Writing

Claudia Rankine Tries to Answer the Impossible

Claudia Rankine’s new play, Help, begins with a casual exchange between two strangers standing in line at the airport. One is a white man, the other a Black woman. In this isolated moment, the way they speak to, through, over, and against each other—extraordinary in its implications precisely because it is so ordinary—becomes a runway for Rankine’s radical, undaunted exploration of the fragile, fearful mind of white men. Rankine is, of course, one of America’s most celebrated poets—no single book of poetry published in the 21st century has managed to become required reading for the culturally astute the way her 2014 collection, Citizen: An American Lyric, has. But her play Help tackles race not so much from the vantage of defining Blackness, but instead, tries to drill an eyehole right into the heads of white men. In doing so, Rankine doesn’t so much turn the tables on the subject of race as show the table for the obstacle it is. The play treats white men as objects of study, the very way Black bodies have traditionally been treated in culture, a gambit the play’s narrator admits early on: “Did you hear the one about the white man who walked up to a line, tried to make conversation only to enter the same reality as a Black woman?”

Help originally premiered at New York’s The Shed in March 2020, but it only managed two performances before COVID dropped the curtain. This spring, with a few tweaks and revisions by Rankine, Help is back on, a contemporary Greek tragedy set in the liminal nowhere spaces of airplanes and waiting lounges. What the play’s narrator seems to crave the most is an honest conversation, the very one white Americans have been taught to avoid on matters of race. This past December, Rankine met her friend, the writer Andrew Solomon, at The Shed’s café, for an honest conversation about race, homophobia, interracial relationships, and the constant fear of violence. —CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

———

ANDREW SOLOMON: I read your play last night and was deeply moved by it.

CLAUDIA RANKINE: Back in 2020, we were in previews three days before the world shut down. I felt very lucky that we had two performances. But all those people who worked really hard on the production never saw what they made. Now we’re bringing it back almost two years to the day.

SOLOMON: I’m wondering if it felt different on stage than it did as a script. Do you think people were getting the messages you were sending?

RANKINE: To me, it’s self-evident that we are in a democratic crisis, that white supremacy is not only on the rise, but is also empowered. One of the actors said that the white men he had invited to see the show really resisted it when they saw it. And then after January 6, his friends came back to him and said, “Oh, I get it now.” So there are some of us who have been watching, and some who have been blind to what’s happening all around us.

SOLOMON: It reminds me of when I was reading about the relationships between Black and white artists in South Africa. I don’t know if you’ve ever met Barbara Masekela. She was sort of serving as the portal to Nelson Mandela for a time. She had once been on a flight to South Africa, and the flight attendant came and served lunch to the man on her left and the man on her right. And then went to the next row. She’s a powerful force of nature, this woman; she’s not a little shrinking violet. And she said to the flight attendant, “Excuse me, but are you going to bring my lunch?” And the flight attendant said, “I’m so sorry. I didn’t see you there.” I remember thinking at the time that the end of apartheid will readily undo certain restrictions and obstacles to equal opportunity. But there is a whole other part that involves not being seen when sitting in a row of three seats that will take much longer to resolve.

RANKINE: Exactly! And I wonder if it can be resolved. Because you’re talking about a culture of people who get their sense of possibility and importance from my invisibility. It was the same experience in this country with the changing of the laws of the Voting Rights Act. That didn’t change people’s sense of who people of color are. And look at Congress today. We’re one senator away from shifting the Senate back. It’s hard to be optimistic about the American public when so much is in place to empower a certain group of people.

SOLOMON: It’s easy to indict Trump. But when you get to the section in your play about your husband, I thought, “Oh, wow. Okay.” I too felt indicted. It isn’t that I felt defensive exactly, but I thought, “I understand the problem. And I see the connection. What are we supposed to do now?”

RANKINE: That’s the thousand-dollar question. So many people want to locate the resistance to democracy in the body of Trump and his followers. But in the play, I quote the filmmaker Whitney Dow, who talks about the fact that for him as a white man, he’s had to recalibrate the narratives that he’s grown up with relative to who he is—who white men are. I think about you, for example, and the story you once told me about always wanting to have another place to live. Having the sense of authority and possibility to be able to go to England, to set yourself up there, that comes with a certain sense of support in the world. And so many of us don’t have that, no matter what our upbringing has been. So I think it’s what you do with that power. You have it, the power and the glory.

SOLOMON: And the kingdom. [Quoting the Lord’s Prayer, a verse used in Help]

RANKINE: It’s what you do with it, at the end of the day, that matters. But you have it.

