somewhere in those galleries, it dawned on me that you are the writer equivalent of a portrait painter. Of course, one of the protagonists in your new novel really is a portrait painter. But what I mean is that you have a great gift for giving a character so much shade and depth, soul and flesh. Do you see any connection to portrait painting in what you do?

ALAN HOLLINGHURST: Portraits do interest me. I must say, when I’ve had some spare cash, I’ve found myself collecting them. Since I don’t have much space at home, they are rather small ones, and they tend to be of people I don’t know anything about, so everything is conjecture, really.

BOLLEN: You actually go to auction houses and hunt around the sales?

HOLLINGHURST: Well, I became really addicted about ten years ago, when I discovered that auction houses put all their catalogs online. People get addicted to various things online. My addiction is relatively harmless.

BOLLEN: Is there a particular period to which you’re drawn?

HOLLINGHURST: The period between 1880 and 1920. I’m interested in the school of Whistler in this country, where an American artist comes here and paints extraordinary, radical works, and people catch onto it, with this whole realm of imitators. It was fascinating to discover a labyrinth of minor artists that I can afford. I’ve rarely spent more than 5,000 pounds on them and generally much less.

BOLLEN: Most portraiture subjects are wealthy. You had to have means in order to commission the artist. In the last section of your new novel, your main character, Johnny, is painting a very wealthy family at their suburban mansion.

HOLLINGHURST: I was trying to poke a stick at that notion of these rich people who commission an enormous family portrait with them sitting in front of their marble fireplace and their Labradors just as a way of showing themselves off to the public. It’s saying all sorts of things about these people, which they themselves can’t possibly understand. The latent ambiguities that are hidden in portraits are so interesting. And is it good art in the end? I was quite intrigued by that aspect of portraiture, too. How much truth-telling can you get away with in something that is essentially designed to flatter the subject?

BOLLEN: When you go about building a character, how much detail comes into your head right away? Do your characters tend to reveal themselves to you all at once?

HOLLINGHURST: I usually end up giving just a few little physical details, which encourage the reader to make up the character themselves. You could have a sort of Dickensian approach, where you get almost grotesquely detailed with an exaggerated sense of someone’s physical appearance. But I think for a lot of the great fictional characters, you might only know roughly how tall they are or what color their hair is, or perhaps their eyes might be rather significant. Oddly, I think it’s the lesser characters that you might describe more vividly because they only get one moment in the spotlight. But I build a lot of characters more out of what they say and perhaps the way that they say it—the mannerisms and gestures associated with speech, as well as the tones. I’ve always been interested in analyzing the way people say things and what they’re not saying or trying to conceal.

BOLLEN: I don’t think of you as a minimalist when it comes to physical description. When I think of all of the bodies that inhabit The Swimming-Pool Library, for example, each one was so richly depicted. Maybe that’s simply because there was so much sex and nudity at the core of the novel. Do you gravitate to scenes that have a sexual frisson?

HOLLINGHURST: I used to think so. Perhaps more than I do now, which is maybe why I write fewer of them. In terms of The Swimming-Pool Library, it was such an exciting thing to be writing about in the first place back in the mid-’80s. I was writing about life—and sex life—from the point of view of a young gay man who is quite sexy himself.

BOLLEN: That was the first book I read of yours, and it blew me away. I was reading it from the vantage point of the 21st century, and it still felt full of risks and exciting complications. What was the response when it was published in 1988? I don’t think there’s been another book that has captured being a young gay man so vividly, before or since. What was your feeling when it was released?

