literature

Dennis Cooper and Richard Hawkins on Books, Naked Bodies, and OnlyFans

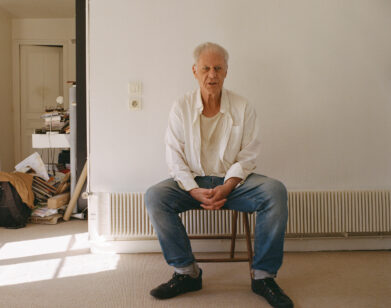

In the puritanism of American fiction (with its endless moral posturing, constant need for redemption narratives, and characters that seem required by law to learn valuable life lessons by the end of their run), Dennis Cooper stands like a pagan god—wild, fearsome, fulsome, something to worship and tremble in front of, and maybe even to feed a little blood. Or perhaps Cooper is more like the bookstore bogeyman waiting for you down at the end of the isles of flowery fiction, ready to swallow you whole. Or maybe he’s just a different kind of literary mystic. Whatever Cooper represents in the landscape of contemporary literature, he’s without a doubt one of the most vital and important writers to emerge in the past 50 years, and his genius goes far beyond mere taboo-breaking (although it’s very difficult to read one of his deadpan, hardcore novels and not walk away a few degrees less innocent than you were on page one). Cooper’s books are dissection tables of desire; they take a bone saw to the dreams, sexual fantasies, obsessions, youthful delusions, and myths of fame and individuality that have come to define our private and public selves.

