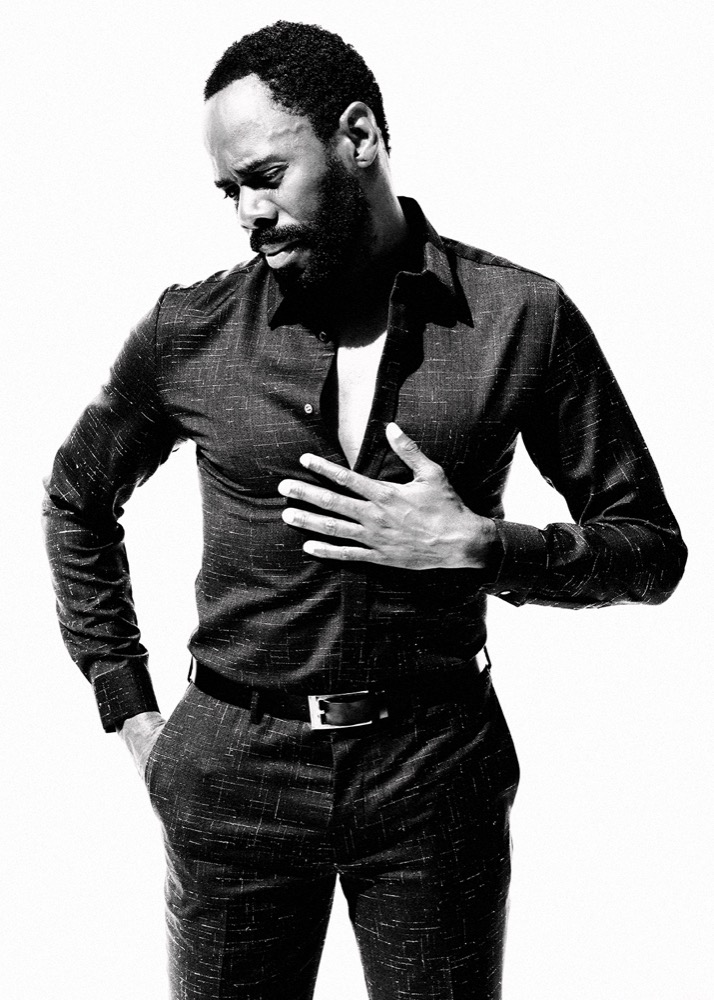

Colman Domingo

COLMAN DOMINGO IN LOS ANGELES, FEBRUARY 2016. PHOTOS: BRIAN HIGBEE. STYLING: LAURA MAZZA. GROOMING: NICOLE CHEW/ART DEPARTMENT USING JUARA.

The fifth episode of Fear the Walking Dead, AMC’s prequel series to the wildly successful The Walking Dead, opens with a stranger speaking. “Fire, earthquake, flood. You bought it all, didn’t you?” he says. “That’s not a question. I’m not asking. I’m telling you. I look at a person like you, and I know: You are a buyer. How do I know? Because I am a closer.”

Standing in a detention center wearing a ruffled tuxedo, the man takes his time over each word. He is smooth, smiling, confident, and callous. It isn’t clear how he is going to relate to the show’s protagonists—the extended Clark-Manawa-Salazar clan—but from the delivery of these lines alone, we know Victor Strand is going to be important. “Strand is a man of words,” explains actor Colman Domingo. “He’s got really good economy of language, especially in moments of chaos.”

Born and raised in Philadelphia, Domingo went to high school with Will Smith and studied journalism at Temple University. He began his career in the arts after college as a playwright in San Francisco and has been acting since the late ’90s. While the character of Strand is threatening to make the 46-year-old a household name, he’s been involved in plenty of prestigious projects over the last decade, from Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln (2012) to Lee Daniels’ The Butler (2013), Ava DuVernay‘s Selma (2014), and Steven Soderbergh’s The Knick (2015). Domingo’s theater résumé is equally impressive: He won a Lucille Lortel Award in 2009 for his autobiographical one-man show, A Boy and His Soul, and an Olivier Award for his role in The Scottsboro Boys, and has been nominated for a Tony, a Drama Desk Award, and a Fred Astaire Award. While he is currently in Mexico filming Fear the Walking Dead, which returns for a second season April 10th, his play Dot is running at the Vineyard Theatre in New York City. The story of a matriarch with Alzheimer’s, Dot has received rave reviews from the likes of The New York Times. Next up, he’ll appear in Nate Parker‘s Nat Turner biopic, The Birth of a Nation, which was picked up at Sundance by Fox Searchlight in January for a record-breaking $17 million.

