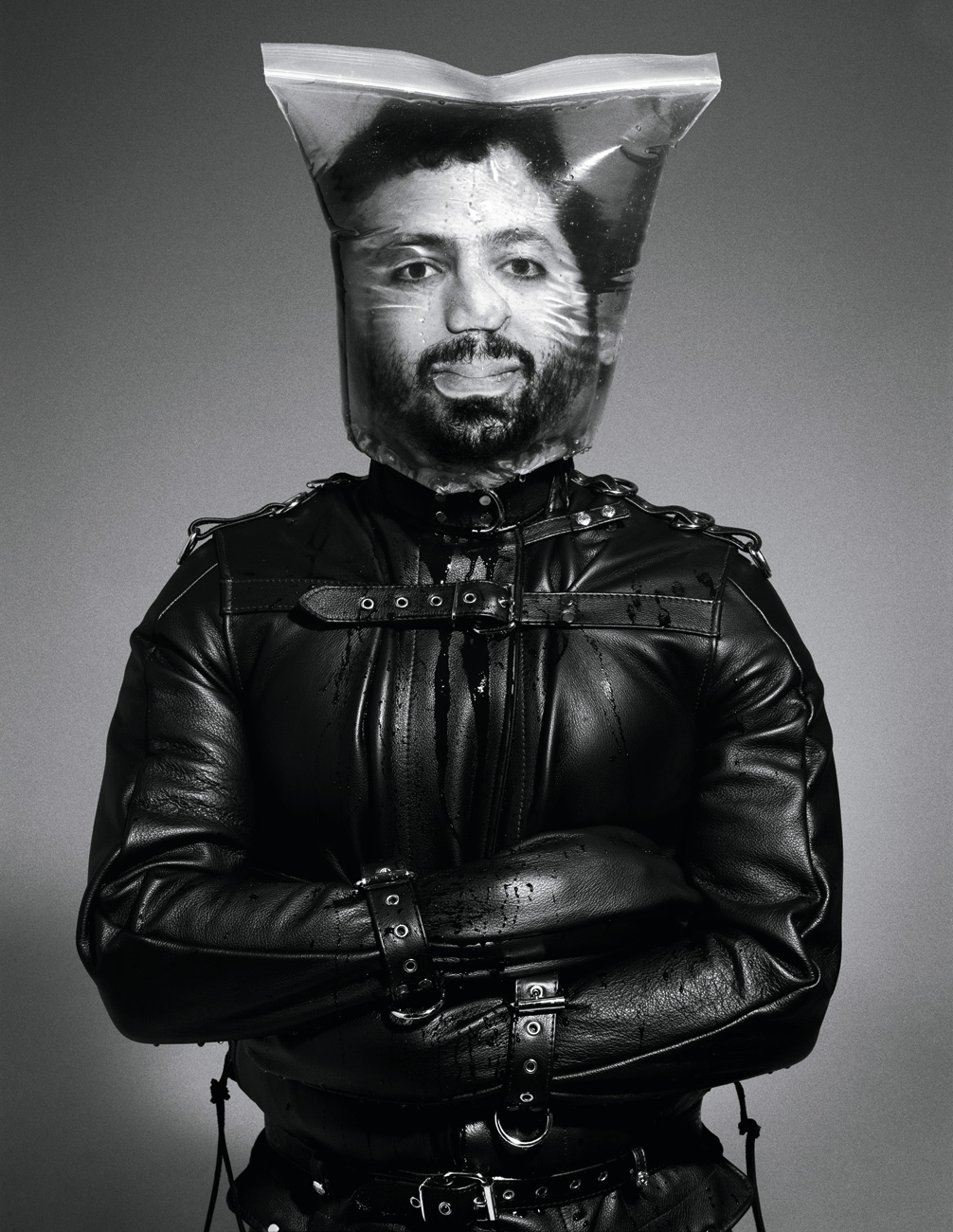

David Blaine

Coat and shirt: Brioni. Jeans: Levi’s. Shoes: Church.

In September 2009, magician David Blaine chartered a sailboat with menswear designer Adam Kimmel and marine photographer and filmmaker Bob Talbot to perform yet another feat of endurance, bravery, and, some might argue, complete insanity. The reason for the expedition was simple enough: Blaine was planning to swim in open water with roughly 20 great white sharks. He lowered himself into the water with no body armor—save for an Adam Kimmel spring/summer 2011 tuxedo. As he descended beneath the surface, the sharks began to circle him. At one point he touched a passing fin; at another, he seemed to be smoking a cigar underwater while a great white inched behind him.