HOLLINGHURST: It was complicated. I felt confident in it. I felt I’d done what I wanted to do, and the book was as good as I could make it, so I didn’t have those sorts of worries. But there was quite a lot of anxiety. I was 33 years old when it came out. I’d sold the world rights to Chatto & Windus for 5,000 pounds. I consulted with a high-powered agent beforehand, and they said, “Take that deal. I certainly couldn’t do any better for you. There’s no way I could sell this book in America.” [Bollen laughs] It came out when there was a lot of worry and fuss because of Clause 28 over here. The government was pushing through this local government bill, which had a clause that forbade spending money on anything that promoted homosexuality. So there was a lot of talk about public libraries possibly being unable to stock my first novel. Did The Swimming-Pool Library promote homosexuality? I think it gave a rather terrifying picture of it. [laughs] But it was so typical of the ethos of those years, the idea that if you promoted homosexuality successfully with a big campaign, it might really catch on and everyone would be gay. There were lots of protests and demonstrations against Clause 28. I suppose it was all part of the complicated reactions to the onset of the AIDS crisis. It’s hard to reenter the atmosphere of that period now. If someone is reading that book for the first time today, they’re reading it in such an amazingly changed world. But part of the excitement of writing that book for me was that it was something new. I loved writing it. There was that innocence of writing a first book where no one knows anything about what you’re up to, and you have a full-time job, so you write at home in the evenings.

BOLLEN: Were there any literary influences or predecessors you were thinking of when you were writing it?

HOLLINGHURST: Edmund White’s A Boy’s Own Story had been very important to me, being both incredibly, beautifully rich and so unprecedentedly candid. But there hadn’t really been anything of that kind in this country. Of course, the legal situation was odd then. You know, we’ve been marking the 50th anniversary of another act, the Sexual Offences Act.

BOLLEN: Right, in 1967.

HOLLINGHURST: Yes, the year homosexuality was decriminalized in England and Wales. That was when the law changed, although attitudes always change more slowly. My first novel came out 21 years later, and I think it was the first literary novel in this country to be open about gay life. So I just felt like I had this amazing opportunity to expose the subject.

BOLLEN: I’m thankful we had Ed White in the United States to clear a path. I’ve often wondered about the differences in gay culture between America and Britain.

HOLLINGHURST: The cultures are different. They were both repressive, but they had different legal situations. Up until I was 13, homosexual acts were illegal in this country, which the plot of The Swimming-Pool Library very much turned on; these desires, which were being acted on so unthinkingly by the narrator in the present, had long been severely punishable. That was a subject I’d worked on as a graduate student at Oxford, looking at writers like E.M. Forster, who hadn’t been able to write openly in their lifetimes about their sexuality. Do you think there’s a difference?

BOLLEN: I think there are two different archetypal gay-male stories. In America, it’s lonely cowboys experimenting in nature. In Britain, the sexual experimentation always seems to happen at boarding schools. In America, we don’t really have that culture of homosexual permissiveness at school—which is not to say it doesn’t happen. But in Britain, it seems such a part of school life. In The Sparsholt Affair, you capture the way it sort of bounces around direct mention at Oxford in the 1940s.

HOLLINGHURST: That might be a class thing, but there was indeed a gay culture in boys’ boarding schools or public schools. For this book, I wanted to get that slightly odd feeling of wartime that can lead to disinhibition. You know, “This could be our last night alive so you better—”

BOLLEN: “Do whatever you want.”

HOLLINGHURST: And the lights were all turned off on account of the Blitz, so I wanted to re-create that rather exceptional atmosphere. But you’re right. With the social world of public school types, these things are sort of accepted, particularly when you’re young, and in a way that they’re not when you’re out in the rough-and-tumble real world. I really enjoyed writing about Oxford at this strange moment of war because of the extraordinary conditions. I didn’t want to write an idealized version of Oxford, like a terrible, hackneyed kind of Brideshead Revisited. Those years seemed a fascinating moment when people of different backgrounds might have just been thrust together there in a new way.

BOLLEN: Especially when you’re facing possible doom for the first time. The idea that the world is blowing up and there might not be a future could perhaps symbolize everyone’s college years, but for these characters, they can actually see the bombs dropping on the horizon.

HOLLINGHURST: Normally, as an undergraduate at Oxford, you have this sense of three or four years of a leisurely stretch ahead of you, but back then most people knew they were going to go up for probably only a year before they were going to be drafted and sent to who knew where.

