The Birth of Bond

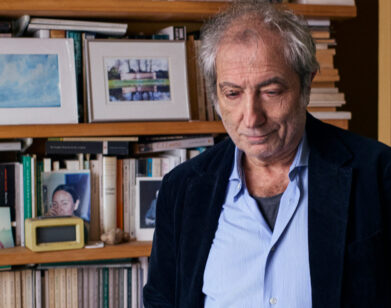

ABOVE: DOMINIC COOPER IN FLEMING. PHOTO COURTESY OF MATT HOLYOAK AND BBC AMERICA.

Dominic Cooper doesn’t remember the first James Bond film he saw, but he remembers the car. “I think it was an underwater Lotus,” he tells us over the phone. “I loved the gadgetry,” he continues. “I remember being influenced by the style of Roger Moore’s James Bond, and later on revisiting the Sean Connery ones and loving them.”

Fleming, Cooper’s new BBC miniseries based on the life of the creator of 007, is both a return to the over-the-top glamour of the Bond films of old, and something with enough emotional grit to resonate with modern audiences. When we meet Ian Fleming in the first episode, he is something of a bounder: an aimless man about town who seduces beautiful women, gets drunk over gourmet lunches, lives in a palatial flat, and disappoints his aristocratic mother. He is not, however, coated in the same static gloss as the character of James Bond was on film before Daniel Craig. Rather, the author is portrayed as proud, passionate, and ambitious in spite of himself.

The series focuses on Fleming’s adult years: from his unsuccessful stint as a stockbroker, to his introduction into Naval Intelligence during the Second World War, to his unfortunate marriage to his longtime lover, Anne Charteris. “It was actually the War and the opportunity to safely be part of the war effort that opened up his imagination and led him on to be a writer,” explains Cooper. While the author’s life was certainly exciting—during the War he was responsible for devising what seem like ludicrous schemes to trick the Germans with names like “The Trout Memo” and “Operation Ruthless”—it was not particularly happy. He broke off his engagement with his first love at the behest of his family, lost his second love during the War, had numerous affairs, and died of a heart attack at age 53. His only son, Caspar Fleming, took his own life at the age of 23. As Cooper notes, “He never really found himself, or who he wanted to be.”

We spoke with Cooper, who is currently filming World of Warcraft in Vancouver, about Fleming the man and Fleming the character.

EMMA BROWN: In the last seven years, the Bond films have gotten quite a bit darker. Do you think that Fleming is a return to the more playful style of the earlier movies?

DOMINIC COOPER: I think so. We’re more at liberty to do it, because we’re using the past and we’re using Ian Fleming as our hero. I think the Bond franchise—it had to get more dark. With the emergence of the Bourne series—the Bourne franchise—I think it had to reach a different level. It couldn’t be so tongue-in-cheek, because we became more aware of that world—it became more realistic. We heard more reports of undercover security missions infiltrating terrorist cells. The viewers needed it to be more embedded in reality. And that’s why the producers of the Bond franchise are so clever. They’ve constantly changed it with the times—it’s been ahead of the times. They’ve been very courageous and daring with their decisions to never keep it the same or as it was. Because we were using the author and the origins of the story, I think we could be very playful with where he came up with the characters and the storylines.

BROWN: Some of the plans Fleming devised when he worked for the Navy seem like they might as well have been fictional— they’re pretty ridiculous. What is your favorite plot?

COOPER: I think the idea of placing a dead pilot in the war zone with the fake documentation on him. The fact that that did have an impact on the war: the Germans changed their attack when they found that body with the information suggesting that the Allied attack would be elsewhere. Fleming was a man who was so forward-thinking.

BROWN: In previous interviews, you’ve said that Fleming is more a portrayal of how Ian Fleming would have liked to be seen, more than how he actually was.

COOPER: I think he was a very complex, dark man who, from what I can gather, wasn’t particularly happy. But he was this very suave gentleman—he was a great charmer and had many, many female partners, was very extravagant, and great fun to be around. He was a great storyteller and probably someone who you’d have a very interesting evening with. But I don’t think he achieved his goals. I don’t think that he believed in himself as a writer, and I think he was always affected by the fact that his mother was disappointed in him. So when I say that, I think I probably mean it was an idea of himself as a man who was much more comfortable in his own skin and enjoyed his life.