Talbot captured Blaine’s stunt in a short film tentatively titled Dressed for Dinner. For most people, the footage looks either like the document of a man with a death wish or a piece of Hollywood CGI trickery. But in the last decade, the 37-year-old Blaine has gone to great lengths to prove time and again that he isn’t like most people—or perhaps most accurately, he has spectacularly demonstrated the very limits and extremes that a human body is capable of surviving.

Born and raised in Brooklyn, Blaine started out as something of a New York street performer—an expert at card tricks and sleight-of-hand illusions. But he quickly gained notoriety with a series of very public, very harrowing endurance feats that tested his ability to withstand extreme forces as much as they did the nerves of the audience watching him. In 1999, Blaine lay for seven days in a claustrophobically restrictive clear coffin across from Trump Place for his stunt “Buried Alive.” The spectacle transformed him from a cool young wizard running with a fast downtown crowd into a mesmeric body artist who was challenging our understanding of stamina, control, and survival. Other tests quickly followed, each one a stunning, dramatic death-defying performance that continued to separate Blaine from the David Copperfields of the magic world: In 2000’s “Frozen in Time,” he was encased in massive blocks of ice for 63 hours. In 2002, for “Vertigo,” he stood on a 100-foot pillar in New York’s Bryant Park for 36 hours without a safety net. In 2003, he sealed himself in a Plexiglas box suspended over the South Bank of the River Thames for 44 days and nights for “Above the Below.” In 2006, he was submerged for seven and a half days underwater in a glass orb at Lincoln Center, and then tried—and failed—to break a world record for breath-holding. (He subsequently did break another breath-holding record in 2008 on The Oprah Winfrey Show, going without air for 17 minutes and four seconds.) A couple of years ago, in “Dive of Death,” Blaine hung upside down in Central Park for 60 hours.

With these various feats, Blaine has revolutionized the contemporary world of magic, redefining the magician’s work as something more internal than supernatural—as about battles of will as well as tricks of the eye. The shark swim is just Blaine’s latest project as he prepares to cross the ocean next summer in a glass bottle. Blaine’s friend and sartorial accomplice Adam Kimmel recently spoke to him about his work, including the shark swim, and why his biggest dream challenge is one day beating the world record for staying awake.

I made a rule with everyone on the trip. The rule was that no matter what the shark does, we couldn’t hurt it. So if it did decide to grab me or take me under the ocean, we weren’t allowed to hurt the animal, because we were going into his territory. David Blaine

ADAM KIMMEL: I want to start off talking about our shark trip because I think that was the scariest and most life-threatening experience.

DAVID BLAINE: No, it wasn’t. [laughs]

KIMMEL: It was for me, and I wasn’t even in the water. It was enough just being on the boat watching these sharks circle around all day long, while you were 35 feet below the surface with no tank and no mask. I was really scared. [laughs] These are great white sharks, and we’re in the middle of nowhere! How did you first get the idea to swim with sharks?

BLAINE: I went on a trip with a bunch of scientists to that same spot by Guadalupe Island in the middle of the Pacific in 2007. We were in cages. But at the very end of that dive, I quickly jumped out of the cage. Bob Talbot was with me, so he got one minute of film of me outside of the cage with the great whites. Everyone on that trip got freaked out that I did that, and that was the end of the trip. But it was my dream to go back and do it again. The reason is because I think great whites are the most beautiful and perfect creatures I’ve ever seen.

KIMMEL: But in your mind, weren’t you wondering if it was safe?

BLAINE: I think it depends on your position. If you’re in the water and your head is up and you’re alert and controlled and not afraid, I don’t think they want to bother you. That’s the reason they’re such perfect creatures and have survived and haven’t really changed in 50 million years. They haven’t evolved, because they’re perfect for their environment. I think they minimize their workload, so if they have to do any work to attack someone, they’ll probably go for easier prey.

KIMMEL: I guess that’s why they didn’t eat you when you were floating in open water. At one point you were down there wearing a red cape. How did you know for sure that these sharks wouldn’t attack?

