The Builders Association

In 1994, Marianne Weems and her then-new ensemble, The Builders Association, presented Master Builder, an adaptation of the Henrik Ibsen play, on an upper floor of a New York City warehouse. She has since left Victorian dramas behind, blending live performance, video, technology, and architecture to narrate stories based on the experiences, facts, and phenomena of reality today. Her stage pieces have taken real-world concerns by the throat: psychic and geographical disorientation in Jet Lag (1998), global outsourcing in Alladeen (2003), and the datasphere in Super Vision (2005). The Builders Association’s latest production, Continuous City, which recently played at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, is a fable about place and placelessness, and how our experience of being constantly connected through technology alters our sense of distance, intimacy, and the world around us.

LOUISE NERI: Describe your theater background.

MARIANNE WEEMS: I was part of the V-Girls, an art performance collective of “academic guerrillas,” which we formed in 1985. I was also doing my own work in small downtown [New York] venues in the late ’80s. As well as being deeply influenced by the now-orthodox theater experiments of the Wooster Group, Richard Foreman, and others, I was obsessed with video work by artists like Tony Oursler, Gary Hill, Nam June Paik, and Gretchen Bender. Over time, I got some collaborators together and, in 1994, founded the ensemble on a large, impractical, un-tourable set of Henrik Ibsen’s The Master Builder. We built a full-scale, three-story house frame inspired by Gordon Matta-Clark’s collages and the deconstructed mail-order house in Buster Keaton’s One Week [1920]. I set the play inside the house with monitors, cameras, and actors moving from room to room. The audience watched from outside, and, after the performance, they were invited to come in and move through the house. This was the formative experience out of which the ensemble was born.

LN: But why Ibsen? Do you consider yourself to be, like him, a critical realist for your own time?

MW: Ibsen’s story has the kind of sledgehammer symbolism that I could use as a frame for a lot of materials without losing its essential structure. The story is rife with rich and familiar motifs-youth, death, desire, intimacy, entrapment—which I elaborated on through various lenses. Most importantly, on the set we experimented with a very primitive but lively electronic network of sound and video triggers that lined the house—the performers set off sounds, from breaking plates to falling down stairs, much like Foley artists. This also reflects my engagement with what [composer] John Cage described as making the invisible visible-materializing our struggle with the technology-saturated environment while playing on the social forces that construct us.

LN: How did you move from interpreting the work of others to writing your own material?

MW: Jet Lag was our first production based on contemporary, real-life stories. I juxtaposed two true stories about people severed from the conventions of time and space: Sarah Krassnoff, an American grandmother who flew across the Atlantic Ocean 167 consecutive times with her grandson to elude his father and his psychiatrist and who finally died of exhaustion from doing so; and Donald Crowhurst, the ill-fated yachtsman who disappeared in the course of a faked solo-circumnavigation of the world, leaving a haunting film and audiotape diary that charted his mental deterioration and increasingly delusional episodes. These stories brought their own contexts, thus my interests as a playwright shifted from interpreting the work of others to telling more urgent stories drawn directly from life.

LN: Each new work involves integrating expertise and innovation from outside the theater world. Why is this so necessary for you?

MW: My work often steps outside of the boundaries of conventional theater, especially with the collaborators that we choose. We have worked with architects Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio [on Jet Lag], dbox [on Jet Lag, Alladeen, Super Vision, and Continuous City], and the London-based international arts organization motiroti [on Alladeen]. Most unusually, we have partnered with several technology companies, including the National Center for Supercomputing Applications, and have even recently begun beta-testing for IBM. All of these interests result from my need to bring new tools to the job of storytelling. I try to combine entertainment with critical thinking by creating complex stage images that invite the audience to consider the expanding role of technology in our lives. I want technology to be both marvelous and completely obvious at the same time.

LN: I remember you once saying, somewhat perversely, that you dreamed of making theater without live actors. How do you feel about this now?

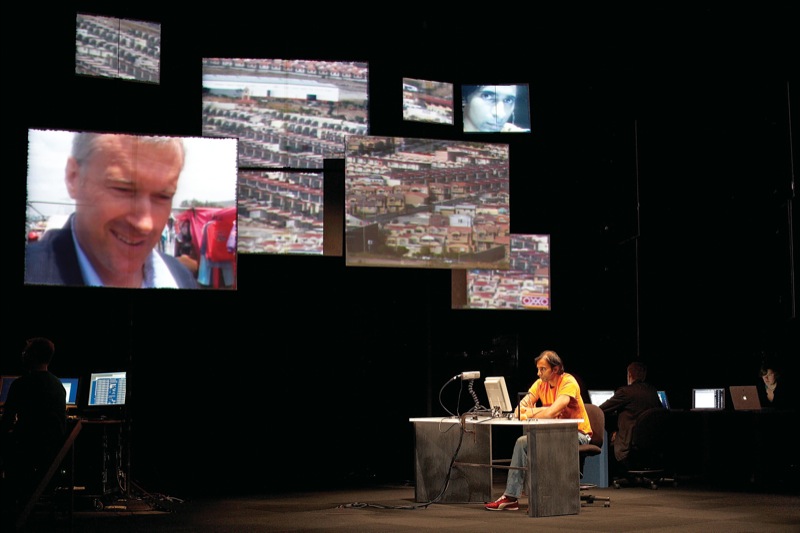

MW: There’s no substitute for the presence of real performers onstage, however it’s their interaction with “live” technology that gives our work its edge. Continuous City is dominated by screen presence. Across the set, footage plays that we shot over the past year in locations all over the world, from Las Vegas to Shanghai. An 8-year-old girl is an onstage character; her father is beamed to her onscreen from his ever-changing position in the world. In our ending, she finds that she’s perfectly happy to connect with him via video-chat; for her, his representation is enough. During the upcoming international tour of the piece, two performers will delve into every city on the circuit: Moe Angelos, by blogging about the places and people she meets on the road; and Rizwan Mirza, by video-chatting with his family, who are spread out between New Delhi, Paris, and New York. So we’re integrating the real cities we visit, the real people we meet in them, and the virtual cities interspersed between the real ones.