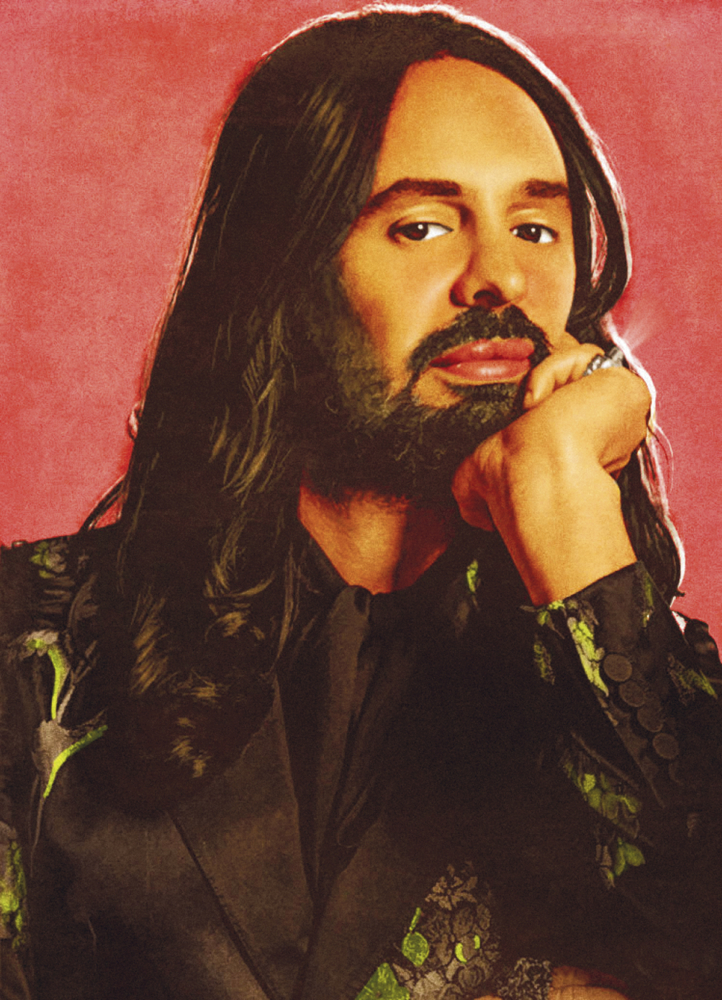

Gucci’s Alessandro Michele on Authenticity in the Age of Artifice

Well, technically it’s a photograph e-mailed to us by the Gucci communications office, taken by the photographers Inez & Vinoodh, altered by a retouching artist named Justin Metz to look like an Interview cover from 1981 of the legendary musician Diana Ross, created by the artist Richard Bernstein — but who’s counting?

Augmented reality. Fake news. Alternative facts. It’s a troubling time for seekers of authenticity. Gucci’s creative director, Alessandro Michele, knows this better than most. Since reinvigorating the luxury fashion house when he came on board in 2015, the 46-year-old Italian designer has been working through ideas about dovetailing originality and appropriation. Take, as evidence, Gucci’s recent partnerships with Trevor Andrew, an ex-Olympic snowboarder whose graffiti alter ego, GucciGhost, led to a handbag collaboration; and Dapper Dan, the Harlem-based designer whose Louis Vuitton “knock-up” jacket was copied by Michele into a jacket of his own, which then ended in an unlikely arrangement whereby Dan was invited to design a capsule collection for the house. Confused yet?