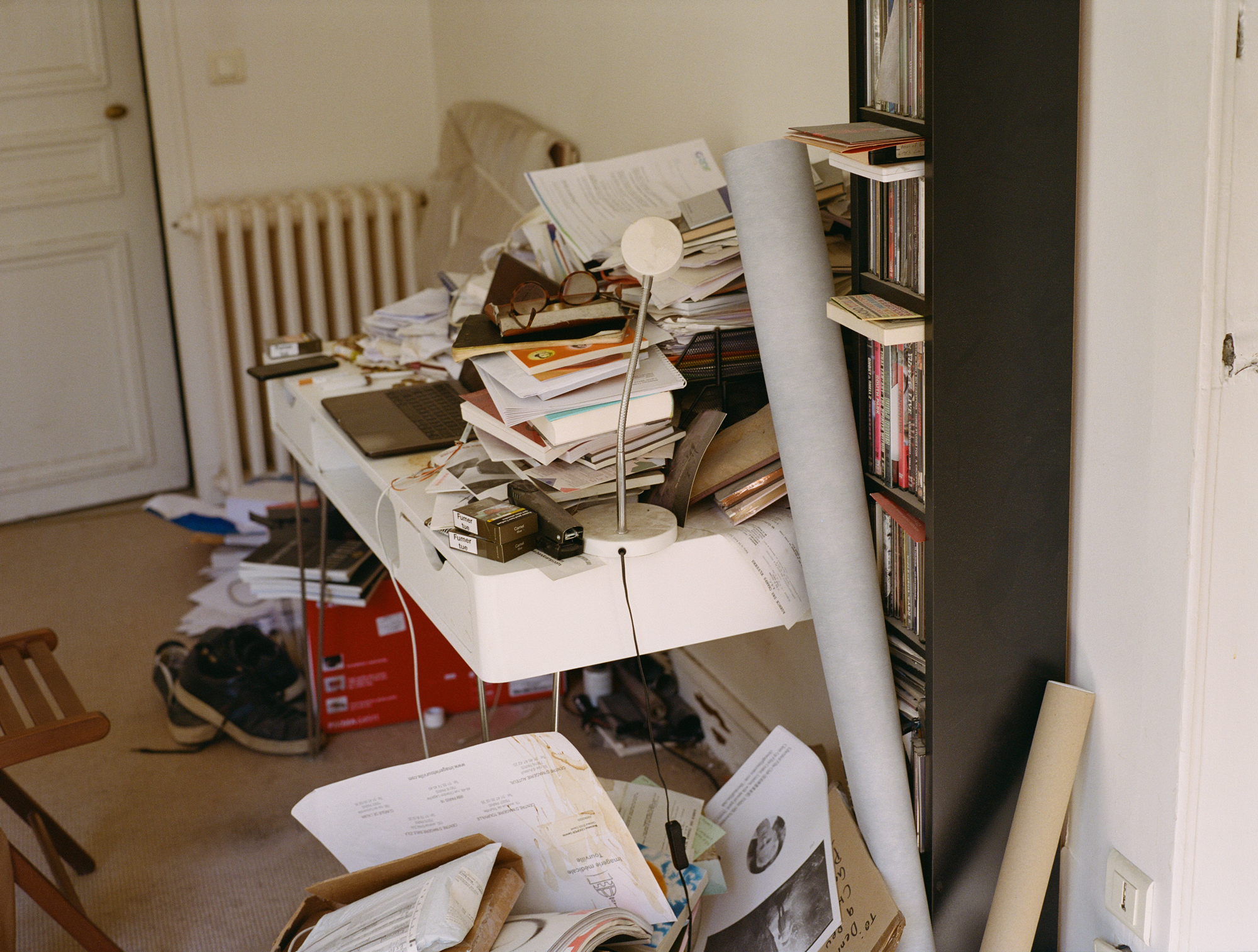

The 68-year-old writer, who was born in Southern California, and has lived for the past decade and a half in Paris, has written a number of transgressive marvels, such as The Sluts (published in 2004, composed primarily from emails, chats, and online message-board posts that rate and review gay escorts), My Loose Thread (2002), and The Marbled Swarm (2011). But he is probably best known for his five novels that makeup the George Miles cycle, a diverse yet loosely interwoven brood of books—Closer (1989), Frisk (1991), Try (1994), Guide (1997), and Period (2000)— that read like a requiem on young love and a psychological mapping of the death drive while plowing through the everyday incidents of sex, drugs, gay porn, dismemberment, teen heartthrobs, snuff films, technology, and hanging out at home jerking off in the downtime between trips to the inferno. These books are shocking and riveting and essential, and they make us anything but passive consumers in their plight. In fact, the cycle was planned long before the author started working on it in the mid-’80s; it was first conceived back when Cooper was a teenager and had fallen in love with a boy in school on whom the figure of George Miles is based.

This fall, Cooper releases his first novel in ten years, I Wished (Soho Press), which, like many of his works, includes characters named Dennis and George. While it would be hazardous to suggest that I Wished is somehow more “personal” than Cooper’s previous output (the writer has long toyed with the reader’s impulse to misconstrue fictional elements as highly stylized autobiography), it does touch on the “real” George Miles’s mental breakdown and ultimate suicide as an adult, gun to head, in the bathroom of his family’s house. And, ultimately, this moving account elicits a very different variety of “oh my god” than Cooper’s other short stories and novels. I Wished Is also a jigsaw of approaches and voices, and covers disparate zones of interest—Nick Drake, drug addiction, James Turrell, Santa Claus, art, LSD trips, and musings on the attempt to connect—all bundled together in what the author calls “the pornographic slaughterhouse that you call prose.” Cooper has never limited his artistry merely to novels. He’s also a poet; has worked in dance, theater, and visual art; kept up a daily blog that could double as an open-ended art piece; and has recently turned much of his attention to making films with his co-director Zac Farley. This past April, as Cooper was hanging out in his Paris Apartment during another national lockdown, he zoomed with his old friend in Los Angeles, the artist Richard Hawkins. The two met back in the late ’80s and co-curated groundbreaking art exhibition in L.A. in 1988 called Against Nature that tackled the prevailing fears, anxieties, and homophobia of the era. They hadn’t spoken in a while, so naturally they got right down to the heart of the matter. — CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

———

RICHARD HAWKINS: Shaved, trimmed, or natural?

DENNIS COOPER: Regarding What? Dudes? Gosh, I think they’re all great.

HAWKINS: I don’t mean their face.

COOPER: Trimmed is probably the least appealing, just because it’s so in your face. With shaved, sometimes I’m like, “I totally buy it,” except when they have really hairy legs or something. They have to shave everything for it to work.

HAWKINS: I just think there should be some kind of anti–pubic-hair–shaving action committee.

COOPER: You’re against shaving?

HAWKINS: Yeah. I’m only remote viewing, but, aesthetically, I’ll just click off if it’s trimmed.

COOPER: Yeah, sometimes they look as hairless as statues.

HAWKINS: Any Chaturbate or OnlyFans suggestions, or is that not your thing?

COOPER: I don’t do Chaturbate, for some reason, and I don’t subscribe to any OnlyFans. I just rely on the free sites. I’ll look at the model’s Twitter, which is usually enough. I’ll take that three seconds or 30 seconds from the OnlyFans. I have been tempted by Jerome James. Do you know who he is? He’s the big French twink bottom pornstar. He has this punky hair. He’s a skinny little thing. But he’s just insanely wild and he posts these orgies and gang bangs every fucking day. I see him on the Métro once in a while.