Here, Domingo talks to his good friend and Selma co-star Tessa Thompson, who recently made her Off Broadway debut in Smart People with Joshua Jackson and Mahershala Ali.

TESSA THOMPSON: Hello, Colman.

COLMAN DOMINGO: Hello, how are you?

THOMPSON: I’m very well. This is my journalistic voice. It’s deeper and more serious.

DOMINGO: You’re going to pull a Barbara Walters.

THOMPSON: [laughs] No, I want to be Oprah circa ’93 in that interview she did with Michael Jackson. She asked all the questions that, at the time, America wanted to know and she asked them in such a way that you felt like there was no option but to answer the question truthfully. It was fantastic. I don’t know if I can do that over the phone—it’s something in the eyes— but we’ll see. When we met doing Selma, you were writing Dot, weren’t you? I was in your trailer and I read maybe the first 20 pages.

DOMINGO: It was Dot. I remember very clearly. What I usually do with my friends is say, “Hey, come check this out.” I think you used a set like that as well. When you had downtime, you were probably writing some songs in your trailer, right?

THOMPSON: I don’t think I was. That’s the thing that struck me about you Colman, to be honest. I was playing it cool, but I was just eating when we were doing Selma. I was just in my trailer, eating and diddling on my phone. I was not making any work. I was just thinking about this the other night at the opening of Dot at the Vineyard. I thought to myself, “Gosh, this was the little play that Colman was working on when we were doing that movie and now here it is, a real life thing that has an opening night and it’s brilliant and beautiful.” It really struck me. So, no, I don’t do that. I have not written anything.

DOMINGO: Are you not good at multitasking that way?

THOMPSON: I wish I were. I guess I’m just a bit haphazard about it. When you started writing Dot, was just in you and it had to come out or had you just decided “Hey, I’m going to write another play and I know what this play is about and I have some time off now in this trailer…”?

DOMINGO: Sometimes I get commissioned to write a play or musical, but things just want to come out; they tell me they’re ready to come out and I just start writing. Out of all of the things I’ve written, Dot was the quickest from first thoughts to full production. I started writing on set and then, when we were done, I went up to the New York Theatre Workshop for a week. You give me a week and three meals a day and I’ll finish a play. So I did that and the first draft was done and that was under nine months, which is really fast for a playwright and for a new play. Then I started getting offers for it to be produced pretty immediately. It’s been about a two-year turnaround. It’s in the zeitgeist. There are so many plays right now that have characters who are experiencing dementia or Alzheimer’s. Our Mother’s Brief Affair is a play that just closed with Linda Lavin where she had dementia. I think so many people are dealing with it in their families as they try to figure out how to support a person suffering from this tragic disease. Have you had any experience?

THOMPSON: I have. My grandmother died of Alzheimer’s and I watched my father and my aunt try to navigate how to care for her. My dad was away in New York City and my family lived in California. My father and my aunt respectively were just very different people, so it’s always interesting to see family members come together who are estranged trying to deal what’s going on currently.

DOMINGO: There’s so much conflict but also comedy that goes along with that. You take a very strong personality and you throw Alzheimer’s in the middle of it, it’s surreal and wild and dark and passionate and cheerful all at the same time.

THOMPSON: I imagine. I sat there thinking, “God, I wish my dad could be seeing this play with me because it would be this fun and cathartic thing to.” I think you’re right—there are so many people that are dealing with that in their families that people want to talk about it. What made you want to do that? Is it a personal thing?

DOMINGO: Somebody the other day said, “This is the last of a trilogy about Colman’s mother.” I don’t know whether to take that as a compliment or be offended by it because no, that’s not my mother, that’s my imagination. That’s me watching four different female friends of mine dealing with their mothers who had Alzheimer’s. But I guess it’s a compliment because people get so honest and real and gritty that they assume I’m writing from my personal experience. I wrote a play like that already. I wrote A Boy and His Soul that talks about how my mother had lupus and my dad dying of a heart condition. It makes me question the way people are able to see a work. Can they see it? Will they always see you as a protagonist in your plays? We’re people exploring things that we’re close to, [but] I’m not that egotistical to write plays about myself all the time. [laughs]

THOMPSON: Currently I don’t have the fortitude, but if I were to think about writing a screenplay or a play, it would be worrisome if things were personal. Was that ever an impediment when you started writing? The idea that you might let people know how you feel about things or if you’re talking about things that happened in your family?