BOLLEN: The Sparsholt Affair isn’t your first novel to encompass such an expansive amount of time. People always mention the difficulties of writing about the past. But I often wonder if it’s harder to describe the present. Sometimes you have to remember to put cellphones in your characters’ hands or give them Instagram accounts. Are you more comfortable in the past or the present?

HOLLINGHURST: With my previous book The Stranger’s Child, which starts in 1913 and ends just the other day, I’d imagined that the later parts would be easier because they happened during my own lifetime. But actually I found them much harder to write. That might be because there is so much material and overabundant detail that you have to filter out. It comes down to the whole essential business of selection, which is what writing is about, really. And there’s also the fact that I seem to be drawn back into periods of the past. Particularly if I’m writing about gay life, the questions are more complicated in a world in which things had to be secret and coded. That lends another dimension of interest and excitement. I’m not saying that I don’t very much prefer to live in the present world, but I do find it somehow slightly less nutritious as a writer.

BOLLEN: I agree. Liberation is what we want, undeniably, but good stories often come out of restriction, subversion, and secrecy. In the new novel, the present and past do line up for comparison at certain moments. There are two scenes at gay clubs separated by some 40 years—both are wonderful studies of their era.

HOLLINGHURST: I enjoyed writing those. It was great fun to write the one set in 1974, which mirrored my first terrifying adventures into that kind of gay club in London in the late ’70s. Again, it’s all the slow thaw after the change in the law. If you look at books about London nightlife before 1967, they can’t really say anything explicit about where to go—they would just use peculiar terms like “attractive crowd.” And for so many of these establishments, you had to be a member. I can remember lodging with some parents of a friend at the time, thinking, “Shit, I’ll have to give a completely false address to join.” Then, there was this absurd mandate in the licensing of such a club where they had to serve a meal. [laughs]

BOLLEN: I loved that detail in the book. They’re at a gay club cruising, and they’re suddenly served sad bowls of salad.

HOLLINGHURST: It’s completely true. You had to have some kind of dining license with dancing. Halfway through the evening, you’d look at tables littered with salad debris.

BOLLEN: It’s so hard to write good nightclub scenes or party scenes, mostly because it’s much easier to tackle dialogue between two people than a whole obstacle course of humans. I was recently re-reading a pitch-perfect party scene that appears early on in The Line of Beauty where Nick gets drunk with his friends at a country estate and is trying to pick up a cater waiter.

HOLLINGHURST: I always like writing party scenes. One of the things about it is everybody is saying and doing things they might not otherwise say or do, which they might or might not regret. The Line of Beauty was really one party scene after another. It seemed to be a good way of writing about that period with all this competitive hospitality and ostentation. And just technically, for writing, a party is a very good way to bring everyone together and let you observe them at the same time. They usually have a comic ingredient. But I’ve always enjoyed doing them. You have to keep a guest list beside you on the desk to remind you, “We haven’t seen much of so-and-so for a few minutes.”

BOLLEN: At the heart of the new novel is a scandal. If I’d read this last year, I might have pronounced that the age of the sex scandal was over, but clearly it is not. David Sparsholt is at the heart of your story, and yet he remains a mystery. The reader never fully comes to know him. We learn more about his effect on the other characters. And that’s true for the scandal itself. We know he’s caught up in something, but we never learn the details. I was curious about your decision to keep the affair oblique.

HOLLINGHURST: When I first handed the book in, there was even less about it than there is now. There are scandals in every culture, but I was thinking particularly about the scandals in the ’60s and ’70s in England. In my book, we don’t learn about David’s particular scandal until eight years after it’s happened, and by that time you tend to remember one or two things about it—usually a name. They take the name from the hero or antihero. The most obvious example is the Profumo Affair.

BOLLEN: Was that your template for this?