HAWKINS: I wonder if you would like @SunLightRemedy. I think he’s Australian.

COOPER: That’s a good name.

HAWKINS: He might not be your taste. But, yeah, he’s been doing lots of LSD recently and he tries to make these rap songs. But then in the next post, he’s jerking off. And he’s got a lazy eye. Anyway, congratulations on the film work. You’ve been collaborating with this young filmmaker, Zac Farley. Was Permanent Green Light [2018] the first one you worked on together?

COOPER: Zac went to CalArts and then left CalArts for Northwestern, but he made videos and art and stuff. He’d never made films until we did Like Cattle Towards Glow [2015], which was our first one. Zac and I are very symbiotic. We’re going to shoot the next one in L.A., actually. Stefan [Kalmár] at the ICA in London is going to produce it. They’re raising the money right now.

HAWKINS: Stefan is really great.

COOPER: I’ve known him for a longtime because of working on all this film stuff. Gisèle Vienne, my collaborator on theater stuff, told me that he was boyfriend with [the artist and dancer] Michael Clarke For many years. I had no idea. He never told me.

HAWKINS: Oh, yeah, a long, long time. Stefan saw the Bob Mizer & Tom of Finland exhibition that Bennett Simpson and I put together at MOCA and brought his own version of it to Artists Space in New York—or at least the Tom of Finland portion. He was the most cut-through-the-BS, get-it-done kind of guy. Speaking of Gisèle Vienne, I watched an interview you two did about the piece you showed for the Whitney Biennial. [In 2012, Cooper and Vienne exhibited a sound-sculptural installation of an animatronic adolescent boy talking with a puppet.] From what I could tell when I saw the piece and heard the text, standing in front of it, there was a kind of body-rejecting-the-self or the-self–rejecting–the–body thing, which is very [Antonin] Artaudian.

COOPER: It’s very Gisèleian, too.

HAWKINS: I guess it was the voice characterization, too, which reminded me of that last audio recording of Artaud’s, To Have Done With the Judgment of God [1947]. So let’s talk about your new novel I Wished. I thought it was an incredible example of the creative process and how a kernel of an interaction splinters into a machine filled with multiple narratives and drives. There are sections where it feels like the reader is involved in the construction of it, and yet it reads like a memoir.

COOPER: It’s not a memoir, but yeah.

HAWKINS: There’s the title verso page at the beginning that says, “This is a work of fiction.” But I did see some rabbit holes while reading it and I also went back and read your last novel, The Marbled Swarm. In that book, I was so distrustful of the narrator, but it sucked me in. I Wished sucks me in, too, but it also throws me back out. It makes me think it’s an admission of guilt as well as this work of mourning, if not devotion.

COOPER: Well, I Wished is super sincere. It’s not like The Marbled Swarm, with that super real, exploding emotion. I had to build a machine, like you said, where I could actually explode but there also had to be something to read that was engaging. I spent seven months writing a first version of it, which was very emotional and tough for me to do. It was just terrible. I looked at it afterwards and there was nothing there. I did salvage one part in I Wished—the part about The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, about the first night I met George. That is the only thing in the book that’s absolutely factual. Everything else is very fractured out.

HAWKINS: The parts with the Nick Drake music sent me down another Google hole.

COOPER: Yeah, he was apparently listening to Nick Drake when he killed himself. The reason I found out George killed himself is that a friend went to AA and some guy stood up and said, “I’m having a hard time because my friend George Miles killed himself ten years ago,” and that’s how I found out. So I talked to this guy and the last thing George ever said was, he called this guy really late at night and said, “I can’t stop thinking about Nick Drake. You have to call me. We have to talk about Nick Drake.” He was obsessed with Nick Drake.

HAWKINS: There was this article in The Guardian last year with the most deceptive headline—“Greek, without the sex”—about [the musician] John Martyn’s relationship with Nick Drake. Did you read that?

COOPER: I read a biography of him, and I think that story was in there. That’s how I got all that stuff about him going into this junkie’s place.

HAWKINS: Maybe this is a stretch, but you don’t think Mike Kelley was thinking Day Is Done?

COOPER: You mean when he died? I don’t think so. It still completely bewilders me that he did that. I never would have thought it. I still can’t accept it. It’s weird.