DOMINGO: When I first wrote my solo play A Boy and His Soul, that was very honest and very much about my family. I would say maybe in 20 percent of it there’s some dramatic license. But I try to be as honest as possible and let the characters speak for themselves. My voice is in every single character. There are so many things that I say in Dot—about literary criticism, music criticism, how I feel about families, the choices we make and looking back on them, relationships, fighting for each other’s love or humanity—I’m like, “Yeah, that’s me. In every mouth of every character.” But I actually wanted to put a character of myself in in this play, and I’m an offstage character named Jason. That’s my middle name. I want you to know that I’m the storyteller. I find that interesting. When I first did A Boy and His Soul, my parents and siblings were more like, “Wow, people will care about a story about us, and about what we’re interested in and thinking about and how honest we are?” I was like, “Yeah, that’s the whole point—because you are so honest about your expression and the way you live your life.”

THOMPSON: The thing that struck me so much about watching Dot was that you got to see this black family that was so many different kinds of black people inside one family and it never felt self-conscious. It was what families are like.

DOMINGO: I think that most people don’t see those families on stage.

THOMPSON: I hadn’t. For you, is that something that feels intentional or political? Or, “That’s what my life looks like, so I write what I know”?

DOMINGO: I started writing because I saw such a huge lack of complex stories about the inner city. Anything I would see at the theater, it’s all about poverty, drugs, abuse in the black home. I didn’t come from that home and I’m from the inner city. I grew up with people who went to Martha’s Vineyard as well as people who sold crack cocaine. [laughs] These people can all come together in the same house and enjoy one another.

THOMPSON: Did you know any people that did crack cocaine in Martha’s Vineyard? Was there any convergence between the two? I want to see that one man show.

DOMINGO: That’s probably my next play. I really try to set up my plays so that people are thinking, “Oh, you’re starting with a stereotype.” Have a loud, brash, street talking girl who’s just so colorful. I know that sister, she’s absolutely real. And then I smash that stereotype and we see the heart of this person as well. The gay couple in the middle of the play, it’s a very light, contrived argument that they’re having about a juice cleanse and then I smash that stereotype when we get to the heart of what they’re actually dealing with. I like setting up each archetype and then just punching sticks through them. “Oh, you think it’s going to be this type of play? Gotcha!” [laughs]

THOMPSON: I’ve always found the idea of doing a one-man show or a one-woman show completely terrifying. Is it terrifying?

DOMINGO: It is because it’s honest and stripped down and bare and there’s no one else to give the ball to. It’s the relationship between you and the audience only and it can change every single night. I wrote that back in 2005 as a challenge myself. This was when I was still bartending and I wanted to do something. No one can tell you not to create. At any point you can be creating, so I chose to start writing when acting work wasn’t available, or writing wasn’t available. I think writing a solo play was the most liberating thing I ever did. Writing something for yourself that’s truly what you feel about art and creativity and putting that out into the universe saying, “This is my message to you, my gift to you.”

THOMPSON: I imagine it as taking agency: “This is the kind of story I like to tell and if it’s not available for me then I’m just going to make it.” When I Googled you in preparing to ask you questions and try to embarrass you, I realized all this stuff—for example, you have a Fred Astaire nomination for Best Principal Dancer on Broadway.

DOMINGO: I don’t know how that happened.

THOMPSON: That’s so serious. I just assumed that you were my friend who was a good dancer, [but] that means that you were nominated against people who, that’s their life—they’re Broadway dancers.

DOMINGO: Completely, but awards are so subjective. The idea of being a Broadway singer and dancer is still odd to me. I always thought I was an actor who was game. I’ve been in the circus, I’ve learned commedia dell‘arte, Shakespeare, you name it. I’m always up for a challenge. I’ll sing it; I’ll learn what I can learn for the show.

THOMPSON: Is that something you wanted to do as a kid? Did you want to grow up and perform?

DOMINGO: No! No. I was shy.

THOMPSON: What did you think you were going to do?

DOMINGO: I don’t know. No one through elementary school to high school would have thought that I would have the career I have. I was nerdy. I wore my sister’s hand-me-down PRO-Keds. I was a pimply-faced geek. I was always doing the school newspaper and I had this little camera around my neck all of the time. I was a photojournalism major [in college]. I’ve always thought I was a voyeur; I wasn’t someone that was going to be on the screen or on the stage. I was not in high school musicals or plays or anything like that. I was watching. But I guess that’s been my journey, watching human behavior, because that’s what we do.

