Tabitha Soren is Using the Residue of Human Contact to Make Sense of Our Virtual World

Photograph by Lou Noble

Touch in the age of the digital has undoubtedly become an anxiety. Not for want or lack, mind you. Fingers across the globe are working tirelessly — swiping, typing, touching — symbols of communication and connection. What has been displaced by the emergence of digital proxies in every crevice of humanity isn’t yet clear, though, for those of us who remember a time before screen time, this anxiety hovers over our digitized mediation of the world — a bit like a smudge on a screen. This metaphor is made literal in the work of photographer Tabitha Soren. Using a large-format Hasselblad camera, Soren has a made a series of images of images on a large iPad coated in the oily tracks of human fingerprints. Aptly titled Surface Tension, the series, which is on view at the Davis Museum at Wellesley College through June 9, is Soren’s attempt to create a visual dictionary of the “remnants of a haptic language” — haptics being the concept of touch and all its sensory implications. The concept of this special sensory mode is made vivid when Soren applies them to images of the uprising in Ferguson, Missouri or intimate angles of human expression. The photos, recognizable to all on their own, become intimate and coded underneath these oily tracings of human contact. Yet, in the intimacy of this pairing, one can see the entire world performing the same functions on their tablets and iPhone screenings, churning through all the content the world has to offer. The work bridges pop culture and fine art with a kind of finesse that seems uniquely fitted to Soren’s past work as a journalist for MTV News in the mid-90s covering Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign, before she moved onto a career with NBC News and ABC News. Now a well-established artist who is also married to Moneyball writer Michael Lewis, Soren sat down with Judith Thurman, the author and staff writer for The New Yorker. The pair discussed the difficult visualization of this digital moment on a cold February afternoon at Thurman’s Upper East Side apartment, but had the capacity to connect a confused present with a confounding past — specifically the handprints found in Chauvet Cave in Southern France, the subject of Thurman’s famous essay “First Impressions,” which became the inspiration for Werner Herzog’s 2011 documentary Cave of Forgotten Dreams. “Our screens and the way that we touch them are an attempt by people to enter into another world,” Soren told Thurman. “They’re our contemporary cave paintings.” —NATHAN TAYLOR PEMBERTON

———

JUDITH THURMAN: How did you get the idea for this project?

TABITHA SOREN: I was on a plane reading a PDF of a book. And because I kept making the same gesture on the screen to turn the page, there was a very graphic set of swipes on my screen when I powered it off. The light above my seat was harsh but it really highlighted all of the gestures on this black screen. I thought it was really lovely. So, I started taking black and white photographs of fingerprints and gestures on my iPad with my Hasselblad, using roll film on which each frame is 2.25 x 2.25 inches. I printed all these gorgeous, delicate, gelatin silver prints with a huge range of grays. But they couldn’t be very big because the negative wasn’t very large.

THURMAN: You’re describing a relationship with something almost archaic. You’re not anti-modern. It’s not anti-technology. But it is resistant. Part of the surface tension is between analog and digital.

SOREN: Resistance is at the heart of this project. I resist the joyless urgency of my time. I resist giving up shooting film. I seek out the slowness of the art-making process. And also, much to my children’s chagrin, I resist technology taking over my household. I managed to find a way to transfer those arguments into art. “Haptics” are the science of digital interactions with a touch screen. And it’s worth noting that the word “digital” also refers to our fingers. But “haptic language,” in another context, is the way that people and animals communicate and interact via touch. Touch is vital for survival. We die without it.

THURMAN: Surface Tension is, to me, an erotic title. Surface tension is the tension between two bodies that creates arousal. That’s the first thing that occurred to me. In a way, you’re bringing back the friction. It starts with the smoothness of this little gadget, and the glassiness of it. And the dirty fingerprints highlight the swiping and the sweat and the excretions of a body — its physicality. They create a surface for arousal.

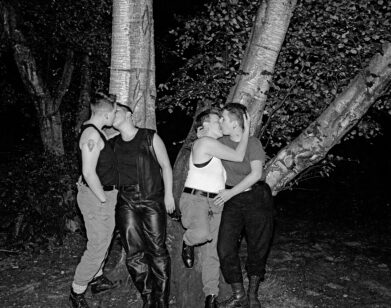

“Paradise Hill, Chloe Nicole,” 2016.