HAWKINS: This is going to date me as well as you, but when Mike Kelley did the Patrick Painter Gallery installation, making a mosaic sculpture from the stuff he’d dredged up from the Detroit River [for the 2002 show Black Out], I wrote Mike an email that was like, “This is the most personal thing I’ve ever seen from you and I think it’s such a great transition.” Mike finally wrote back and said, “I haven’t jumped on the sincerity bandwagon. I don’t see myself doing that anytime soon.” I was a bit disappointed in that. I don’t know about the rest of L.A. or even the art world, but I think about this probably at least once a week. It’s like the art world seemed more accepting and balanced or something with Mike in the world.

COOPER: I totally know what you mean. It’s weird, yeah, and I feel that way about [the New York gallerist] Hudson, too. It’s really hard for me to accept that he’s not around because he was just this total White House of a person for me.

HAWKINS: Absolutely. I think I was in the midst of searching the Tony Greene archive and I had tried to contact Hudson several times and, a week before he died, he called me back and, because records from Feature [Gallery] were inside his head, he gave me all these leads within a 15-minute conversation. I feel really lucky to have had some late contact with him because you’re right, he was just the best, most open-minded supporter. I think, through you, is how I had my first introduction to the art world, by having a show at Feature. So, yeah, these are magnificent losses. Okay, now I made some more notes in I Wished. I noticed these attempts to unify the love object in this novel. Especially with this narrator, it’s almost like his suffering, his wanting to be loved, is what unifies the love object. I know you didn’t grow up with religion—

COOPER: No, I didn’t.

HAWKINS: But to me, there’s something Christ-like going on there.

COPPER: Well, I always thought that all that Christian stuff was really useful to work with, even if I don’t understand it. I have a really, really super sublayman’s understanding of all that stuff because I never grew up with it.

HAWKINS: I’ve been looking at a lot of Renaissance painting lately, so I’ve had to reinvestigate the ins and outs of the Catholic church. As I was researching all of this stuff, I came across this 18th-century thing called Quietism. Have you ever heard of this?

COOPER: Vaguely.

HAWKINS: Quietism was eventually judged heretical, but it is heretical because one now has a relationship to Christ without an intermediary, like the church. It’s like immersive meditation on the suffering as well as the salvation of Christ, so that one goes through ecstatic and devastating periods as one is 24/7 in prayer with Christ. And that seemed like such a parallel, again. But that resonates to some extent. I think it was St. Gregory who Christ appears to, but in the size of a crucifix—basically the size of a sex toy—and there are paintings of St. Gregory with his mouth open and this little Jesus squirting blood out on him.

COOPER: Wow, I’ll look into that.

HAWKINS: It interfaces with the altruistic characterizations that you give the narrator.

COOPER: Right, right. I don’t know where that comes from. I don’t have any model, like you said. It’s like a recipe or something. A lot of it is figuring out the right recipe for where the ingredients go. For me, when I write, it’s always like that. It’s like I have to make this thing work and so I’m trying to finesse everything so that everything works well. I get really technical when I write.

HAWKINS: Technical in what way?

COOPER: When I’m concentrating, the stuff just pours out and then I’m trying to control it. I’m trying to make it work. It’s like mixing a song or something.

HAWKINS: Making it work linguistically, you mean?

COOPER: Yeah, making it really dynamic, then thinking about the rhythm and how the rhythms are working. A lot of this stuff comes in and I don’t even know why I do it.

HAWKINS: There’s an abstraction process probably, where you’re moving the content around to resonate.

COOPER: That’s what I’m consciously thinking about it, yeah.

HAWKINS: This is also the first time I’ve read a clinical diagnosis of the love object in your work. Here he is characterized several times as bipolar.

COOPER: Well, he was. Yeah. Or the earlier term for it, manic depressive. Then, when he got older in the early ’80s, he had been diagnosed as psychotic.

HAWKINS: I’m curious why the narrator is never diagnosed in the same terms. I don’t mean Dennis Cooper who is sitting in his apartment in Paris. I’m talking about the narrator.

COOPER: I don’t know. As for me, I went to therapy for three years in the early ’90s and it was really soft-core. It was this woman who was the psychiatrist of Sylvester Stallone and she was just super nice and there wasn’t much to it. I’ve never taken antidepressants. I just try not to think about it. I don’t like to think about myself. I just like to keep moving forward.

HAWKINS: Speaking candidly, I have some of those borderline traits. Not full borderline traits. But traits, like treats, that certainly affect my love relationships. And it seems like the thing that you and I have in common, at least the artist that I project within my own practice and from narratives that you work with, is that there is a kind of old-school, unrequited love thing going on there. I think there’s even a line in the book about a preference for the unavailable love object. Here it is: “When everyone you know is either very far away from you or hides, you find someone dead to love.” And that kind of distanciation, that way of being involved with them, has always been my erotic hinge or something. Anyway, there does seem to be an anti-psychiatry bias in the book.

