Toyin Odutola and the Public Struggle

Last week, 28-year-old artist Toyin Odutola was home for Thanksgiving, back in her childhood bedroom, where, as she recently posted on Instagram, “My past efforts haunt me. Ha!” Odutola isn’t afraid to blog about her failures, successes, and everything in between; indeed, she says that her work is all about process. Now, 13 of her arresting pen-and-ink portraits, which caught the art world’s attention after a sold-out show in Chelsea last spring, are the focus of Odutola’s first solo museum exhibition, “The Constant Struggle,” opening at the Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art on December 6.

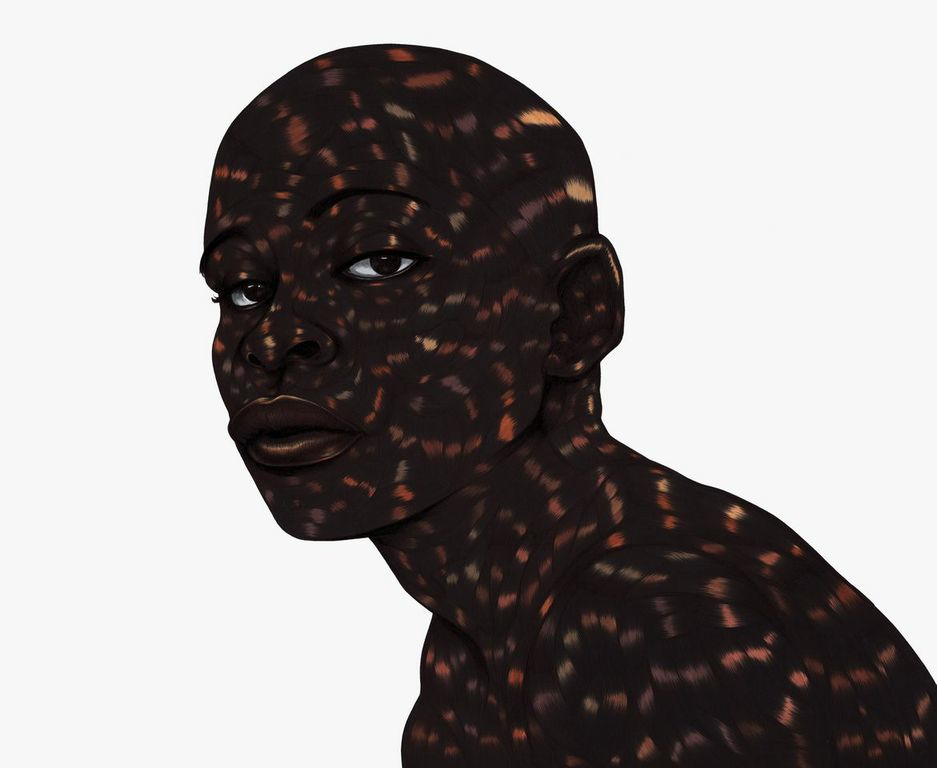

Born in Nigeria, raised in Alabama, and trained at the Bay Area’s California College of the Arts, Odutola draws on references as diverse as her upbringing, from animated Japanese serials and African carvings to the sinews of anatomical diagrams. But the blank white backgrounds on which she’ll place a disembodied arm or head, the subject’s dark skin radiating with flashes of disco-colored strobe light, strip away any context, preventing viewers from creating narratives about who’s pictured. Instead, with their open expressions, these figures look back at us, shifting power away from the audience by reflecting our own gaze, and calling into question ideas of identity and race.

At Art Basel Miami Beach this week, Jack Shainman Gallery presents Odutola’s most ambitious work to date, a five-foot tall portrait from her latest series, while earlier pieces are currently on view in group shows at Brooklyn’s Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts (MoCADA) and the Jenkins Johnson Gallery in San Francisco. Effusive, gracious—and quick to slip on an accent (Southern or Nigerian, depending on the story)—Odutola spoke over the holiday weekend about what’s ahead and knowing when to let go of the past.

JULIE BRAMOWITZ: You recently relocated to New York. What has that been like as an artist, and do you find it distracting to work in a city with so much stimulation?

TOYIN ODUTOLA: It’s been six months, and I’m not going to lie: It is hard to produce work in New York. You kind of have to center yourself—do some Zen meditation exercises and just focus. [laughs] It is very distracting, and money, of course, is an issue. I don’t think I would have been able to make the work that I made for the show in May if it wasn’t for me being in Alabama and away from New York, because it does have this way of influencing how you feel about your work. You hear outside voices and it permeates all that you do. But so much has happened for me in the studio here and I know that direct contact with inspiration wouldn’t have happened if I didn’t have access to what you have in New York, such as galleries, museums, lectures—what I could only access through the Internet in Alabama. I remember just recently going to the Edward Hopper show at the Whitney. Of course you read about his work in books, but to actually be in a room where you can study his hand, his mark, it changes your entire education.