SOREN: I was thinking of it more as a contrast between humanity and machine. I do think that machines, in their perfection, make us feel insecure in our imperfection. Digital culture does encourage us to explore other worlds, but passively. You visit all kinds of places without leaving your seat. The access to knowledge is good, but I think it also seduces you, lulls you into a kind of inactivity and dependence. It’s the metaphor of a GPS. Instead of exploring on your own, following your instincts, you listen to a voice telling you to take the first left.

THURMAN: And the GPS isn’t infallible. I know New York geography better than it does! I often overrule Uber drivers when I know a better route.

SOREN: I live in Silicon Valley where technology and these perfectly designed devices are worshipped. The technology billionaires run the town, they own everything, they live in the nicest neighborhoods. The device in your hand or on your desk is a symbol of that aspirational culture. We’ve been programmed to think that they make your life better. In some ways they do, of course. But they can trick you into thinking that there’s no downside.

THURMAN: These images are a map of your activity and of your family’s. It’s a finger map, a map in swipes, a map in thumbprints, of how you spend your time. It’s the image of time itself.

SOREN: The pictures also make visible what we don’t see at all, like time slipping away. You sit down at your computer thinking you’re just going to answer a couple of emails, and then get back to real work — shooting or editing — and hours later, you have wandered off mentally. It’s the opposite of “mindfulness.” What kind of life is that? I had never seen an attempt to visualize that lost time, so I thought I might take a crack at it.

THURMAN: You could name the project after Proust: In Search of Lost Time.

SOREN: The PDF swipes and the video game hits and the sweat from my son all look very different to me now after doing this for so many years. I can tell the difference between my own typing and someone else’s. And typing looks different from playing a game. I can read these photographs like a map now. I actually can tell what specific action was performed on the device.

“Jon Wurster FB,” 2014.

THURMAN: There’s a really interesting tension in the work between the notion of being touched and being untouched. And when you’re looking at the feed of endless images of war and suffering online, you remain untouched. In these photographs, you’re highlighting the tension between hands off and hands on.

SOREN: Scale helps quite a bit. By blowing up the image and framing it, I can direct the gaze. My camera makes it easy to see actual flesh and germs as well as the imprint by a human being on this event. It’s about social justice as much as technology.

THURMAN: There is also a play between the ephemeral — the constant swiping and moving of the image — and the imprint of the hands, which goes back to the first art that humans made, the handprints that they left in caves.

SOREN: I’ve been working on this for five years and every so often, you have a moment of, oh, you know, this is g-o-o-d. This connects to something that’s really important and way bigger than me and way bigger than the art world at this very moment. It’s connecting to a zeitgeist in a way that I couldn’t have planned. That’s why your New Yorker essay on the handprints in the caves of Spain and France moved me so much. I felt a connection to history.

THURMAN: Actually, most of the representations in caves are handprints. There aren’t that many animals. You think of the animals because the animals are more exciting. But there are many, many, many more hand prints than there are animals.

SOREN: Why do you think they were making hand prints?

THURMAN: Nobody knows why they made these pictures or what the pictures mean. If all the members of a community leave handprints on a wall, it probably marks the space as sacred, or at least, ceremonial. There are handprints of babies, too. The prints are stenciled, in some cases — they blew pigment at the hand and left an outline. In other places, the prints were painted. But whatever the prints mean, making them was an act of touch. What are they touching? We don’t know any more than people in the future would understand what you meant if these works of yours showed up in a time capsule 40,000 years from now, without explanation.

SOREN: Were the Stone Age handprints an attempt to mirror something?

THURMAN: Again, no one knows. Some pre-historians have ventured to say that the caves were a spirit world, and that people may have believed the spirits dwelled inside the rock. They also used the rocks to suggest the contours of animals. Perhaps, the hands were summoning the spirits of the animals.

SOREN: I feel like our screens and the way that we touch them are an attempt by people to enter into another world. They’re our contemporary cave paintings.

THURMAN: Your work articulates a feeling I have that we are living at a moment of critical change in perception, and in how we perceive. There’s a shift from the verbal world, and the tactile world, to the visual world — a sphere in which our lives take place on a screen. The eyes have it, in other words.

SOREN: Yes, I think that our reliance on technology is making us more visual than verbal. I definitely see it in my teenage daughters, who conduct their social lives almost exclusively through the images on their smartphones. There’s a picture in the (Davis) museum show called “Emailed Kiss Goodnight.” I was out of town and my daughter wanted to kiss me goodnight, and it didn’t occur to her to call me, to speak with me. She just pulled her iPad up to her face in bed, blew a kiss into the camera, and then sent me that JPEG. That image in the exhibition really sums up the idea that we are becoming virtual: We are JPEGS and lols. Even our laughter is virtual.