SOLOMON: Tell me about being married to a white man. Does it create a sense of crisis like the one described in the play? I don’t want to turn it into a personal narrative about him, but is he able to do whatever it is that we should be doing with our privilege and opportunity?

RANKINE: I think John [Lucas, a photographer and filmmaker] has lived the kind of life that has been very self-conscious about his privilege, which is not to say he doesn’t understand that he can use it. He does use it. Sometimes it’s on full display, unconsciously. But he’s one of a few people I am in close contact with who I have been able to watch attempt to bring equity to the spaces around him. And that is not because I’m married to him. I think that’s why I’m married to him. You can point it out to him. My daughter, who is obviously mixed-race, points it out to him!

SOLOMON: Does she identify as mixed race?

RANKINE: I think she identifies as a Black woman. There were times when she was younger when I think she would’ve said, “I identify as mixed race,” but as she has gotten older, I feel when she speaks, she speaks of herself as a woman of color.

SOLOMON: What do you make of the argument about whether the left is closing down speech as much as the right? I’ve never worked out quite where I am on the free expression of hideous ideas. I think it’s a complicated question. There’s that quote, erroneously assigned to Voltaire, that goes, “I disagree with what you say but will fight to the death for your right to say it.” But I’m concerned when some of my godchildren, who are in college, say, “I feel like I can’t really say this, or I can’t write on this topic.” Where do you stand on that?

RANKINE: I have spent my entire life inside of academia. And as far as I can see, the interrogation of everything should be on the table. If it’s shut down on one side or the other, it serves no one. I’m not interested in silencing people. But I am interested in creating environments where people feel safe. And I do believe that there are certain kinds of discourse that are intended to harm. In that case, people should have the option to opt out of those situations. But as much as we can trust in civilized discourse, I’m not after full agreement or necessarily any agreement with other people. I don’t think that fosters any kind of progressive knowing. Will I invite identified white supremacists into my house? No, I will not. Will I accept invitations from Fox News? No, I will not, because I don’t believe they’re interested in engagement.

SOLOMON: How do you reconcile this question of erasure with the fact that you’re in the privileged status of having an education and reasonable economic security?

RANKINE: In my last book, Just Us: An American Conversation, I intentionally brought myself and my life fully forward in order to say, “It doesn’t matter what it looks like.” If I have the same education that you have, it doesn’t mean that we’ve had the same experience getting that education, it doesn’t mean that the road traveled was any less difficult for me, because the issues we’re talking about are institutional. I’m not pretending that I have felt the worst of it, but in Just Us and my play Help I wanted to say, “Let’s take economics off the table. Let’s take capitalism off the table, and look at racism for what it is.” It’s your understanding of who you are and who I am, and my understanding of who you are and what I want.

SOLOMON: Do you experience the world as a hostile place?

RANKINE: I experience the world as a complicated place and it takes management. I’ll tell you a great story. I was in the airport, and I walked up to the first-class counter, and a woman came running out from behind the counter and said, “Miss, miss, you’re in the wrong place.” There’s a long line of people. And she says, “Economy is down there.” And I said, “No, I can read.” And she said, “Let me see your ticket.” So, she takes my ticket, and people are laughing in the line, and she’s embarrassed. I was heading for the end of the line, but now she’s like, “Go over there. Go to that lady over there behind the…” So now, she’s put me in the front of the line. She sent me over to the next woman at the counter. So, the woman has seen all of this, is suddenly incredibly nice and says, “There’s a lounge you can go to.” She takes my ticket, but I’m pissed. I get on the airplane, and there are three white women on the other side of the plane. They’re talking, looking at me, and they’re pointing. So, I’m thinking they must have heard what happened. And then, finally, one of them comes over to me and says, “You’re the poet, aren’t you?”

SOLOMON: Oh, that’s a sweet story in the end.

RANKINE: Exactly. All of a sudden, the world just turns.

SOLOMON: I feel, even for me, the sense that other people may be reacting to me in a particular way because I’m gay. For example, my husband had surgery last week that didn’t go entirely as planned. We went to see a doctor yesterday and I felt like, how much am I going to have to explain who I am and why the two of us are coming in together? And I thought, we’ll just get it out of the way. And so, I said, “It’s so nice to meet you. I’m John’s husband. He’s been having a rough time.” My primary assumption is that the doctor couldn’t care less, and that it was all totally fine, and I didn’t even think that we would get a lower standard of care. But I thought, is he going to be one of those people who slightly dreads having to deal with people like us? I feel like that possibility is always there.