BRAMOWITZ: You’ve mentioned Hank Willis Thomas as a mentor. Could you talk a bit about his influence on you as an emerging artist?

ODUTOLA: Oh, yeah. Hank says that I mention him too much, and I need to quit because people are starting to feel a certain way. So there’s this joke between us that the next interview I do, I say, “I don’t know who Hank Willis Thomas is. I met him one time and it was really awkward.” [laughs] Hank’s great. He’s the one who “discovered” my work and saw something that I didn’t see. He’s still constantly pushing me to try out new ideas and not be afraid of what other people will say. He truly is a mentor, and I often ask him about the art world, how to juggle it all and not lose your mind. It would be like accepting an award without thanking him because he really has been so supportive.

BRAMOWITZ: Since joining Jack Shainman Gallery, are there other artists whom you’ve had an opportunity to meet and whose work has informed what you’re doing?

ODUTOLA: Jack’s gallery is great, because there’s a lot of people whose work I admire and I didn’t even know were represented by him until I got there and was like, “Oh, shit!” I’ve had the chance to meet people that I think are icons, like Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and Kerry James Marshall. Kerry James Marshall especially was a huge influence on me in graduate school, as were Wangechi Mutu and Julie Mehretu. These artists are titans. My education was also very much in comic books, so I’ve been going to comic book events in New York and have met a few artists there.

BRAMOWITZ: Anyone in particular?

ODUTOLA: Cathy G. Johnson, who does a lot of web comics. I love her style. It’s very different from mine, so I don’t know if people will see the connection, but I’ve definitely played with some things just looking at her work. Anthony Cudahy. Mostly indie artists that I’ve been following for a few years online. I’m really interested in independent publishers and memes and mini comics. But even before that, I was interested in Japanese manga and anime.

BRAMOWITZ: When you’re creating a series, do you conceive of it like a graphic novel, in which there’s a narrative and images are ordered as a sequence of events?

ODUTOLA: I think about composition and narrative a lot. Each piece, in a way, is a panel. It’s easier to tackle it when you think about the silhouette in that contained space. The graphic style itself is influenced by a lot of very layered and detailed comics that I read as a kid, like Vagabond by Takehiko Inoue. Sometimes I’ll do sequences or multi-panels where there’s movement, kind of like a movie.

BRAMOWITZ: What’s the story behind your latest series, “Of Another Kind”?

ODUTOLA: It came from a postcard that I bought at some museum store. It was a sculpture of a young boy in gilded bronze. His skin was black, and his hair was this shocking blond. His hands were above his head holding out a cigarette tray, and he was standing on top of this leafy gold setting. It was very strange and I didn’t understand why I liked it. I hated the servitude aspect, that it was just for someone to put down their cigarette. But, as an aesthetic, I loved the black-and-gold combination repeated throughout. So I started researching references. The more examples I would find, the more I had to type in “Moorish sculpture” or “Moorish portraiture,” the mode for portraying “Moors”—basically, blacks—in Medieval and Renaissance Europe. I liked the aesthetic but I didn’t want to fetishize or perverse it, so that became a vehicle for me to explore it but without the subjects being exoticized or serving a purpose, like an ashtray. The title, “Of Another Kind,” is about looking at this genre from another perspective. The series also changed how I consider restriction when it comes to palette.

BRAMOWITZ: For the golden sections, what are you using?

ODUTOLA: It’s a Sharpie, girl! It’s a gold Sharpie from Office Depot. The whole piece is first done in pen and ink to engrave the surface of the paper, and then once that dries, the areas that I want to be gold I go over with a marker. That gives it the texture underneath, but also the sheen of gold on top. It’s important for me to emphasize texture, to get that sculptural feel, which is what influenced the entire series because I was largely looking at sculpture and reliefs.

BRAMOWITZ: You were born in Ife, Nigeria, which is known for its carved sculpture tradition. Did that play a role in your earlier work where you focused on faces and expressions?