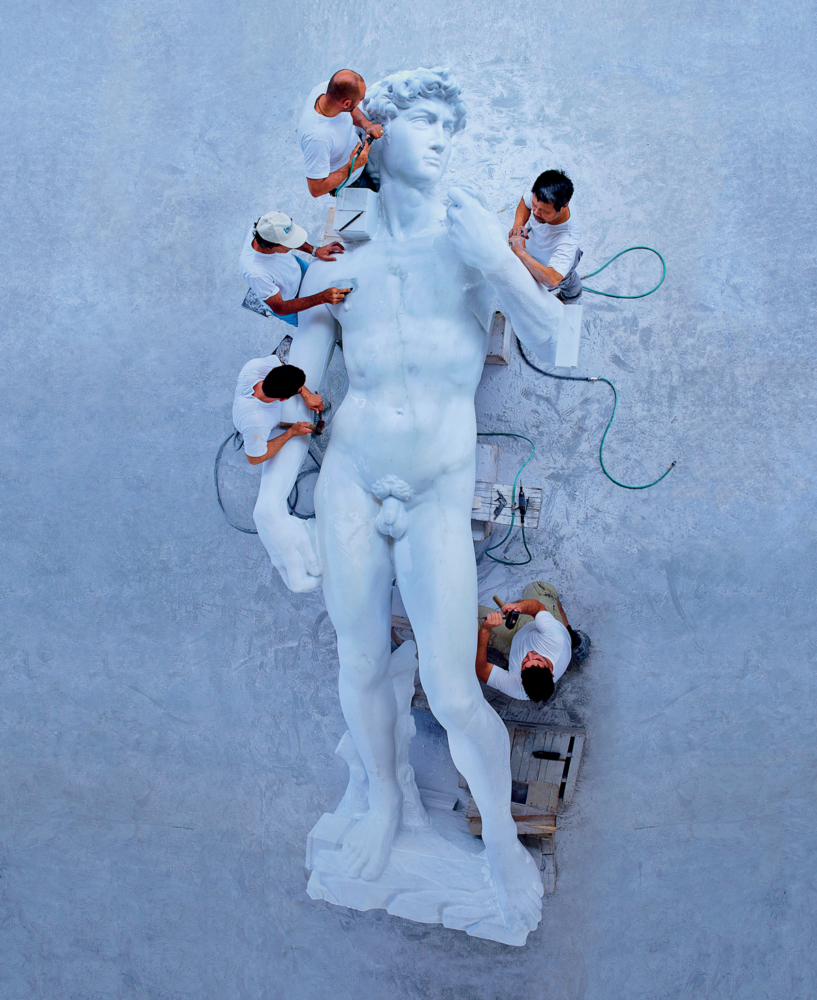

Imagine how I felt when, on a windy October afternoon, I arrived at the Yuz Museum, in Shanghai, to find giant posters promoting the opening of an exhibition called The Artist Is Present—the name of the wildly contentious 2010 performance piece by Marina Abramović that lasted 700 hours at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The title of the exhibition aside, the image of a brunette woman on the poster bore an uncanny—but not exact—likeness to Abramović, strange given that Michele and the art-world provocateur Maurizio Cattelan were co-mounting this new show, and that the Serbian artist was, in fact, absent. Inside the gallery, workers in plastic protective booties were putting the finishing touches on a hallway suffused with pink-and-blue light that felt downright Turrellian but was actually created by the artist Kapwani Kiwanga. There was a machine that simulates the human digestive system by Wim Delvoye and self-portraits of Gillian Wearing as her parents. There was even a replica of the Sistine Chapel, one-sixth the size of the original, by Cattelan himself. When my tour was over, I flagged a car to Michele’s hotel to learn more about the power of plagiarism.

———

NICK HARAMIS: What is it about the idea of a copy that interests you?

ALESSANDRO MICHELE: Art is about connection. No real artist wants to make a piece and close it in a box so that nobody gets to touch it. In the same way, fashion is about connection. It’s no longer enough to make chic clothes and put them in a boutique. Fashion is supposed to be alive. It comes from the streets, from music, from the club. But to answer your question: This old lady called “fashion” was dying, so designers decided they needed to make the bag of the day. They’d take a piece of art and put it on a bag for no reason. It was just a trick to get people buying.

HARAMIS: Yet the overall thesis of this show seems to be that there is creative potential in plagiarism. What’s the difference between an inventive reproduction and a counterfeit?

MICHELE: One creates a conversation and isn’t really copying. It would be like saying Mozart copied his compositions because he used musical notes. If I need something to tell my story, I can’t be shy. I don’t care how it comes across, because everything is my truth. I don’t replicate something in my work because I need the replica. I do it because I need the note. Mickey Mouse is a note. Dapper Dan is another note. But a copy for copy’s sake, just to sell a pair of shoes, is really sad. They’ve lost the chance to do something personal, and instead they’ve just made a product.

HARAMIS: How do you feel when people copy you?

MICHELE: I don’t care. And not like, “Oh, I don’t care—I hate them.” On the other hand, when I look at the people who try to copy me just to create confusion about what’s real and what’s fake, I think it’s a shame because, in a way, it’s like they’re destroying my work. If you try to make the same thing without a soul, it will be trashy and ugly. I’m always trying in a very delicate way to put together things that are dirty with things that are completely clean, things from the bourgeois and things that belong to the ghetto, things that are completely broken with things that are well done. I love when people on Instagram try to find the seed of what I’m doing—even if they’re not always right, they’re often close.

