Camille Rankine’s Poetic Structure

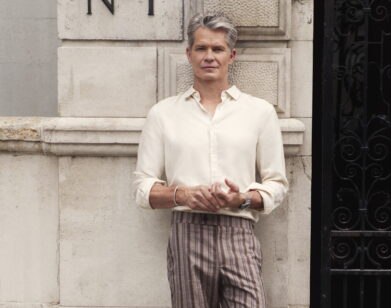

In her debut poetry collection, Incorrect Merciful Impulses (Copper Canyon Press), Camille Rankine dives into the ocean, city, and memory, through webs of lineage and isolation to deliver poems as symptoms, still lives, letters, and instructions. With a compassionate voice, she challenges us to look and re-look at the world around us. Lauded by poet Cornelius Eady, Rakine has roots in Jamaica and the Pacific Northwest. Where others shy away, Rankine leans in closer, takes space.

Last night, Rakine read from her collection at McNally Jackson in SoHo, New York as part of The Poetry Society Readings. We spoke with the New York-based poet about the intersection between music and words, how the static of sea or metropolis makes its presence felt in poetry, and moving past society’s veneers through art.

SARAH HERRINGTON: What is it you can communicate in poetry that you can’t otherwise?

CAMILLE RANKINE: I think poetry is a way of saying the things you can’t say in everyday conversation. At least, not without getting a lot of strange looks and making people very uncomfortable. In America especially, there’s a sort of social contract to be pleasant. Someone asks you how you are, and they’re usually just asking you to tell them you’re okay. I’m okay; you’re okay. That’s how we speak to each other, generally. Poetry is a way of burrowing beneath that veneer and getting to something a whole lot messier. And life is a very messy and complicated thing.

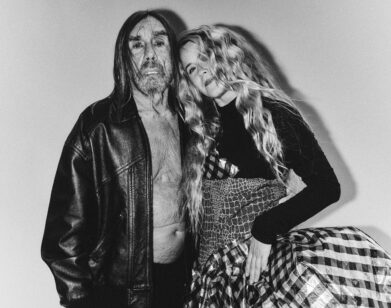

HERRINGTON: You also sing with the band Miru Mir. What is the relationship the voice when singing versus on the page?

RANKINE: Music is a big part of my life and in my writing. I’m very much driven by sound and rhythm when I’m putting a poem together, but writing lyrics is such different exercise. I’m so used to the words doing all of the work, but with lyrics, you have another mode of communication doing all this work for you—the music itself—and you have to listen to what it’s telling you, allow it to say its piece. For me, as a poet, a lot of the time that means getting out of the music’s way.

HERRINGTON: What one or two songs might be the soundtrack of this book?

RANKINE: I have so many musical obsessions, it’s difficult to say! But I do find a sort of familial sympathy between this book and “Eight Minutes,” a song about the end of the world that’s on my brother Jerome Rankine‘s latest album. We’re both a bit preoccupied with the apocalypse, and the book is definitely infused with a sense of impending disaster. Along those lines, another piece that comes to mind is William Basinski’s “Disintegration Loop 1.1,” which a friend I met at The MacDowell Colony brought to my attention—he played it one night while a bunch of the fellows gathered on the lawn to watch the Perseids. I loved it so much I played it in my studio while working on finishing the collection. Apparently Basinski finished the piece on the morning of the September 11 attacks, and listened to it during the last hour of daylight on a rooftop in Brooklyn, watching smoke rise from the city.

HERRINGTON: Which makes me think of this line I loved: “In the city the climate is hostile, which suits me.” How important is place in both the theme and creation of your art?

RANKINE: I grew up between Portland, Oregon, and Jamaica, so the ocean has always been a presence for me, and the landscapes in which I feel most at home are lush and green. Now I live in New York City, and it is neither lush nor green. I don’t know if I write differently in one place versus another, but both landscapes are very present in my psyche always, and both are present in my work. There’s a tension between the natural world and the manmade in the book that springs from that.

HERRINGTON: Speaking of human-made…I’m always curious how poets order and group their collections. Can you speak about that process?

RANKINE: I’m not a person who writes toward the container of a book, so at certain points along the line, I would pause and take stock of where I was, what I had written, what themes were forming among the poems. Eventually, I could sense common concerns threading their way throughout these individual poems, and I began to see them coming together as a collection. While in residence at MacDowell I started really putting it together; figuring out which poems belonged and which didn’t, what they were saying, what still need to be said. As I worked on ordering the collection, I thought about where I wanted the poems to begin in terms of outlook, tone, and emotional landscape, where I wanted them to travel, and where I wanted them to arrive in the end.

HERRINGTON: This collection is dedicated to your parents and their parents, and you mention this connection to your brother’s art, too. How important is lineage in your work?

RANKINE: I dedicated the book to my parents and grandparents because I wanted to say thank you, and because they are such an instrumental part of how I see and understand the world. Growing up in America with Jamaican parents, I’ve always existed a bit in between two different worlds and cultures, and the expectations of both. I think that point of view comes through in the book. The poems are asking how the individual fits into their social context, how they understand their history, and how history informs their present and future. These are questions I’ve grappled with throughout my life.

HERRINGTON: Can you talk about these poem types? Symptoms, Still Lifes, Letters (dear dear dear), Instructions.

RANKINE: There’s a lot I could say about each! The “Symptoms” poems are perhaps the most significant presence. I see them as a way of examining our tendency to quantify and pathologize our behaviors. I like how they introduce the idea that the speaker in the poems is suffering from a wrongness that must be diagnosed and corrected. That clinical outlook also comes through in the “Instructions” poems. The “Still Life” poems operate a bit differently. I was attracted to the idea of stillness, and the traditionally quotidian nature of the still life in visual art. I think of the speaker in the still life poems as struggling within that stillness, within the relentlessness of the everyday. And yes, the epistolary poems are all about “you.” For me they have a way of introducing the idea of different addressees—there’s a lot of “you” throughout the book, and here they are identified; patriot, catastrophe, night, enemy. I like the possibilities they give us for who is being addressed throughout. They trouble the notion that it’s just one other.

HERRINGTON: What is the role of isolation—a kind of modern isolation—in the themes of this collection?

RANKINE: I think the speaker in the book is bewildered by the world and trying to figure out how to place themself within it. They try to relate and connect to those around them, but they also have a great amount of ambivalence and fear about those efforts—an ambivalence and fear that comes from being human, but also comes from being a human living among other humans with ideas about who does and does not belong among us, who should be welcomed and who should be shunned. It’s a modern sort of isolation, but also one that is informed by history, and all the things that have happened in the past to lead us here.

HERRINGTON: Also, I love the line “I have come here to make seen the day I see” to me, this is—at least part of—writing.

RANKINE: That’s from one of my newer poems, actually! I like to remember that we’re not all experiencing the world from the same perch—not seeing the same day—and that’s one thing poetry can offer: the opportunity to see the world in a new way.

CAMILLE RANKINE’S NEXT NEW YORK READING WILL BE AT THE NEW SCHOOL ON APRIL 20, 2016. FOR MORE ON RANKINE AND ADDITIONAL READING DATES, VISIT HER WEBSITE.