More Than Life: Thomas Demand in Monaco

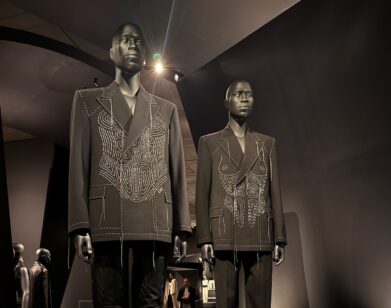

PHOTO BY LUIGI GHIRRI, CORTESY OF MONACO’S NATIONAL MUSEE NOUVEAU.

For the inaugural exhibition at its new Villa Paloma, the team at Monaco’s National Musée Nouveau bypassed professional curators, hiring German artist Thomas Demand to organize “La Carte d’Après Nature,” on view through February 22. Monaco itself is a freak of nature—or, rather, an example of industrial man conquering nature—with its pile of luxury high-rises hanging precariously on the cliffs over the Mediterranean sea at Monte Carlo. A millefeuille of green and concrete layers, it’s hard to tell where the indigenous ends and the plastic palm fronds begin. A lush stasis reigns over the principality, an eerie and confusing calm caused by the contrast of so many buildings and so few pedestrians, revealing Monaco’s status as a sparsely inhabited luxury kingdom. Who better than Demand, then, to curate a show here, which plays on man’s attempts to come to grips with the wild?

Monaco’s new National Museum includes a site dedicated to theatrical arts and currently features a show from Yinka Shonibare running through January 16. With its contemporary art museum under the direction of Marie-Claude Beaud, Monaco has opted for provocative and fun. Beaud is a French maverick that has continually straddled the borders between fine and applied arts most recently at Luxembourg’s Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, and previously at Paris’s Musée des Arts Decoratifs, the American Center in Paris and Fondation Cartier.

The whitewashed, multi-storied Villa Paloma, perched high above Monte Carlo, recalls the principality’s gentler, pre-high-rise era, and is the ideal size for a single show. Demand chose 17 artists, including Tacita Dean, Becky Beasley and Martin Boyce, for a show inspired by the René Magritte’s 1950s–’60s project of the same name that comprised a series of postcards mailed to a select group. And so it’s man’s view of nature that captures the attention of Demand and the other artists. “This show was quite an adventure,” said Demand. “There was very little time to prepare, no specific agenda and we hadn’t seen most of the 50 works in the flesh before the installation.”

The revelation in this show is Luigi Ghirri, the Italian photographer who was something of a photographer’s photographer, and was on the cusp of mainstream recognition at the time of his death in 1992. Beaud and NMNM’s head of development Cristiano Raimondi’s relationship with Paola Ghirri, the photographer’s widow, enabled Demand to include many images never previously shown. Ghirri began taking pictures in the 1970s, when he was 30, and in 1975 he was chosen Discovery of the Year by Time-Life. In 1982, he began photographing landscapes and urban views and was singled out as one of the most significant authors in 20th century photography. Ghirri’s shadowy photograph of a monkey at the zoo, which looks like a piece of story board for a King Kong film, his photos of crinkled tissue paper covered with stars, of a caged canary behind a wire fence, or of tourists tromping through a model of Mont Blanc, set the surreal man meets nature tone of this show.

“Everyone at least once in his life has drawn a tree for his mom,” says Demand. “I wanted to find what an 1865 photograph in Dresden (August Kotzsch’s studies of sinister-looking garden sheds) has in common with Henrik Hakansson’s sound installation of birdsong and morning traffic in Monaco.”

Demand concedes that Magritte is this show’s “elephant in the room,” as well as the hinge that connects Ghirri and all the other artists’ dealings with nature. “We’re so overwhelmed with Magritte merchandise, his bird-leaf is a famous coffee cup today. I wanted to get beyond all that and rediscover the impression his paintings make on the viewer. Magritte was always trying to convey an idea. He wasn’t interested in the quality, the texture of the painting, and in fact his paintings are often quite rough as though he was in far too much of a hurry to make his point to consider the surface of the canvas.” Magritte’s Jeune Fille Mangeant un Oiseau (Young Girl Eating a Bird) (1927), a seldom-seen work, captures the artist’s mix of the surreal and real echoed throughout the show.

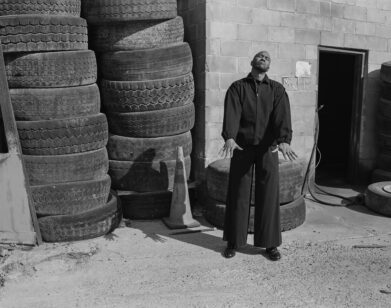

Punctuated with Demand’s shiny, mural-size photographs of his more-real-than-nature models, from a starry sky to an eerie lawn with every blade of grass standing at attention, or a bus shelter styled like a log cabin, “La Carte d’Apres Nature” is full of sly humor. This is intentional in Dutch artist Ger Van Elk’s video of a cactus getting a shave done for German television in the ’70s and Sigmar Polke’s series of palm trees made with balloons, glass and bread. But it’s also man’s vision of paradise, or ideal aesthetics, as in Robert Mallet-Stevens “cubist trees” in concrete designed for the garden of a decorative arts exhibition in Paris in the 1920s and the show’s wild card, Kudjoe Affutu’s coffin fridge. Demand went to Ghana to commission Affutu, who trained with Paa Joe, the internationally renowned coffin artist in Nungua in the Greater Accra Region.

And since 2007 Affutu has been running his own workshop. The wooden coffins, duplicating the shape of prized possessions, are a last hurrah for the deceased. And the satin-lined fridge, complete with back wiring, is the ultimate clash between man and Mother Nature.