BROWN: I was always under the impression that James Bond was based on Ian Fleming’s brother Peter Fleming, rather than Ian’s own personal experiences. I’m not sure I feel that way after watching Fleming.

COOPER: You’re probably right in that it was more his brother. There’s a scene we have where the brother and I sit together at the bar, and Fleming is very interested in what it must be like to kill a man. He knows his brother has done it. I think that that side of James Bond is his brother, because Ian Fleming, when put to the test, was never capable of actually pulling the trigger and killing another man. In many ways, it makes him much more human—he realized at that point that he did not have the mentality of his brother.

BROWN: Why do you think Bond is such a compelling character?

COOPER: It’s an ever-changing question now, because if you look at the Bond of old, people wouldn’t stand for it. I think even if you read those earlier books, his treatment towards women is terrible, his general attitude, his humor. He’s a very old-fashioned idea of someone, which doesn’t work so well in today’s society. But what he was early on and what he has become, is someone who represents a very exciting existence. He’s a hero. He’s an extraordinarily suave, sleek, cool hero. The idea of him is very compelling and removed.

BROWN: Did you find doing it in a miniseries format to be more rewarding because you had more time with the character, or just more grueling?

COOPER: It was grueling in terms of time. I’ve never known a schedule like it. All the more credit to the Director of Photography and the director, Ed Wild and Mat Whitecross. They were extraordinary in what they had to achieve, and I think it looks very filmic—they made it look beautiful. You’d be very surprised by the amount of time we did that in. But in retrospect, I actually really enjoy working like that, because you aren’t given too much time to analyze or regret decisions that you have made in the spur of the moment. Any artist, I’m sure, would say that, more often than not, their instincts towards a decision are the best. And that time constraint gives you no room or possibility to regret; you’re running on instincts, and they’re normally right. Once you’re immersed in that characterization, you react in a very natural way as the character you’ve created would. It gave me more time to explore the person, the man, the story, the time. Condensing a biopic in a short space of time for a film is very tough. That’s why often you have to make it about a very specific time in that person’s life—a day in a person’s life. But because the series is in four parts, we had the ability to [explore his life]. He had an extraordinary life, there’s so much to tell.

BROWN: Do you approach playing a real person differently to when you’re just playing a fictional character?

COOPER: Well, there’s a much bigger responsibility playing a real-life figure. My worry with this was that I immediately had no physical resemblance to the man. Once I’d spoken to the producers and the director about what we were trying to achieve, I felt much more comfortable in my ability to create a character rather than make an accurate detailed, biographical account of his life. I’m sure the people who knew Fleming well would say it’s not a fair representation of him, but it’s an idea of his imagination playing out. It’s an idea of the man who he was writing about rather than himself. But, saying that, [playing a real person] is wonderful because you’re constantly met with a wealth of information. You have very detailed biographies about the man and all that helps you put together a real-life person. And it’s often when you’re making up those details in your head that—making them up from scratch —that you have moments of regret or indecisiveness towards that detail being right. Like his relationship with his mother, who was by all accounts the majority of time very disappointed in him—that’s there. I know that to be true. It gives a very clear, immediate understanding of what affected his relationship with women, and that’s an amazing tool or gift for a character, as a basis of who a person is.

BROWN: Is it difficult not to get ahead of yourself when you know exactly what happens to him throughout his whole life?

COOPER: Is it difficult not to play the ending, you mean?

BROWN: Yes.

COOPER: Actually, I didn’t think much about that. I ended up feeling quite sorry for him and his loss: firstly, his loss of his first love, which his mother prohibited, and stopped him from following through with. And then his second love, who was killed by shrapnel in the War, and then his inability to really commit to the person he eventually married. And if I played the ending, I would know that they did eventually end up together, be it very unhappily. But I felt very moved by his inability to marry. So no, I don’t play the end. It’s the same with any character, except for how they develop TV shows now, where you’re very unaware of what the future holds. I like to know the arc of the piece, and I’m careful not to give it away and play the end.

FLEMING: THE MAN WHO WOULD BE BOND PREMIERES TONIGHT, JANUARY 29, ON BBC AMERICA.