Ann Patchett

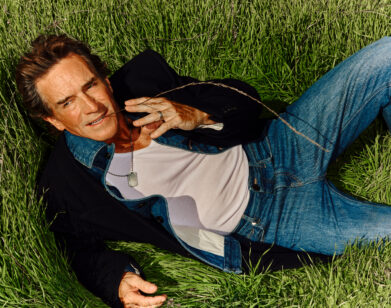

ABOVE: ANN PATCHETT. PHOTO COURTESY OF HEIDI ROSS.

“This is a story about the long-term outcomes of a seemingly harmless action—a drunken kiss at a party—on a large group of people,” says Ann Patchett about her compelling new novel Commonwealth (Harper). The narrative starts in Los Angeles in the 1960s with a backyard party to celebrate the christening of Franny Keating, daughter of Fix, a police officer. Mingling among the cops with their guns holstered is Bert Cousins, a womanizing D.A. who has shown up uninvited. He’s immediately captivated by Fix’s statuesque and slightly inebriated wife, Beverly.

Out today, Patchett’s Commonwealth is an intimate study of families, mistakes, redemption and more. Within just a few pages, Patchett establishes the drama and conflict that fuels this sprawling story across the breadth of the States and beyond. Now in her early 50s and based in Nashville, Patchett is a graduate of Sarah Lawrence College and the Iowa Writers’ Workship. She has written six previous novels and won numerous awards, including the Orange Prize and the PEN/Faulkner Award for 2001’s Bel Canto. Four years ago, she was named as one of Time magazine’s “Most Influential People.”

JEFF VASISHTA: There are many fascinating characters and relationships in the novel. I found the Franny/Leo Posen romance particularly interesting. I was reading it, thinking you had the inside scoop on lonely male writers at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

ANN PATCHETT: I had the inside scoop on lonely male writers at the Iowa Writers Workshop, but more importantly, I have the scoop on lonely men, or maybe lonely older men, or maybe just men, or maybe people. Yes, let’s go with people: some people need a huge amount of attention, and they are worthy of that attention, and they’re still exhausting. Surgeons come to mind. In my experience surgeons tend to need boatloads of attention. All by way of saying a person doesn’t need to go to Iowa and sit through the readings of incredibly brilliant, charming, needy, drunk, famous writers in order to write about them.

VASISHTA: Was Fix in any way modeled on your own father?

PATCHETT: Sure. My father was a police officer in Los Angeles. He had a beautiful wife and two daughters. Fix isn’t my dad—they have very different personalities—but I borrowed many facts from my father’s life in order to make the character. I’d never done anything like that before and I wanted to see what it was like.

VASISHTA: Bert is someone I found myself wanting to strangle for his lack of responsibility. But with all the parents, perhaps with the exception of Fix, there is this feeling of just how hard parenting is—if you drop your guard for a second disaster can happen.

PATCHETT: Fix looks like the superior parent in this book because he doesn’t raise his children. I keep wanting to remind people that this was the parenting of the ’60s and ’70s. It really was a different time. I knew lots and lots of fathers like Bert when I was growing up. They didn’t give their children much thought. That seemed to be the social norm.

VASISHTA: I couldn’t help but feel Beverly really made life difficult for herself for no good reason.

PATCHETT: I wish we could go out to dinner and talk about this question for three hours: “Beverly really made life difficult for herself for no good reason.” Isn’t that what people do? I’m sitting here making a mental list of people I know and many of them made their lives difficult for no good reason. It’s the human condition. There are, of course, people who didn’t create the trouble they’re in, but lots of them do.

VASISHTA: Many of these characters—Albie, Cal—seem to be on a pre-destined path for destruction. Did you craft them with their outcomes in mind from the beginning?

PATCHETT: I craft everything in the beginning. I know where the characters are going before I start writing the book. I think things turned out to be hardest on Albie because he was the youngest and no one had the time or energy to provide him with a childhood, no one wanted him around. Things turned out to be hard on Cal just because of fate, bad luck.

VASISHTA: The danger of guns looms over this novel both with Cal and later Fix.

PATCHETT: Guns are dangerous and damaging even when no one gets shot. They really do loom.

VASISHTA: Albie is fascinating because of the redemptive aspect to his life. Did you initially intend for him to be such a central character?

PATCHETT: I did. Right after I published State of Wonder I was on a train going from London to Wales with my British publicist, a woman named Katie Bond. She was telling me about her little son Albie and he just sounded like the most fascinating kid. I thought, I want to write a book about a boy named Albie. That really was the place this book started from.

VASISHTA: It’s interesting that you set a novel within a novel, and that Leo’s book is also called Commonwealth. What made you decide to give them the same name?

PATCHETT: It’s essentially taking a fat black marker and drawing a line under the title of the book. Leo and I are both writing the same book in a sense.

VASISHTA: Were you concerned about creating an intimacy with such a large cast of characters?

PATCHETT: No, I love a large cast of characters. That’s the way life is: it’s flooded with people and we keep them all straight. We have different kinds of intimacy with many, many people. I’m disappointed by well-written novels that only deal with two or three people.

VASISHTA: You suddenly have a flashback in the middle of a scene, but we are not made aware it’s a flashback, which can be a little disorientating at first. Why did you use that technique?

PATCHETT: It wasn’t a choice. The problem is when you’re the one writing the story everything seems perfectly clear, so those flashbacks seemed clear to me given the circumstances the characters were in at the moment. I think that’s the way the mind works: the moment we are in throws us back to another moment of life without any warning.

VASISHTA: I loved the scene where Franny frees the lobsters. Where did that come from? A secret wish?

PATCHETT: I’m very sentimental about lobsters. The last lobster I ate was the only lobster I cooked. The David Wallace essay “Consider the Lobster” also plays into it. Franny is having a tough time in that chapter in the Hamptons. She relates to those lobsters alone in their boxes and so she does something about it. She saves their lives, and when she comes back, Albie shows up and saves her.

VASISHTA: Holly says at one point, “We were such a fierce little tribe.” This novel shows how kids in blended families can form lasting friendships even when, or especially when, there’s a degree of dysfunction with the parents. Did the inspiration come from just people watching over the years?

PATCHETT: It came from people watching of an up close and personal nature: I have seven step-siblings from my mother’s second and third marriages. My degree of closeness to my step-siblings varies among the seven but I have a great sense of loyalty to all of them, especially the four from my childhood. If those people needed my help I would be there for them.

VASISHTA: How, if at all, has you writing process changed over the years? Do you have a notebook where you write down novel ideas? How do you decide that the kernel of an idea could be turned into something bigger?

PATCHETT: My writing process has changed because it’s harder to find uninterrupted time. I can feel very sentimental about my life before email. I tend to keep my ideas in my head. When I write something down in a notebook it’s never centralized. There are too many notebooks floating around, but maybe that’s a good thing. The idea I pursue is the one that keeps coming back to me. The characters I think about as I’m falling asleep at night or when I’m driving to the grocery store are the one’s I wind up writing about.

COMMONWEALTH IS OUT TODAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 2016.