THOMPSON: That’s so funny. I used to think I wanted to be a journalistic photographer and I studied cultural anthropology for a while. I thought I’d be an anthropologist but the fantasies that I had concocted for myself in that profession were total fiction. They were like movies.

DOMINGO: Oh yeah, I was picturing going to war-torn countries and taking photos.

THOMPSON: Exactly. [laughs]

DOMINGO: At one point, I wanted to be an archeologist because I was obsessed with Ancient Egypt and the idea that black folks had any contribution to the world, which I did not learn in school. By the time I stumbled upon ancient Egypt I was like, “I want to be an Egyptologist.” So we both have careers that we didn’t think we would have… but you were in plays and stuff in school.

THOMPSON: Yeah that’s true. I remember overhearing David [Oyelowo] when we were working on Selma say that when he knew he was going to play Dr. King, he knew that he needed you by his side because you guys worked together on Lincoln. Then I remember running into Nate Parker in L.A. before he went to Sundance with The Birth of a Nation, and I said how excited I was about Birth of a Nation. He knew that you and I were friends and he said, “I just knew I needed Colman.” How do you manage to position yourself as somebody that, when someone is about to do a big undertaking, they need by their side? Do you feel like those relationships happen organically?

DOMINGO: That’s nice and I’m so grateful. I do consider myself to be a generous actor, and I really seek out the generosity of other actors. If felt like a spiritual thing—I needed to be there holding David’s hand praying with him as Ralph Abernathy to his King before he did his speech, and make him laugh like I did, as I know that Abernathy would have for King. For Nate, we didn’t even work together on Spike Lee’s film Red Hook Summer; we met each other when we were at Sundance for the film. We just admired each other so much. I was doing a play in New York and he came and saw it, and right after that we went for a drink and he told me this film that he had that wasn’t even financed yet, and he said “Brother, I want you to be with me. I have something for you.” I was the first person he cast. I think what we find in each other is brotherhood more than anything. He knew that I would be there for him. He didn’t have to worry about me. I’m a hard worker; I’m a huge advocate for his work, and for him to branch off into becoming this extreme polymath—producer, director, writer, actor. I knew he could handle himself, but I knew I’d be there for him as well. I’m so proud of Birth of a Nation and what Nate has achieved.

THOMPSON: When you watched the film at Sundance, did it feel like the film that you guys made? While you were making it, did you think that this was something special?

DOMINGO: I felt that it was something special. I’ve played a Union soldier in Lincoln, head of the White House butler staff in The Butler, and even marched with Selma, but the idea of playing a slave who was going to be a part of this rebellion…I was living in so much darkness for the first couple weeks and I had to really work it out. We were shooting on plantations, and you feel that emotional trauma. It’s in the soil; it’s in the air. I was in such a dark space. Me, Aja [Naomi King], Chiké Okonkwo, and Penelope Ann Miller, we bonded. We would come together a lot because we all need each other so much. I felt like I was navigating so much emotionally that I really couldn’t tell what it was going to be. All I knew was that we were trying to be as honest as possible.

THOMPSON: I remember FaceTiming with you when you were in your trailer. You were wearing a necktie and making fun of yourself because you thought you looked really scruffy, but I thought you looked very dapper even in your dirty slave clothes.

DOMINGO: I look at the film and there’s a rawness to it. I think it’s a beauty because it’s so stripped down and bare. I look at myself in the film and it doesn’t look like me. I don’t think it’s one of those things where it’s like, “Oh, he’s transformed so much. Look at what makeup and costumes did.” I just don’t feel like myself in that. I’m a happy go lucky person. I’m a bit of a Pollyanna. You know that. [laughs]

THOMPSON: Colman Domingo, is that your name real? [laughs]

DOMINGO: Yes it is.

THOMPSON: What’s your middle name?

DOMINGO: Jason.

THOMPSON: Jason seems out of place with Colman Domingo.

DOMINGO: People constantly think I made it name up. I don’t think I’m smart enough to create a name like that. It’s just so outrageous. Especially being here in Mexico now shooting Fear the Walking Dead, people are confused. They’re like, “Where does Domingo come from?” Clearly you don’t speak Spanish and you’re black…” There are a lot of complications with that, people! My father’s from Belize and his family is from Guatemala. My friend Robert O’Hara is a playwright, and his joke is that when people say “Oh, where do you get a last name like O’Hara?” he’ll just say, “Slavery.” [laughs]

THOMPSON: Which is entirely true. They’re all made up names. The Walking Dead is such a cultural phenomenon. Is it in Mexico? Do people know what you’re doing there?