BLAINE: It’s in the way that we did it. We didn’t just jump into the water. It was a slow process. I started on the edge of the cage and floated backward and started holding my breath for as long as I could while floating backward. It was a little tricky because I didn’t have a mask on. I would see these big blobs going behind me and under me. It’s tricky when you aren’t wearing a mask because you can’t judge distance. So it’s a lot of relying on faith. But as they say about sharks, it’s not the ones you see that you have to worry about, it’s the ones you don’t see.

KIMMEL: You told me it’s the sharks that come from underneath that you really have to worry about. Swimming above them, which you did, is the most compromising situation.

BLAINE: I think usually they come up out of nowhere and just hit you from below. That’s the way that they normally do it.

KIMMEL: Right. But the point I’m trying to make is that you’re a lunatic and you have a death wish, but I know you’re never going to admit it. [laughs]

BLAINE: That’s not true. I think we played it pretty safe. I don’t think we pushed it as far as I would have liked to.

KIMMEL: I know that’s true because not a day goes by that you don’t talk about swimming around the island on the back of one of them.

BLAINE: It’s hard to explain how it feels to see this perfect, powerful creature swim right by you, with its eyeball gliding right past your face. I imagine it’s like looking at a bolt of lightning strike right next to where you are standing. For me, it’s like seeing something magical. It’s like you’re not aware of anything else but it. You’re not concerned or upset. All of your attention is focused on one thing.

KIMMEL: In the New York Post a few weeks back, there was a picture of a great white attacking a barred cage in the exact same spot where you swam. When you saw that, did you think, “That could have been me”? Or did you think, “Those guys must have been taunting the shark”?

BLAINE: Neither. They’re wild animals and can do anything. But I made a rule with everyone on the trip. The rule was that no matter what the shark does, we couldn’t hurt it. So if it did decide to grab me or take me under the ocean, we weren’t allowed to hurt the animal, because we were going into his territory. We went ahead hoping for the best and expecting the worst. Every time out, I didn’t get cockier. Every time I went out was like the first time. But it was also probably the most fun I’ve ever had doing anything. I was trying to take long breath holds. What I was doing was trying to keep my buoyancy neutral and not go popping up to the surface, where you’re easy bait.

KIMMEL: How long were you holding your breath down there?

BLAINE: A couple minutes each time, probably. It’s hard to say, because the water is so cold and I was being circled by about 20 great whites, three or four at a time. They seemed very curious.

KIMMEL: That’s an insane number of sharks. Was it really difficult to stay calm down there while holding your breath, unable to see anything around you?

BLAINE: Ironically, the most difficult things for me to do down there were to eat a banana and smoke a cigar. I asked Harmony [Korine], “What could I do with the great white sharks?” He called me back the next day and said, “Why don’t you smoke a cigar?” So then I called Bob Talbot, who’s shooting it: “Talbot, how could I smoke a cigar under water?” He said, “That’s easy. Just get a fake cigar and put some milk in your mouth. I bet you it’ll look just like smoke.” So the hard part was floating in the water and having to wait for a great white to pull up behind your head, cameras rolling. Actually, here is how it went: I’m breathing on a regulator. As soon as a shark approaches, I take out the Poland Springs water bottle that’s filled with milk. Then I hold my breath and suck the milk into my mouth carefully so none escapes. I put your sunglasses on. The great white passes. Talbot gives me a cue, and I start faking the cigar and then blowing smoke out, trying to look like I’m actually inhaling. As simple as it seems, it was a pretty complicated procedure.

KIMMEL: Well, it looks great. We’re just finishing up the final edits on the short film.

BLAINE: What’s cool is that we got to do it as an art piece, you know? We had nobody telling us what to do. There were no rules. We got to go into the open water with the great whites and just play and have fun and, and make cool footage. And most people that see it don’t even believe that it’s real.

One of the reasons I love doing these stunts is because as soon as you take away all the extravagances and superfluities that we live with every day of our lives . . . the simplest things become the most amazing. . . . You get this heightened sense of awareness. . . . It’s like an adrenaline rush.David Blaine

KIMMEL: You were born and raised in New York. How did you get started in magic in the first place?