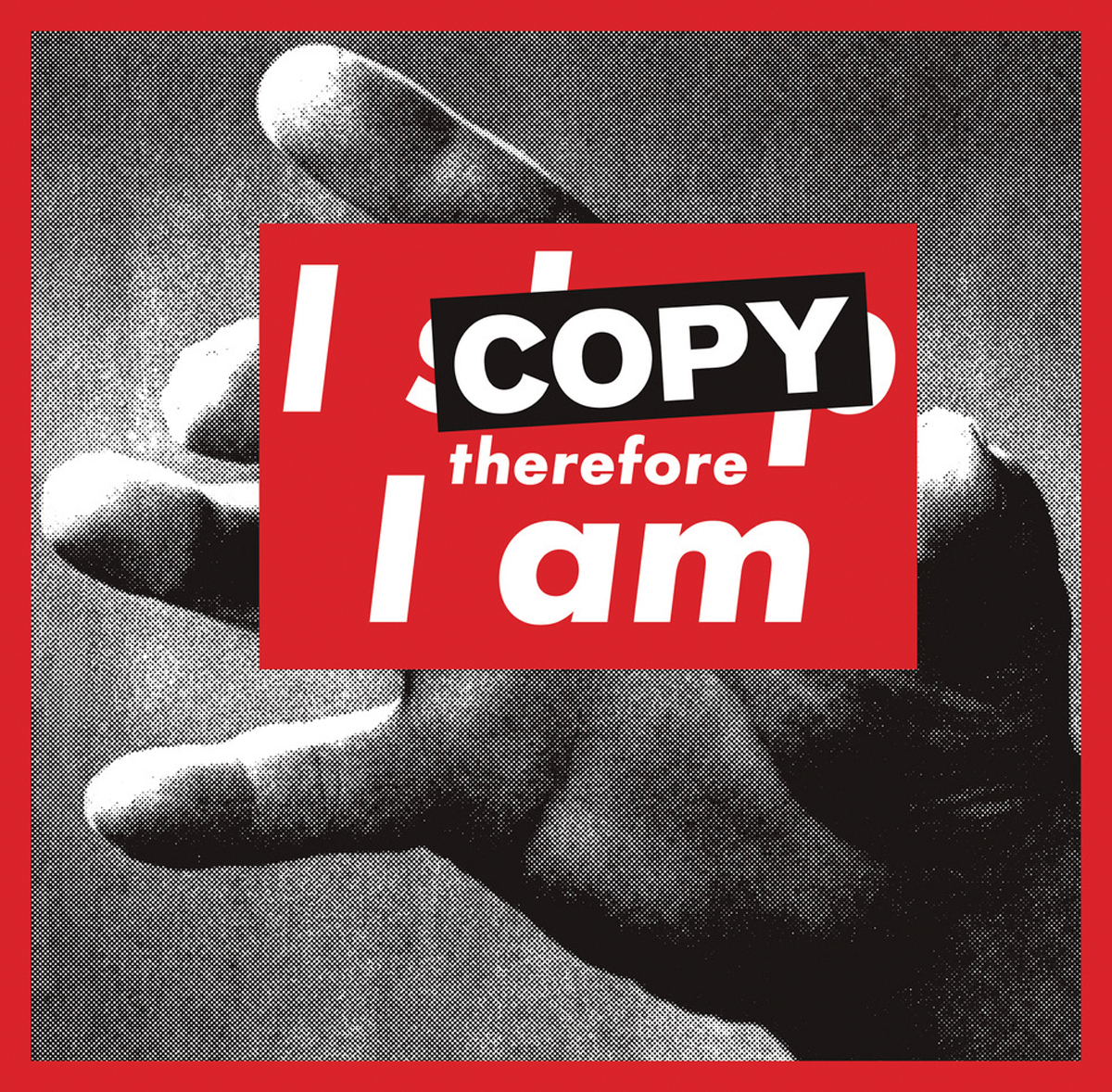

“SUPERFLEX, I COPY Therefore I am,” 2009. Photograph courtesy of the artists / The New Work Times.

HARAMIS: You’re talking about your references for a collection?

MICHELE: The Instagram account Diet Prada will sometimes find references in the clothing that I didn’t even think about, which is great because it provides another point of view.

HARAMIS: You’re clearly a lover of vintage clothes. In a way, when I look at your collections I feel like I’ve stepped into the most creative vintage shop.

MICHELE: That’s why I always say that the last look in any given collection is not really the last one—it was just that I didn’t have more time. I never say that I made a collection because I think this is what the season is like—it’s not true. I’ve just been playing for months. These are the things that came to me in five months, and this is a piece of my perversion during that time. I think that we need to work a little bit more with our guts rather than just stand in front of a color palette.

HARAMIS: Do you always have a well of inspiration you can dependably draw upon?

MICHELE: It’s really just my life—my apartment, or my storage unit where I keep things I’ve forgotten I even had. Sometimes I go there just to find something new. I was thinking about the idea of the theater when I was working with my team on the Spring 2019 show, and we ended up making some really bourgeois dresses and jackets. So when I added Mickey Mouse in the mix, everyone was saying, “It’s too crazy. It looks like you went to The Disney Store.” But that’s where I thrive—in my creepy subconscious. This is the secret place. It’s important to me that I just try to put it all on the table. It’s like being in front of people and saying, “Okay, I don’t care. I’m going to take off my underwear.” What does inspiration mean, anyway? Nothing. How can it be just one thing? In a moment you can feel like one person, and an hour later you’re someone else. I was painting my nails the other day—

HARAMIS: [Pointing at Michele’s nails] I can see that. But why just two of them?