COOPER: I’m more of a Blanchotian guy. [The philosopher Maurice] Blanchot was all about how the self is meaningless, the self is nothing, all that kind of stuff. There’s that part in the novel where I say that I went to therapy and I just wanted to tell the therapist about George and George’s problems, and she kept saying it was about me. And I used to say to her, “Forget about me. I’m telling you about him. Just think about him and don’t even think about me.” It was really weird and she was like, “Whoa, that’s not my job.”

HAWKINS: In the novel, George is transformed into so many dimensions, some of which get deified, while the others get crucified or layed or dissected. By the way, did you ever manage to track down the grandchildren of [the late French porn star] Pierre Buisson? Are they hanging out on every street corner?

COOPER: I don’t think he had grandchildren. He was, I think, gay, and he died a long time ago. One of the things that I wanted to do when I got to Paris was actually go and interview [the porn director Jean-Daniel] Cadinot about Buisson, but I never got around to it and then Cadinot died. But I do know that [Buisson] died of a heroin overdose not too long after he made his last film with Cadinot In 1984.

HAWKINS: Well, I saw the spirit of Antinous incarnate in the Castel Sant’Angelo in Rome about ten years ago. So I’m sure if you look around you can still find these things. Did you watch Des, the film about [the gay Scottish serial killer] Dennis Nilsen?

COOPER: I have not.

HAWKINS: It’s interesting. It’s also disappointing how Hollywood treats a killer. I think you were the one who lent me Killing for Company [a 1985 book about Nilsen by Brian Masters]. I feel like the film doesn’t give Nilsen the dimensionality of his character. He’s just resistant and overly grand.

COOPER: Nilsen’s autobiography [History of a Drowning Boy, which he wrote in prison] is out now, too, right? Someone I know read it and said it was extremely disappointing.

HAWKINS: And it’s edited down from 6,000 pages. Do you keep up with other serial killers? Like Sasquatch?

COOPER: Like Bigfoot? Or the Abominable Snowman? I did a post about him on my blog not too long ago. All the sightings, all the millions of pictures people have taken of him.

HAWKINS: Have you ever heard the vocalizations? The vocal recordings are so strange and haunting. Isn’t there a section in one of your books where a character is described as a dog trying to pronounce the word “mama”?

COOPER: It’s “I love you,” but I can’t remember which book that is. It might be Try. I knew a woman who had a friend who had a dog that used to say “I love you,” and it always really disturbed me.

HAWKINS: Getting back to I Wished, I loved the James Turrell interlude, which is like a roller-coaster in the middle of the novel.

COOPER: More of a dark ride, but yeah.

HAWKINS: A runaway mining train. Kanye West did a film in Turrell’s Roden Crater.

COOPER: I was so disappointed when I saw that, because the novel was finished and I was like, “Oh, no. Kanye West did something about Roden Crater, that’s mine. He’s going to fuck up my fucking reference point.” But I don’t think it really made such a big difference.

HAWKINS: I couldn’t find anything on the internet about the title of the section, “THIALH.”

COOPER: It’s an acronym for The Heart is a Lonely Hunter.

HAWKINS: I did find a few interesting anagrams for George Miles Name. Slim gore gee. I emerge slog. Ogle rims gee.

COOPER: You remember that my name is “sinned” backwards, which is the only good thing about my name.

HAWKINS: Yeah. All I have is Drahcir Snikwah, for those of us who do those kinds of things. So, tell me, what is this new film you’re working on with Zac that’s set in L.A.?

COOPER: It’s about a really weird family that turns their house into a haunted house attraction. We’re Going to shoot it in Southern California, hopefully early next year, depending on if I can travel.

HAWKINS: Are you finding that film-world people are superficial and suspiciously nice?

COOPER: I find them to be enormously flaky. I’ve never seen such flakiness. That’s what I mostly find. The first two films were done through film producers, but I’m really happy because this one is through the ICA. I’m much more comfortable going through an art context. They don’t have any bullshit about having to earn the money back or any of that stuff. They’ll show it at PS1 and whatever. That’s much more my speed. And when we’ve shown the films in an art context, the screenings are always the best.

HAWKINS: You definitely end up getting more interesting questions.

COOPER: Yeah, and if you show it to a film audience, they’re like,“This reminds me of Elephant.” And it has nothing to do with fucking Elephant.

HAWKINS: What about The Elephant Man?

COOPER: Yeah, maybe. It had more to do with The Elephant Man than Elephant for sure.

———