BLAINE: Basically I was a kid growing up with a single mother in Brooklyn. I remember my mother had this deck of cards that her mother had given her and that she passed on to me. It was a gypsy tarot deck that I used to carry everywhere. I was about 5 years old, and we didn’t have too much, so the cards were one of my favorite possessions. I’d take the subway to school and have them in my hand. After school I’d go to the library by Prospect Park and wait for my mother to get done with work to pick me up. I remember one day this librarian pulled out a little book of mathematical card tricks, and she showed me how to do one. I did it for my mother, and she freaked out because she was so excited by it. She would make me perform it for her friends, and they all loved it. Around that same time, I’d go to Coney Island to hang out, and I saw a magician doing a rope trick on the boardwalk. I was fascinated. I guess that’s how it started. And then I remember finding a Houdini book at the library and seeing an image of him chained on the side of a building. He looked so intense and scary, and I couldn’t get that image out of my head. That started building up my love of magic. Then I began holding my breath as long as I could as a kid, trying to challenge everybody to see how long I could do it.

KIMMEL: Do you see any difference between the card tricks I’ve seen you do and the more extreme tests of endurance that you’ve come to be known for?

BLAINE: You know, whether you’re shuffling a deck of cards or holding your breath, magic is pretty simple: It comes down to training, practice, and experimentation, followed up by ridiculous pursuit and relentless perseverance. It has a lot to do with repetition. Holding your breath is another skill that you work on over and over, so it is similar. It’s all about trying to defy what people think is expected and normal.

KIMMEL: I think of you as an artist as well as a magician. And in your time, you’ve turned down a lot of commercial projects and stuck to your guns, trying to make your own projects without falling prey to easy money or quick entertainment.

BLAINE: The way I’ve always looked at it is like this: I think anything that comes too easy, I consider it devil’s money. So I figure if I don’t work hard to earn the money, then why should I take it? I take that into consideration for each thing I do, and that keeps me motivated to push the edge and give everything my all when I go forward on something. So, for example, if a company comes out and offers me a ton of money to do something I’ve already done, I don’t accept it. Because anything that comes easy isn’t worth doing. That’s been my theory since the beginning.

KIMMEL: I’ve heard rumors that you’ve been offered big contracts to do shows in Vegas.

BLAINE: Yes, I’ve been offered a lot of money to do that.

KIMMEL: How much money are we talking about?

BLAINE: I don’t want to say exactly, but I can say that some big magicians usually end up signing $100 million deals to spend a couple years in Vegas. There have been offers in to me to do that for a long time.

KIMMEL: Why did you turn it down?

BLAINE: When I do something, I want it to be great, and it just didn’t feel right for me, I guess. When I do a show, I want it to be something that’s everything it could be. I think there’s a sacrifice. You’ve got to work from the bottom up to build a good show. For my work, taking a $100 million deal and building some crazy Vegas spectacle isn’t really the secret to good art. That’s the thing. I believe the way to do it right is to work up the pieces from the inside out and to develop them slowly. You test them, you get them good, and then you can bring them all together somehow.

KIMMEL: What’s fascinating is how you’ve largely resisted commercialization, but you’ve still become a national icon. I mean, both Michael Jackson and President George W. Bush famously alluded to you in speeches. Is it hard to do what you want and not go the commercial route? How do you find the money to put these performances together?

BLAINE: Basically, every year and a half I do a big thing with ABC. It’s part magic show and part endurance tests that I create for myself. When I do these challenges, I try to imagine how they will look as an image, almost even how they will photograph. For example, how the water tank came about is that I started thinking about how someone would look living in a sphere. That’s mainly how I operate. Then I have to work doing magic—at private events and stuff like that—to pay for these endurance stunts. I try to do it my way. So basically, I work all year doing magic to be able to pay for these things that I dream up.

KIMMEL: So many of your public performances involve withstanding a condition for a long period of time. I think every single person who sees you must wonder what is going on in your mind. What are you thinking about while you’re standing on the top of a 100-foot pillar for 36 hours or you’re buried alive for seven days?

BLAINE: One of the reasons I love doing these stunts is because as soon as you take away all the extravagances and superfluities that we live with every day of our lives—the things that we adhere to as being so important, like cell phones and the need to eat your favorite food or worry about a billion different things—the simplest things become the most amazing. It’s very hard to explain. By clearing all of that extraneous stuff away, you get this heightened sense of awareness. Things like colors become more vivid and intense. It’s like an adrenaline rush—like a guy who rides big waves or jumps out of airplanes or a fighter. They are in that moment. So inherently that must be what I’m looking for.

KIMMEL: During your performances, have there ever been any close calls, where you thought to yourself, Oh, man, I’m not going to make it?