RANKINE: Yes, one of the privileges of my life has been to live in New York and California, where you just take certain things for granted and people’s capacity to hold difference is something that you rely on. But there’s always someone. And I often wonder what the defense is, what people are fighting within themselves when they’re homophobic, when they’re racist. What are you afraid of? What are you holding that this needs to happen right now?

SOLOMON: I’m always shocked by the stories I hear, and at an earlier stage in my life, my gut response was, “That isn’t what they really meant, you must have misunderstood.” It seemed implausible that people would be that frankly and directly homophobic or racist. Once a beloved friend sat me down and said, “You have to stop telling me when I tell you I’ve experienced racism, that it wasn’t really racism or it wasn’t that bad or that serious.” And she’s right. One of the things that your play does so powerfully is to narrativize that experience to the point where it becomes absorbable and comprehensive. Because I think for well-meaning liberals who are brought up to be colorblind, it’s frequently difficult to take on board the Black experience. I don’t think just because white people understand the Black experience, the Black experience will get better as a direct and immediate consequence. But it does seem like a step in that direction. In your play, are you writing for the typical white man to undergo a transformation? Are you writing for people who will identify with the narrator?

RANKINE: I’m often asked this question: Who is the intended audience? I’m being honest when I say I don’t have an intended audience. When I started working on Citizen, it was like doing a math problem. Can you get down on paper something that lasts a second or ten seconds? Can you capture it in language so it’s seeable? That was the mission. And that took me through years of listening to stories, figuring out what word can drop down historically. I wasn’t thinking an Asian girl might read this and think, “That’s how I’m treated.” Or a Black woman might read this and think, “That happened to me,” or a white person might read this and think, “I’ve done that.” I was thinking, “How good are you? Can you do this?”

SOLOMON: You can.

RANKINE: It turns out language can. Language can hold it.

SOLOMON: I have close friends who are an interracial couple. And I went and interviewed them about their experience for the book that I’m working on, having known them for years. They were quite keen to talk about it. Stephanie said, “I said to Doug, when he said he wanted to marry me, ‘You’re going to give away social capital if you do that.’ And Doug didn’t really seem to understand what I was talking about, and I said, ’Just make sure you’re prepared for what you’re giving up in doing this.’” I was, again, naively shocked by that because Doug seems to have plenty of social capital and Stephanie is fabulous and the two of them have a great marriage and lovely kids and all the rest of it. Did you have any sense of that when you got married?

RANKINE: I did, because when I was in college, I dated a guy whose parents were very aggressively disapproving of the union. We had gotten to the point where we were engaged and the mother did an interesting thing where she threw an engagement party and then locked herself in the bedroom after arranging the whole thing.

SOLOMON: Wow.

RANKINE: And then another moment she said to me, “If you really loved my son, you wouldn’t marry him, and you will devastate the life of your children.” I mean, she was committed. I didn’t marry him, but not for those reasons. It was just not the right time. But by the time I married John, I had obviously encountered resistance to these kinds of unions and his family helped in their own way to make the marriage possible because of their ability to treat people as people.

SOLOMON: What are you writing now?

RANKINE: I’m working on a film. But honestly, it’s been hard to write anything after January 6 of last year.

SOLOMON: I think for a lot of us January 6 was the point where we realized that things aren’t necessarily going to get better. They might only get worse. I remember a revelatory moment in Afghanistan when I was reporting in Kabul, someone showing me a photo album from the 1960s of women wearing miniskirts. We tend to think the burqa is a primitive garment. But it was introduced there after the move for liberalism. And I always feel that something similar could happen here.

RANKINE: Yes, it could. But in terms of writing, I’m waiting for something. I don’t know what it is. It could either be good or bad. It could create an avenue of possibility in terms of a line of inquiry, in terms of my own thinking and writing—or it could be a cry for help. I don’t know.

SOLOMON: Help, the title of your play—is it an imperative? A description? A plea?

RANKINE: It’s all of those things.

———

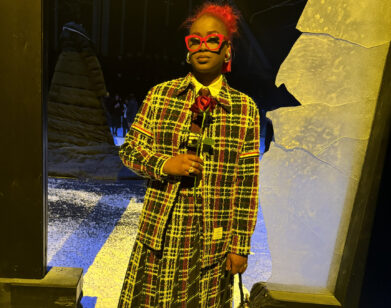

Hair by Skin Arima using Oribe at Home Agency

Makeup by Tracy Alfajora

Production by Perris Cavalier at The Morrison Group