DOMINGO: We’re part of this enormous franchise. I had no idea when we joined the show. It’s a world phenomenon. AMC Global… They’re in every market pretty much. I feel like they’re hiding out in my mom’s basement. They’re everywhere.

THOMPSON: When you were in the process of getting the role, was it top secret and shrouded in mystery?

DOMINGO: It was one of the simplest things. I had just joined this agency that I am with now and it was the first audition I went out on. My agent was very gung-ho about my audition; she was very excited about this new show. I was like, “I’m not interested in zombies” but then I opened up the sides for this character of Strand and I had never read anything like it. It was like Shakespeare. It was a monologue that would introduce my character. I thought, “This is kind of cool.” I threw on a suit and I put myself on tape at home. I did it so quickly. I ran the lines the night before because it was extremely well written. I sent it off and didn’t think about it. Now at this time, I was being looked at for The Get Down, the Baz Luhrmann series on Netflix. The next week my agent called and said, “There’s some good news, but there’s a complication. Baz Luhrmann really wants you for The Get Down, but you’re getting an offer for Fear the Walking Dead.” I had to make a choice and the artistic part of me, meeting with Baz Luhrmann and him showing me storyboards, I was so game for that. But, at the same time, I was at a place in my career where I wanted to take a leap and do something I thought I would never do. I am now on the set of Fear the Walking Dead and having the time of my life.

THOMPSON: Were you ever nervous joining a franchise with such rabid fans? Was it a weird universe to enter into?

DOMINGO: I think I’m still a little unaware. I do understand that possibly. I get these kind of blue-collared guys on the street yelling out me because they feel a brotherhood. It’s cool. The fans are really kind and generous. They’re rabid in all of the great ways. Have you ever watched The Walking Dead? Are you interested in zombies? Did you ever want to be on a show like this?

THOMPSON: I have watched some of it. But it kind of scares me, the whole zombie thing. As an actor you can die at any minute. Is that fun or is that frightening?

DOMINGO: I try not to think about it. What I do is I surprise my writers with good chocolate. [laughs]

THOMPSON: Edible Arrangements.

DOMINGO: My character, Strand, comes in episode five. Your character in Westworld—

THOMPSON: Is the same way. I told you that I watched your introduction to be like, “How do you navigate starting mid-season and communicate to the audience from the onset that [the character] is going to be important to the audience?” I watched you just completely massacre this scene in the jail and then I was like, “I can’t watch this for a minute. I’m intimidated now because Colman is doing so well.” I had no idea what was happening but I thought it was very riveting whatever you were doing.

DOMINGO: I didn’t know what was happening in the episode before. I had no knowledge of anything. All I had was my first scene.

THOMPSON: I know and I was shocked. I’m such a nerd because when I’m working on something like that—like when I was doing Creed, I went back and watched all the other Rocky movies. I tried to understand how Adrian relates to the universe of Rocky. You felt like a gunslinger when you were just like “I had what I had.”

DOMINGO: I would have been intimidated if I knew too much. Of course I’ll learn my lines and know what’s important, [but] I sort of looked at it like Fear the Walking Dead is actually a show called “Strand,” so all I’m thinking about is what I need my needs are and my world. That is hopefully what will make good drama. I had no idea what was going on with Frank Dillane’s character Nick. He would walk around with a limp and I would be like, “What’s wrong with his leg?” [laughs] To know only what the writers have given me and have that as my absolute truth, I think that’s exciting. Whatever comes in the moment I’m playing off in a very real way.

DOT IS RUNNING AT THE VINEYARD THEATRE IN NEW YORK CITY THROUGH MARCH 24. FEAR THE WALKING DEAD RETURNS FOR A SECOND SEASON TO AMC ON APRIL 10. THE BIRTH OF A NATION WILL COME OUT THIS OCTOBER. TESSA THOMPSON IS AN ACTRESS AND SINGER. HER RECENT PROJECTS INCLUDE THE FILMS CREED, SELMA, AND DEAR WHITE PEOPLE AND THE PLAY SMART PEOPLE. SHE CAN NEXT BE SEEN IN HBO’S WESTWORLD AND THE WAR ON EVERYONE.