Gilles Mendel Goes to the Ballet

SKETCHES AND COSTUMES BY GILLES MENDEL FOR CALL ME BEN

Call Me Ben, which premiered this past weekend, is one of the more exciting, progressive performances of the New York City Ballet’s Architecture of Dance festival, which inaugurates the 50th anniversary of Lincoln Center. Helmed by Ballet Master In Chief Peter Martins, the series is a cross-medium, pan-generational collaboration between the world’s leading artists in their respective fields of composition, design, and choreography. The result: seven new ballets and four commissioned scores set to premiere over eight weeks, most of which occur on stages created by accolade-wealthy-and-worthy architect Santiago Calatrava. And Call Me Ben, a theatrical and balletic retelling of gangster and Las Vegas pioneer Bugsy Siegel, is the performance that breaks most aggressively from the conventions of traditional ballet.

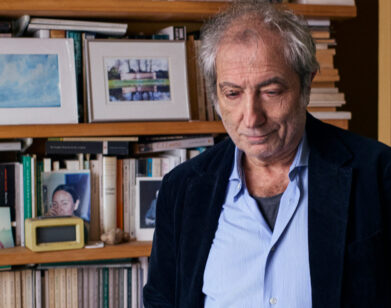

Call Me Ben also, unsurprisingly, is the performance put together by the festival’s most motley crew of collaborators: Melissa Barak, a young, former NYCB dancer, and the only female choreographer; a score commissioned from 19-year-old musical prodigy Jay Greenberg; and designer Gilles Mendel, of J. Mendel, whose work in couture and ready-to-wear, like this ballet itself, highlights tradition through subtle, exquisite departure.

Greenberg’s score is at times both explosive and smoldering, deadly serious and comical, like a gun pointed at your face that finally fires a flag that reads bang! The narrative move by Barak to use the Bugsy story is a bit of contemporary ingenuity, and inviting of a much younger audience. For a backdrop, Calatrava’s scene of towering palm trees, gradients of desert reds and yellows, and a deep, star-filled sky, recreates a time before Hollywood and Vegas’s views of the heavens were blanketed by smog and sin.

“It feels the same way as when I have an actress come into my studio,” Mendel says of his first foray into designing for a narrative. “You put them into character and they transform themselves. An actress in real life doesn’t look the same way she looks on TV or in the movies. But you put them in character in the studio and they transform, they become this actress that you dream about. And I feel that with the dancers, it’s exactly the same magic…The moment they put the clothes on, it elevates them. You and I, regular people, we don’t have that, we’re not trained that way. But the first time I put one of the dresses on one of the ballerinas, I was petrified, I said ‘Oh my god, her hips are wide and her torso is long, but she has short legs; how is this going to work?’ And then she went on her toes, she pointed with her pointy shoes, and the dress become completely transformed, it was spectacular.”

Mendel’s pleated silk dresses are figure flattering and flow like the sacramental wine that slipped through prohibition, cascading through the air with soars and flourishes all their own, as if the dresses themselves are dancers. They are not in any way diluted for costuming; they are the impeccable work of a couturier. For the menswear, Mendel went for full authenticity, using archived Loro Piana gangster fabrics in heavy-stripes and even heavier wool, and declining to put anachronistic vents in the coats, as such a thing didn’t exist at the time. Brilliantly, Mendel devised a sort of accordion mini-vent under the suit arms that would allow for dexterity and a balletic breathability, ultimately creating a perfectly tailored slim fit. The men on stage look elegant and pristine, even while flying through the air or throwing wild haymakers. A gangster slumps over shot dead, his dream of Las Vegas just beginning to boom, his style and city some sixty five years later still thriving, reminding us that the best traditions are the ones that survive long enough to be considered evolution.