BLAINE: That always happens on every single one. Something always goes terribly wrong. Each one has its own craziness. It’s the little things you don’t think of and can’t plan for. For example, I went for the Guinness record for holding my breath on Oprah in 2008. My heart rate normally starts at 40 and drops down drastically to 8 to 10 beats a minute. But because everything was awkward and not prepared and it was done live on Oprah, it was really tricky for me to get into the same zone as when I’m rehearsing in pools—even though I had people throwing things at me and trying to distract me when I was training. It was still very different. My heart rate just escalated immediately and began at 120 and was up to 150. I started having ischemia to the heart, so it would jump from 150 to 20 to 140, skipping beats. I was going for the world record, which was 16 minutes, 32 seconds. At eight minutes, I knew I wasn’t going to make it. I was like, Oh, no, I can’t just quit now, because it’ll be a whole depressive show. So I overrode that and figured, I’ll just push, push, push until I black out. Then they can at least pull me out, wake me up, and hopefully everything’s all right. But at least for television it will be a big disaster. So I kept pushing, riding through the pain. My heart was jumping beats, but I kept pushing. I remember getting to the 15-minute mark, and I was certain that I was going to go into cardiac arrest. They had paramedics on standby with the equipment to jump your heart. The pain was overwhelming, but I just kept going. I surrendered to the situation and rode it out with the energy of the audience and finally made it to 17:04—the world record!

KIMMEL: But sometimes with your stunts, it isn’t even your own body you’re struggling with. You can be at the mercy of the public that’s all around you.

BLAINE: Yes, for that piece in London [“Above the Below” in 2003], I had outside sources affecting what was going on. I had a guy who thought my water was fake, like it was loaded with minerals and vitamins. To be honest, I also thought the people involved were spiking my water. So I would pour it down to Harmony, who was there the whole time, and be like, “Harmony, drink this right now. Is there something sweet in it?” I knew, though, that when you’re starving, you get something equivalent to a pear taste in your mouth. It’s natural when you’re starving to taste something sweet because you’re breaking the glycogens down out of your muscles and body fat. But this guy didn’t believe it. One night he ran up to the tower and ripped the water out. He drank it and of course it was real. Then he tried to shake the whole glass box, which would have been a really bad fall of 40 feet. So those outside circumstances can be really horrific as well.

KIMMEL: How important is setting a Guinness world record for you? Is that just a useful target or is there something about achieving an official record that encourages the entire feat?

BLAINE: I thought for the breath-holding it would be appropriate because there was already a record for that. But usually for the things that I do, a record doesn’t exist in books in the first place. Oftentimes, Guinness won’t partake because they require certain safety procedures built in. When I lived at Lincoln Center in the water tank, they wanted me to take a five-minute break every hour because it was the longest continual submersion in water. But because I wouldn’t get out of the tank during the seven and a half days, it’s not a Guinness record.

KIMMEL: Getting out and taking breaks would ruin the whole idea of endurance for you.

BLAINE: Exactly.

KIMMEL: I’ve met a lot of artists in my life, but I’ve never met one who takes as many risks as you do. There are a few other artists whose work revolves around acts of endurance. I know Marina Abramovi´c is a friend of yours. Are there other artists who have inspired you?

BLAINE: So many. First and foremost, I’ve always been blown away by those big public challenges that Houdini used to do. I’ve always liked artists like Chris Burden, who would take performances, put them in galleries, and then do things that were on the edge.

KIMMEL: What’s your favorite performance by Burden?

BLAINE: I liked when he had his friend shoot him in the arm with a rifle. [laughs] It’s pretty simple, but I’ve always admired that one. But he did so many amazing things—just lying between two buckets with live electric wires or living in a school locker for five days. I love all of that work.

KIMMEL: The thing is, if you did that on ABC, it would probably get panned.

BLAINE: Hell, yeah, it would. That’s for sure.

KIMMEL: What you do is art, and yet it has such mass appeal.

BLAINE: I think Houdini wrote the rule book on that. He said if you do something that’s death-defying and you put it in a public place where everybody can see it, then the people will come.

KIMMEL: Didn’t Houdini die doing a stunt?

