David Gilbert’s Family Legacy

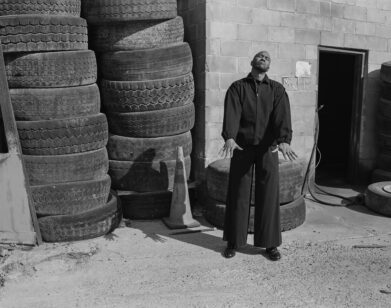

ABOVE: DAVID GILBERT AT HIS HOME IN NEW YORK, JULY 2013. PHOTO BY CHRISTOPHER GABELLO.

& Sons begins with a funeral. Charlie Topping, an unremarkable member of old-money New York, has died, leaving behind two grown sons, a daughter, a second wife nicknamed “Mrs. Oyster Bay,” and his best friend, the reticent, J.D. Salinger-esque writer A.N. Dyer. Always second fiddle to his famous friend, Charlie’s funeral is quietly overtaken by devotees of Dyer—brilliantly described as death’s “unfortunate bride’s side.”

The second novel by New York-born writer David Gilbert, & Sons is an expansive and enthralling family mystery. We learn about the Dyer family through the eyes of Charlie’s youngest son, Philip, a man in the midst of a crisis. Philip seems omniscient, but his personal flaws, sense of rejection by A.N. and his sons, and occasional references to “narrative fraud” remind the reader not to blindly accept his account. With it’s abundance of sympathetic, fully-formed characters, & Sons is a book that begs a second—and possibly a third—reading.

Gilbert, whose other work includes a collection of short stories, recently sat down with his friend Janet Borden. Gilbert is an avid collector of photography and Janet his go-to gallerist.

JANET BORDEN: We know each other because we collect photographs.

GILBERT: I love photographs. You were the first gallery I think I went to.

BORDEN: No, you tried to go to Sonnabend Gallery. They weren’t nice to you. They were mean to you.

GILBERT: They didn’t open the back door, and they didn’t have cupcakes and treats.

BORDEN: We were looking for [a] David Levinthal [print], and then you said, “What else should I be looking at?” I said, “[Lee] Friedlander!” and as you went through his book, you said “Oh, that’s my mother!” [to one of the portraits].

GILBERT: That was the weirdest thing. I recognized it because of the tennis bracelet she had on that I remembered from my youth—that she probably hadn’t worn in 20 years. I was like “Oh, I remember that bracelet…” and then, “That’s my mother!” I remember getting really concerned as we were flipping towards the back, and then suddenly we hit the nudes and I was like, “Oh no. I hope I’m not going to see Mom ’70s bush style.” [both laugh]

BORDEN: I don’t remember that book being that naked the way you remember.

GILBERT: Well, when you’re a photographer that’s kind of the whole spiel! That’s why you get into it—take off your clothes.

BORDEN: [laughs] There’s a very literary strain in your photography collecting and a very photographic quality in your writing—just the way you write about describing things.

GILBERT: I think that’s very true—to stop that moment and really try to explore it.

BORDEN: The wonderful banality of…

GILBERT: Are you calling my writing banal?

BORDEN: [laughs] No, no! I think you’re very good. My only other observation is that people don’t eat much in your writing.

GILBERT: I’m a good WASP. I find food to be very stressful. I think it might come from my mother a little bit, because food and clothes shopping—those two things put panic in my heart.

BORDEN: But you have a very nice shirt on today.

GILBERT: Thank you, my mom picked it out. [both laugh] But that’s how I shop. It’s not, “What would Jesus do?” it’s “What would Mom do?” But yeah, there’s no food. Then you’ll find a scene in the book where they find a pretzel. They go searching for a pretzel. There’s not a lot of food in my writing, that’s for sure. But in my [photography] collection I have that Eggleston roast beef, which is one of my favorites. With a coke and rum. It’s probably RC cola, too. It’s not a coke. My book is a lot about time and the past, and I still wake up once a month wishing I had bought more Egglestons back in the day. How do you feel about how expensive photography has gotten?

BORDEN: I just feel like a hoarder.

GILBERT: Oh, really? I guess it’s a matter of really enjoying those early days.

BORDEN: Your collection is so amazing because it is personal.

GILBERT: It’s very personal.

BORDEN: But there’s a narrative strain in it that’s very indicative. You’re a landscape upon landscape collector.

GILBERT: I would describe it as just incredibly narrative based. Still, my favorite thing that I’ve gotten in the last 10 years is that tiny little Cindy Sherman where she’s dressed as a fairy, and it says “Merry Christmas” in glitter. That’s me, and it’s tiny and it’s certainly not archival and it has a little cutout doily. [laughs]

BORDEN: It’s like a little secret. Do you think your writing is like photography? The way you write, there’s some visual correlation. It’s descriptive. I’m not sure how you explain it.