ODUTOLA: Ironically, I didn’t know about the Ife sculptures until I came to America. It’s so funny that I would be doing this work that’s heavily drawn off of scarification, striated lines, that whole aesthetic. When I went back to Ife for the first time with my mom, we visited the museum there, and I was blown away. Up to that point, I thought that this style of mine was just this weird amalgamation of all these disparate references, and it made perfect sense once I saw those pieces. There are mirrors with my work, especially with the faces, the emphasis on the head, which, of course, is identity. You rarely see the whole body, and it’s usually dwarfed by the face. But it was absolutely something that I came to later. My mom always says, “It’s like you’re coming home.”

BRAMOWITZ: I read in a previous interview that you’ve been wary of depicting women. What pushed you away from portraying female subjects and towards males?

ODUTOLA: For a while, I was nervous about portraying women because of the objectification that automatically comes with it, whether the artist intends or not. With “Of Another Kind,” I’ve not so much drawn nudes—I hate saying “nudes” because it’s not a spectacle—but portrayed people naked. I see them in a more straightforward way—exposed, but with no indication of who or what they are; they’re just there. That’s a very powerful statement because when they’re stripped bare of everything, there’s no marker for people to label them or place them in a box. I wanted to twist that, so I use my brothers a lot, portraying them naked, open, exposed. That’s something you don’t see a lot, especially with black males, unless it’s referencing slavery or pain.

BRAMOWITZ: The focal point of this series is a departure for you: Rather Than Look Back, She Chose To Look at You, a five-foot female portrait that will be on view in Miami this week. You worked on this piece over three years?

ODUTOLA: I started it and was like, “Mom, I don’t think I can finish this piece,” and she was like, “No, you’re not ready.” [laughs] So it was just stored away, and every once in a while I would bring it out and work a little bit on it, and then I’d put it away again. Then I decided to move to New York and was like, “I’m not going to finish this. It’s been in the basement and every time I come and work on it a little bit, it’s just more depressing to me.” But my mom kept saying, “Take it with you.” So I took it back with me, put it up, and said, “You know what? If there’s one thing I’m going to finish this year, it’ll be this piece.” I was sick of having it be incomplete and I just went H.A.M. on it. I spent a good four to five months working on it, along with other projects. Once I finished, the piece was really about me dealing with a past that I felt haunted by, about Ife, as well as about coming to terms with failure. Suddenly you find yourself in the present with a finished piece and going, “I’m done. I can’t keep feeling a certain way about the past.” That’s what the title is about.

BRAMOWITZ: When you post works in progress on Tumblr and Instagram, is it essential to your process to document these phases online and gauge the reactions of fans?

ODUTOLA: I originally started blogging because I didn’t know if I wanted to be an artist. I wanted to talk to other people online who were doing art, so I would post work and ask for feedback. I loved that an artist like James Jean would show his process on his blog. It became this open dialogue that, unfortunately, we don’t have a lot in the fine-art world. People will say, “Wow, you share a lot.” I’m like, “No, I make it a point to.” Instagram is a great place for people to share failure. I don’t want people to think that being an artist is some glamorous life. Not everybody is Jeff Koons. Not everybody wants to be Jeff Koons, you know? You go through a lot of battles in your studio. I’ll say, “I’m having a certain feeling about this piece and it’s not a good one.” [laughs] People respond to that in a very positive way. There are moments when they tend to get a little too fresh or try to art direct. But I’m just lucky to have someone see the work and be a part of the process in real time.

BRAMOWITZ: You’ve got several group shows lined up this coming year. What else can we expect in 2014?

ODUTOLA: I recently started working in charcoal and pastel. I hadn’t touched them since I was in high school or early college, but I had been working in pen and ink for so long that I was like, “Okay, I need to break free of this.” So I just picked up a charcoal pencil that I had around the studio and started drawing this piece, The Paradox of Education. I don’t know where it will go but I would say 2014 is going to be a year of different materials. The pen and ink was my hand’s education; now my hand is applying that same style with new tools.

RATHER THAN LOOK BACK, SHE CHOSE TO LOOK AT YOU WILL BE ON VIEW AT THE JACK SHAINMAN GALLERY AT ART BASEL MIAMI BEACH FROM THIS THURSDAY THROUGH SUNDAY, DECEMBER 5 THROUGH 8. “THE CONSTANT STRUGGLE: TOYIN ODUTOLA” OPENS AT THE INDIANA MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART THIS FRIDAY, DECEMBER 6. “SEVEN SISTERS” IS ON VIEW AT THE JENKINS JOHNSON GALLERY IN SAN FRANCISCO THROUGH DECEMBER 21. “SIX DRAUGHTSMEN” IS ON VIEW AT MOCADA THROUGH JANUARY 19.

For more of Interview’s coverage of Art Basel Miami Beach 2013, please click here.