Artist Cory Arcangel Dives into the New Web Series CULTURESPORT

CULTURESPORT

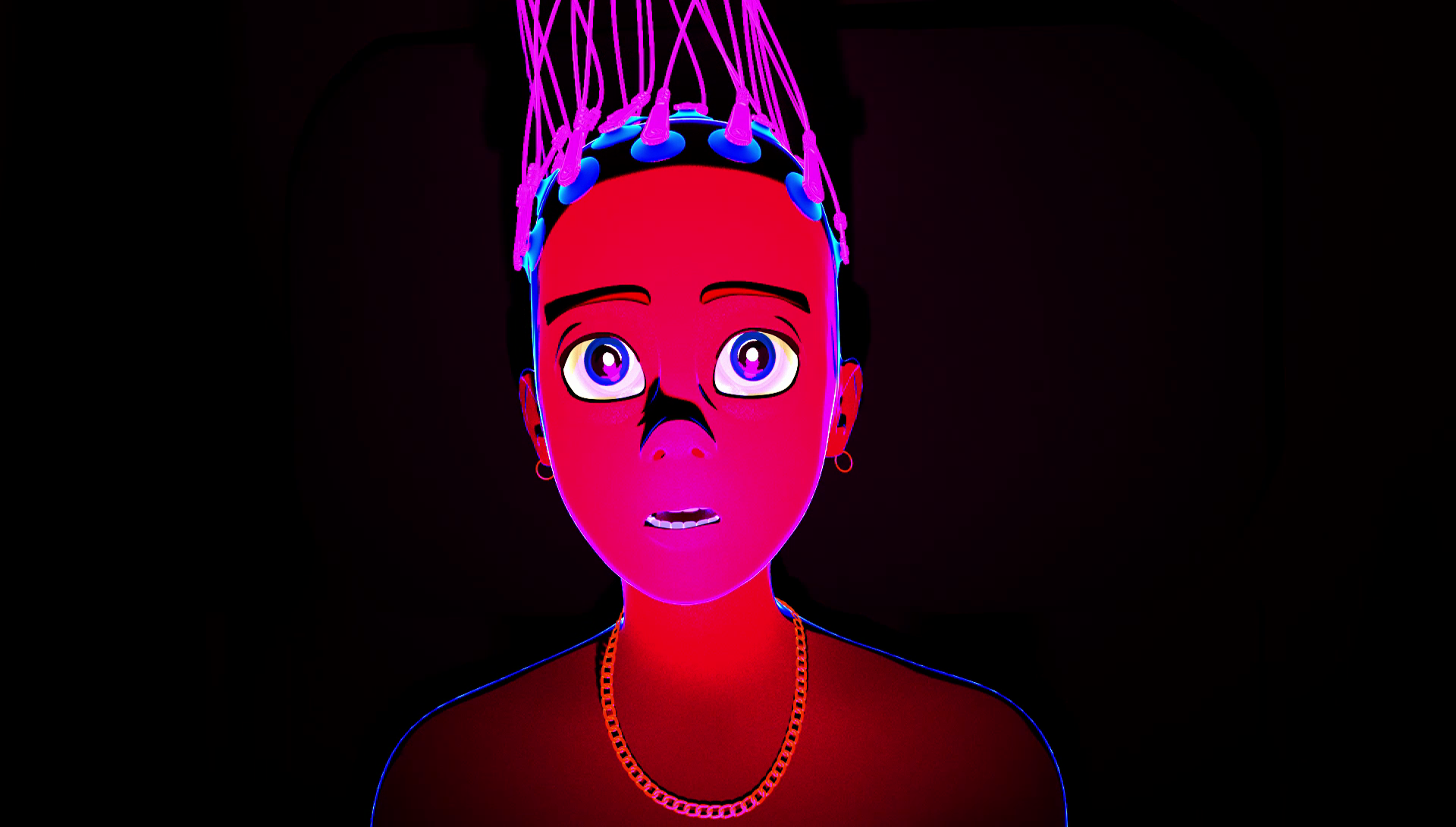

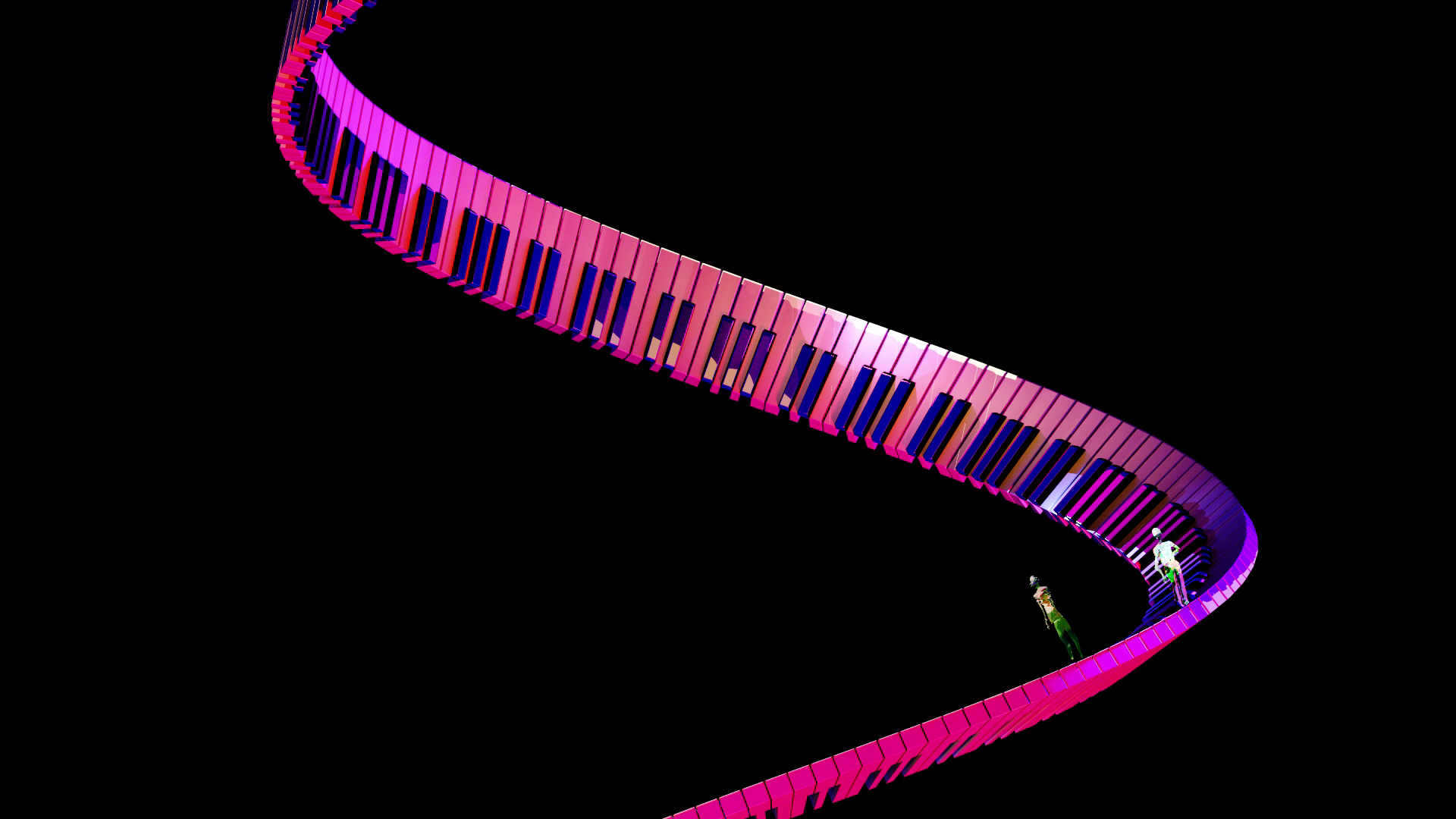

CULTURESPORT represents the fourth seismic career change for Internet artist John Michael Boling, previously known for his work as a music video director, associate editor at Rhizome, and co-founder of the social network are.na. A 3-D animation studio operating entirely on the open source software Blender, CULTURESPORT has been making waves with their highly recognizable commercial work for Telfar, Supreme, and Kenzo, while building a cult following on Instagram. This has all been in anticipation of a mysterious pilot episode, which has finally been released for free in support of their seriously extra Kickstarter (spoiler alert – the campaign was a success). “Rotterdam 1995” – the first installment of a transhistorical series about the genesis of a chatbot that leads an army of teenagers to take over the world – took five years to make, but was well worth the wait. To find out more about CULTURESPORT, the artist Cory Arcangel spoke with Boling about Internet videos, weaponized memes, and the power of parameters.

———

ASHER PENN: Could describe or define what CULTURESPORT is?

JOHN MICHAEL BOLING: I originally came up was that word combination when I was working at Rhizome. I can’t remember exactly, but I was doing a write-up for a blog post and I was thinking about Internet art and making stuff for the Internet, and what my relationship to that was. In thinking of what it means to make a thing and put it out in the world, I came up with this concept of CULTURESPORT. It’s basically like putting a media object into the world, but thinking about it like a sport. That was the departure point. We’re five years in now. We’re putting out this animated series, but we’ve also worked with arts organizations in the Netherlands. We’ve done music videos, we’ve worked on marketing campaigns and advertising campaigns. What can we say? How can we treat all these different layers of culture across mediums? How can we, with this project, play it like a game?