HOLLINGHURST: Not really, because that was a much bigger thing that threatened a whole government. But I wanted it to have a sexual element, and there’s some sort of element of corruption to do with local government planning and this building project that David is involved with. I haven’t the faintest idea what actually happened. [both laugh] When someone asked Henry James what the woman in his story “In the Cage” had done, he said he didn’t know. He said he would rather not know. I just wanted to have a sad, lingering, dwelling effect of a scandal in the past. And when you mention the name, it brings back this whole tawdry atmosphere. Like Profumo, which is such an unusual name. That’s one reason I chose this unusual name, Sparsholt, so that eight years afterward, when the son turns up in London and introduces himself, people do a double take.

BOLLEN: Scandals erupt in several of your books. It’s a moment where the private and the public really meet. The doors and windows are blown wide for everyone on the street to peer through.

HOLLINGHURST: I’m interested in the private life. I don’t think of myself as a public novelist. Although there are important social and historical legal matters affecting the narrative of the books, which often turn around important dates like 1967 or the great upheavals of the Thatcher years or the great gay purge in the mid-’50s, I’m not terribly interested in writing about those things in themselves, but rather in their effects on the characters. And that’s the same for this book. I’m writing about how the scandal affects the intimate lives of these people.

BOLLEN: I liked the way much was left unexplained. I think there’s a tendency to treat the reader as an infant who must be spoon-fed everything, because heaven forbid they do any work on their own.

HOLLINGHURST: So much in one’s experience of life is unresolved, so I feel interested in creating narratives that don’t tie up in expectedly neat ways. They’re open-ended. At the end, you think, “What did happen?” The characters themselves may not know, and you’re not going to know either.

BOLLEN: In America right now, we have this whole literary, artistic debate about whether one has the right to write about the lives of others. Does a white person have the right to write about a black person? There have been a number of terrific and very complex black male characters in your novels. Do you think writers should only pull from their own background for fear of illegitimate appropriation?

HOLLINGHURST: Absolutely not. It really strikes at the core of what I consider to be the point of writing, which is to imagine the lives of all kinds of people. Some kind of terrible prohibition on writing about people just because they have a different cultural experience from oneself would be a pitiful limitation of fiction. I can see the potential for these things to go wrong for people who don’t know anything about the background—a white writer not knowing about the background of people from the Middle East but presuming to write about it—yes, there could be something offensive in their laziness or their misapprehension about it. So it’s got to be done properly. I haven’t written anything from the point of view of black characters, although they’ve played an important part in several of my books. But I have felt it was important to get everything right.

BOLLEN: There’s a character at the beginning of this novel whose father is a famous British writer. Seventy years later, he’s all but forgotten, a footnote in literary history. I’ve often wondered if fiction writing really is a lifetime profession. Maybe one has two or three books in them and then they should move on to woodworking or flower arranging. But you have built a career from fiction, and a legacy. You’re one of our greats. Does the career and literary position of Alan Hollinghurst ever creep up on you and make decisions about what you write?

HOLLINGHURST: It sounds sort of falsely modest, but it really doesn’t. Part of the point of writing about the preposterous Dax figure is to say how ridiculous it is to have such a regard for your legacy. One of the many things you can do nothing about is what happens to you after you die. I’ve never had a strong sense of a career. I’ve certainly had a similar feeling to the one you just described. When I was beginning Sparsholt, I thought, “Well, I’m 60. Why don’t I just retire?” But partly the reason I didn’t is that I realized I would probably be miserable with my habit of storing things up and holding thoughts in my mind, seeing them as parts of a potential book and having nowhere to put them. It’s very deep in me, so I can’t imagine happily letting that go. I used to have a little voice-activated tape recorder that I’d murmur into suspiciously in cafés. I have a collection of tapes from 25 years ago of me panting along on walks, suddenly confiding some brilliant thought to my tape recorder.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN IS INTERVIEW’S EDITOR AT LARGE. HIS NOVEL THE DESTROYERS CAME OUT IN 2017.