BLAINE: He was a workaholic. He had a ruptured appendix. They aren’t sure if it was a ruptured appendix or internal bleeding from punches he took from some of his fans. In either case, he wasn’t feeling well, but he kept doing this water-chamber stunt that he did every night on stage. It was really difficult on him, and after a performance he was rushed to the hospital and died there. He just pushed his body too much. I think we take for granted our limits sometimes.

KIMMEL: On the subject of pushing limits, without giving it all away, what are you working on next?

BLAINE: It started because I had a dream one night that I was in a life-size bottle in the middle of the ocean. That’s where it started, and now I’m trying to work out how to make that into a physical reality—into a real physical feat.

KIMMEL: Is there anything that you have always dreamed of trying, but you think, There’s no way in hell I could do that? What is your biggest fantasy endurance test?

BLAINE: The one I’ve been obsessed with that I don’t know how it could be done is the sleep-deprivation record. It’s 11 ½ days. I was thinking I’d try to go one million seconds under test conditions, which is 11.57 days or something close to that. But I started experimenting, and for some reason it’s the hardest. I think you can build up a tolerance to sleep, but it’s a really difficult process, because your body recovers during sleep. Your immune system builds itself when you’re sleeping. So when I would do tests, I would be up for five to six days, and of course I’m hallucinating. But I also start getting these welts all over my body. I’m a superhypochondriac. So when you’re not sleeping, you start seeing things. And you think you’re dying of this disease or that disease. It’s really tricky on that end. But that’s one that I’ve been really obsessed with for a long time because it’s the scariest thing to me. When I was standing in that block of ice, I don’t think it was standing in one spot or the cold that got to me. The real thing that messed me up was the sleep deprivation. I began to hallucinate. I was out of my mind. It’s like you’re literally having nightmares and dreams, but your eyes are open.

KIMMEL: Finally, I wanted to mention that you do a lot of charity work. I don’t know if most people know this about you, but you’re one of the most generous people I’ve ever met.

BLAINE: I think, being a magician, it kind of goes hand in hand because it’s easy to walk into any hospital room or juvenile prison or classroom and pull out a deck of cards and mess with people’s minds and make them laugh. I go to this hospital in San Antonio every Thanksgiving called Brooke Army Medical Center. It has the number-one burn-unit ward in the world. I try to do magic for the guys in there. When you first go, they bring you into the amputee unit, and it’s really hard because they have these 18- and 19-year-old kids just back from Iraq, and they have no legs, no arms—nothing. It’s painful, but they bring you in there to break you in because in the burn unit you see some kids burned up to 97 percent of their bodies, where they have no fingers left, no ears, no toes, and they are in more continual pain than you could ever imagine. So I’d go in and hit everyone I could with magic and stay a couple of days. One time I went, this soldier, who was helicoptered in about three weeks before, wasn’t seeing anybody. He wasn’t letting anyone into his room and wouldn’t go out into the rehab unit. Sometimes it is the psychological damage as much as the physical. So I asked my friend Norma, who works at the hospital, “Is everybody okay? Did I get everybody?” And she said, “Well, there’s one guy, but he won’t see anyone.” I asked her to take me to his room.

KIMMEL: What happened?

BLAINE: The mother was in with the kid. Norma asks her if I can come in. She says, “Yeah, but he’s not going to want to see him. But sure. Bring him in.” The entire top of the kid’s head was burned and half of his face. But the half facing the door was untouched, and he was a really good-looking kid. I walk into the room, and I could tell he was just not having it. He doesn’t want to see me, and he’s not into it. I just grab his hand and start doing magic. I don’t act like he’s burned—I mean, physically I grab him and put a card in his hand. Because of the way I was treating him, he suddenly opened up a little bit and went from being stiff-faced to laughing, really following the magic. Nobody had touched his head because it was burned, but before I left I took my hat off and put it on his head. As I was walking out of the room, I could feel his mother crying. I was fighting back every bit of emotion I could. When I came back the next day, his mother came running up to me and said that as soon as I left, her son let the nurse get him dressed, and he went and joined the others in rehab. She said that little bit of magic opened him up, and he started doing what he needed to. When I went back the next year and took him out to dinner, he was so much better. They had done reconstructive surgery on his face, and he looked great.

KIMMEL: That’s amazing. Do you ever feel like that kind of work saves your life? Like it creates angels or something that watch over you when you risk your life for your projects?

BLAINE: Things like that visit remind you of what is important and what matters.

Menswear designer Adam Kimmel runs his eponymous fashion label in New York City.