PENN: I was curious about how you guys first got to know each other, and how you’ve watched this genesis take place.

CORY ARCANGEL: The first incarnation that I knew John Michael from was from his web project, 53 os, which was a collaborative website. It had Internet art, that’s a complicated term, because sometimes it doesn’t feel like art. It’s like sometimes it’s kind of fun.

BOLING: At the beginning it was anonymous. I started it in response to my being disenchanted with art school and the art world, and I did it for fun. I thought if anybody ever ends up typing 53 os into Google, in their pajamas with microwaved lasagna, they’ll find this and it will really blow their minds. That was my highest hope for it at that time.

ARCHANGEL: I saw it originally through Delicious, which was a social network where people would share links to things they were interested in. You could easily find other people who are interested in the same things as you. At the time, the Internet was more open, and most everything resolved to a unique URL.

BOLING: It was a special time for the Internet, because Web 2.0 just kind of happened. Myspace was still bigger than Facebook. Tumblr didn’t exist. Twitter was maybe just starting to be an SMS service for bike messengers. This would’ve been 2000. The main 53 os stuff was from 2005 to 2008. I stopped making stuff when I switched to Rhizome full-time. I didn’t want to be some sort of gatekeeper. I wanted to make a clear distinction between making stuff and supporting stuff. I think I got a little nervous, because when I first started making stuff for 53 os, it was really fun. It was really free form. And then, when it got attention, and I was starting to get offers to be in shows and getting press and having people contextualize it as fine art, it kind of gummed up my creative engine. It started to feel a little alien to me.

CULTURESPORT

ARCANGEL: Can you talk about “Four Weddings and a Funeral”? That was the thing on 53 os that blew my mind apart.

BOLING: YouTube had just come out. YouTube, for me, is one of the biggest social keyframes from that decade. This new psychological landscape where everybody is now. Everything was on there and you immediately have access to it. It went from, you could only see the most amazing thing you’ve ever seen once a year, to seeing it 10 times a day. “Four Weddings and a Funeral” was in a series of YouTube collages. Visualize an HTML page, and on the top were four embeds of YouTube videos of weddings people had uploaded, and right below that was one video of a funeral. The idea was that, as people take these videos of weddings down, I’ll be able to replace them. The HTML follows instructions for a piece that could be recreated 20 or 30 years from now. I remember it feeling really weird at the time that somebody had uploaded a funeral to YouTube. It doesn’t feel weird anymore. I think that with the art from that time, there’s no way you could put it in a gallery. It’s not the same. The experience is totally different.

ARCANGEL: It was a joke work, but it was also meaningful. It was right at the edge of what was possible. I remember thinking that this is what art should be now. After Rhizome, you do something like completely different, which is you basically start your own social network.

BOLING: 53 os was me and Javier Morales, who consequently has the world’s best Instagram and YouTube account to this day. Are.na was after.

ARCANGEL: Do you wake up one day like, ‘I need to start a social network with my friends?’

BOLING: I started it because Yahoo bought Delicious and fucked it up like they do with everything they buy. I felt a real hole in my heart and soul for what Delicious was and what it could do. I felt a real need to replace it. I came across the word Are.na, and the domain was available, which was amazing to me. A-R-E-dot-N-A. That period of interacting with Are.na, collecting reference and interacting with the community was pretty key to a lot of the stuff that worked its way into CULTURESPORT. It was like a really intense research and reference, but without knowing where I was going to go.

CULTURESPORT

ARCANGEL: How long did it take you to understand that you wanted to do an animated series?