GILBERT: It’s not terribly profound, but it’s certainly got that truth versus fiction that photography does. I certainly like to explore that, especially in this new book—how one bases one’s memories on those snapshots. The memory is long gone, but you could swear you had it right there. The picture of you and your dad on the beach—you’re like, “Oh, I remember that.” You don’t remember anything—you just remember the photograph, even though the photograph could be 30 years gone. You remember growing up seeing it on your mantle or in your little scrapbook. So that’s the memory.

BORDEN: It’s very hard to explain photographs. It’s very hard to explain that thrill if you’re a collector of photographs. I don’t think it’s just acquisitive in your case.

GILBERT: I wouldn’t call myself at all an intellectual collector who’s collecting a history of photography. It just comes down to the image. It’s intellectual because you enjoy it and it reflects who you are. What I like about is that it seems very democratic. Anyone can pick up a camera and do it, yet these people have done it in such a way that it’s taken into a mysterious place. It’s [like] writing in that way, too. Anyone can write, really. We all have the tools to write, it’s just putting words in a certain order that suddenly opens up a whole world that you couldn’t have imagined before and a photographer does the same thing. Painting, film, sculpture—it doesn’t quite hit me the same way. I don’t know why. Film is close, but it’s so narrative.

BORDEN: Is your family really worried that they’re in your book?

GILBERT: My dad really liked the book—he loved the book. My mom liked the book. She always said there were too many movies [around] and they’re all too long. But she’s all about brevity. In an hour and 20 minute movie, she’s like, “Oh boy, that really dragged!” My sister enjoyed the book. My brother is reading it, or not…

BORDEN: [laughs] And your children, have they read it yet?

GILBERT: They’re desperate to read it. Well, they’re really curious about all the bad words. My kids are like, “How many bad words are in it?” I’m like, “A lot.”

BORDEN: A lot of fucking bad words.

GILBERT: They’re in that age where bad words are still magic. They’re the best words ever.

BORDEN: The book’s set where you grew up, though, right?

GILBERT: Yes, I grew up on the Upper East Side and I never thought I wanted to write about the Upper East Side because I was always embarrassed about growing up there and going to private school—it just seems so pretentious and ridiculous. I used to lie, like when I went to summer camp I’d say, “Yes, I go to a public school in Southampton.” It finally took me until my mid-40s to be like, “You know I can write about the Upper East Side.”

BORDEN: It’s very funny. It’s like you write more as a time than a place.

GILBERT: This story theoretically takes place in the future. But that’s the thing about the Upper East Side, when you think about all of Manhattan in the last 15 years—it’s head is spinning how it’s changed. In the ’70s you wouldn’t even say “Alphabet City”—it was so scary. SoHo was just a different place. The Meatpacking district was actually a district for the packaging of meat as opposed to the packaging of New Jersey. Between 96th Street to 59th Street, nothing much has changed. Everything else is in such flux.

BORDEN: Do you think that’s insulation by money?

GILBERT: I think it’s that old money thing: old money is the hardest money to change and everyone wants to—in some way or form—participate in it.

BORDEN: So Ralph Lauren has a place.

GILBERT: Yeah. You kind of go there to be absorbed by it. In other neighborhoods in New York, [there’s a mentality of,] “I’m going to go now and move to the West Village and be bohemian,” even though you just bought your $12 million townhouse and work at Goldman Sachs. But the Upper East Side, it’s like you are not only living in a place, but you’re living a certain mode of personality and participating in it.

BORDEN: Well, you fought very hard not to live up there.

GILBERT: Yes. I moved to the most Upper East Side building downtown.

BORDEN: Well, baby steps.

GILBERT: Manhattan is now, as I said, all the Upper East Side. It’s all blown out by money.

BORDEN: Yes, but your neighborhood also hasn’t changed that much because the residential stuff is a landmark.

GILBERT: I find that the West Village has changed dramatically. Mainly because of all those great old walk-ups that used to be broken into five or six small apartments that were all rent-stabilized. There really have been some interesting people have lived there.

BORDEN: It’s where writers lived.

GILBERT: Where writers lived, where actual artists lived. Now it’s just all been taken back to single-family houses that I walked by with such jealousy in my heart. I want to live there. They’re so beautiful!

BORDEN: Really?

GILBERT: Oh, sure. They’re nice, those townhouses.

BORDEN: Well after the book, you can sell it for a movie adaptation. Has anyone else asked yet?

GILBERT: Not yet.

BORDEN: Well, it just launches today.

GILBERT: Let me check my email really quickly…

JANET BORDEN RUNS JANET BORDEN, INC., A GALLERY IN SOHO, NEW YORK.

& SONS IS CURRENTLY AVAILABLE VIA AMAZON, BARNES & NOBLES, AND INDEPENDENT BOOKSTORES. FOR MORE ON DAVID GILBERT, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.