MICHELE: Let me tell you a funny story. When I was a little guy, I was always playing with my mom’s nail polish. I was in love with the little bottle and I loved color. When I was trying to choose the right color for the models in the last show, I said, “Red is beautiful because it was the color that my mom usually wore. And it’s so punk.” But because I was choosing from a lot of options, I only had two nails left to paint at that point. And then I noticed how cute it was that I have these really massive hands with two nails painted red. It made me feel so happy and chic because it’s so wrong. I don’t think I did a very good job, though. I’m getting older, and I can’t see if I don’t have my glasses.

HARAMIS: Well, I think you did a great job.

MICHELE: Not really! I went to art school, and I was really good at painting. I blame it on the brush. Anyway, it’s funny watching people watching me. I can tell you’re sort of hypnotized.

A crew working on a reproduction of Michelangelo’s David in Carrara, Italy, 2006. Photograph by Maurizio Cattelan and Pierpaolo Ferrari / The New York Times.

HARAMIS: I mean, there’s a lot to look at, Alessandro.

MICHELE: [Laughs] There is a lot. My rings are something that I love. I don’t know why. Maybe it’s my way to feel young, to preserve the voice of the kid inside me. To keep that alive.

HARAMIS: In some ways, that youthful spirit is comparable to the outlandish and liberating sensibility of camp. News came out today that you and Lady Gaga will be among the host’s for this year’s Met Gala, which is centered on the idea of camp.

MICHELE: Embracing camp is like having a conversation with a part of you that’s normally kept hidden. I feel like I’m always fighting with a lot of Alessandros inside me. These crazy conversations help me feel alive, which is important, otherwise I’d just be a fashion designer. That would be like putting myself in a tomb. It would be like saying I am just the boyfriend of someone else…that’s it. I’ve been with my boyfriend from almost 11 years, and people keep saying, “You need to get married to him.” I’m always thinking, “But why? I want to feel free to break up tomorrow.” It’s also the way I feel about working for Gucci. I don’t care if tomorrow will be the last day, and that’s freeing. Otherwise I’d just be working to keep the position, which inevitably is not sincere.

Guy Isnard, one of the first policemen to specialize in the forgery of artworks, preparing an exhibition of Mona Lisa falsifications presented in the Grand Palais of Paris in 1955. Photograph available on Pinterest.

HARAMIS: Does that mean you don’t put a lot of pressure on yourself each time you make a new collection?

MICHELE: I never feel the need to say something new. It’s new just by the way I say it. It’s new because it occurs in the right moment. If I read a poem in front of you now, even a really old one, it would be new for us even though it’s not.

HARAMIS: I’ve heard you say that you don’t care about the future.

MICHELE: I don’t. I mean, come on. I’m not god. You could think that I’m the coolest and most attractive fashion designer, but I’m not unique. I’m only unique because I’m me. Just like you are only unique because you’re you. I’m not a diva.

HARAMIS: Given that, when you first entered into the world of fashion, did you feel totally at home?

MICHELE: No. But I feel at home now, because I’ve known the people I work with for a very long time. I feel at home in this company because there’s such good energy here and because they’ve given me the power to say something. The first time I went to the Met Gala, I thought, “This is just a group of human beings—just like me, just like everybody.” I’m never going to be the kind of guy who’s always in Saint-Tropez. No matter what, I feel like such a little villager.

Maurizio Cattelan, “Untitled,” 2018. Photograph courtesy of Gucci.

HARAMIS: You were born in Rome. What were you like as a kid?

MICHELE: I was really eccentric. I changed the color of my hair when I was 11.

HARAMIS: To what?

MICHELE: This really bad blonde.

HARAMIS: I frosted my tips, because of that damn Pacey Witter on Dawson’s Creek.

MICHELE: I locked myself in the restroom, and when I came out, my dad said, “You look so bad.” I grew up in an area that wasn’t exactly the most appropriate place for a guy like me. I fought a lot to be who I was, and who I am now. The way I looked was an affirmation of my identity. My hair, my shoes, my pants—each part was like a war. Every day. I was kind of a masculine, sporty guy, but there was always something feminine in me. I was in love with dark music, and I felt like kind of a rock star. I remember when I came out to all my heterosexual friends, I said, “I think that I’m in love with a guy.” I was so unprepared to have that conversation, but even as a kid I’ve tried to be sincere with the people around me. It’s the same to this day. I’m still fighting with myself, with all the things in me and with all the things that surround me. I want to disturb people, but in a nice way.