BOLING: It was six months of pretty much non-stop, in the studio, learning Blender. When I left Are.na I had just enough money saved up, so I knew I had six or seven months where it’s all I had to do. I wanted to get back to my original dream, which was to make movies and TV. There was this one that I kept coming back to, which was “Best Friends Forever,” which is a story about a chatbot that becomes self aware and recruits an army of teenagers to take over the world. It was originally supposed to be live action, but it was going to be expensive to do. I starting to make concept art for it in Blender, and at the same time through Are.na, I had been put into contact with a lot of really good anime. I was thinking about the story, and then I thought, well, what if I could make this? Anime is this beautiful form, and it’s totally economical. I spent a month working on what was the original formula for CULTURESPORT, and by the end of the month, I thought, “This is it. I can do this.” But I couldn’t do it in New York, because it’s too expensive. I talked to my brother, and he and I had been wanting to work on a project together for a while. I told him if he wanted to put a few thousand dollars into the production, then I’ll move down to the family farm for three months and come back with a pilot. He was down to do it. A week-and-a-half later, I had my birthday party at my apartment and told everybody that I was going to Georgia. I set up the first office for CULTURESPORT in this general store, which had no Internet, and went to the task of building up the world, coming up with the story, and figuring out the characters. A lot of the way we do CULTURESPORT is with duct tape maneuvers that I would figure out because I couldn’t get the real answer. A lot of the references for the characters in this world were based on what was at hand in the general store, which was my 500 or 600 VHS tape collection from when I was in middle and elementary school. If I needed to have a reference image for a city street, I would put on Coming to America and I would pause it. There was also a really cool volume of the Encyclopedia Britannica, so that was my Wikipedia. That’s one of the things that was really cool about that phase, having to figure out how to do things because I couldn’t Google it.

ARCANGEL: It really shows in the first episode. It’s impossible to understand the era. The references in the episodes were kind of ad-hoc – they didn’t seem like they were coming from the Internet.

BOLING: Limitations are so powerful. That’s one of the things I worry about, the fact that we’re not at the farm anymore. Being there, my Internet habits totally changed. The first few weeks was really strange. Then myself, Joe Kubler and Jason Coombs, who are principle 3D artists on CULTURESPORT, we moved to Athens because it was too cold in the general store. I had a kerosene heater next to a computer to try to warm us up.

ARCANGEL: I feel like your friends were a little worried about you at this point.

BOLING: They definitely should’ve been. The thing I like a lot about the Rotterdam episode is that took all the building blocks of the CULTURESPORT universe and imposed another limitation, which was being in the Netherlands in 1995. I didn’t know anything about the Netherlands before this project.

ARCANGEL: Why the Netherlands?

BOLING: There’s a pretty cool arts organization in Rotterdam called Showroom Mama that emerged in the ’90s out of street art, and they did some really good net art shows too. The curator there, Marloes de Vries, reached out, and they wanted to do an exhibition. At this point, I was still loathe to place CULTURESPORT in a fine art context, but it’s the Netherlands, and they support art there. They said, “We can give you a grant, and then you can work for a few months.” So if we know they’re going to pay for three or four months of studio time, let’s do a site-specific episode instead of doing an installation in the gallery. We’ll use Rotterdam as a sort of limitation or reference for a storyline in a CULTURESPORT universe. CULTURESPORT is very music-driven at its heart. So I was Googling Rotterdam, and found out that hardcore techno kind of came out of Rotterdam in the early ’90s. And that was it, there we go. We’ll make an episode in the Gabber scene in 1995. Then I just thought, where is my bad guy? Where does he go in 1995, how do I get him to the Netherlands? What kind of like black magic computer science would be up to? The technological and cultural landscape of CULTURESPORT allows us to have an alternate technological pathway for developments. Storylines that happen in 2006 can be more futuristic in different ways than our experience of 2006 was in this reality. So much changed so quickly. That period from 2005 to 2012, things were done that cannot be undone, technologically speaking.

CULTURESPORT

ARCANGEL: I think that young people have this really incredible sense for the social world online.

BOLING: So much has changed that it’s impossible to even categorize it all. I think people today socialize differently – like communicating with memes. I think the best work being made right now are memes. It’s like watching really quickly weaponized neuro-linguistic viruses. Communications can happen immediately and deeply through an image macro in a way that could never happen before. The meme culture gives me hope.

PENN: Do you consider CULTURESPORT to be an artwork, or do you consider it to be the latest foray of a highly creative person?

ARCANGEL: Something is an artwork if enough people think it’s an artwork. Art can be a game. What I like about the first episode of CULTURESPORT, the Rotterdam ’95, is when I saw it on YouTube, I could imagine what it’s like to wander onto it. That’s the most mind-bending aspect of CULTURESPORT. It’s like you’ve wandered onto some lost television show. For me, it’s important to maintain an identity as a fine artist, because I like the game of art. I like making things and trying to convince people that they’re art. John Michael, what’s your preferred context for CULTURESPORT?

BOLING: I don’t know if I’ve figured it out yet. I would say with CULTURESPORT, time will tell. It’s going to be a sort of a sum of all its parts, wherever it goes. I’d see that question in five years, and then maybe I’ll have an answer.

ARCANGEL: If the Internet even exists in five years.

BOLING: The Internet will be our blood in five years.

ARCANGEL: The world will be on fire in five years.

———