Society Observed

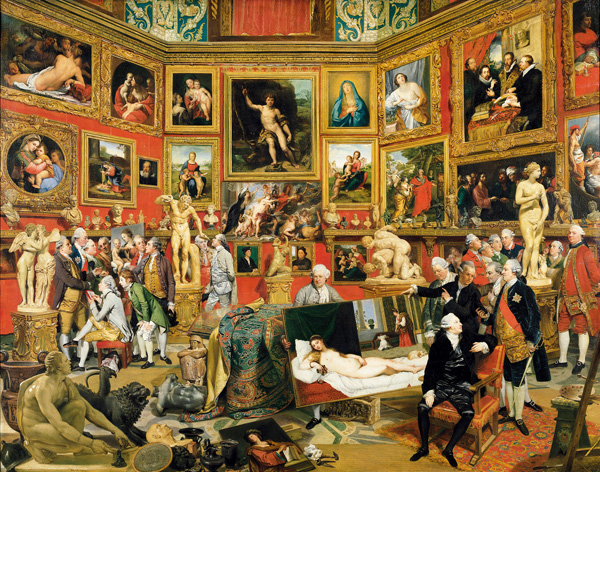

ABOVE: Johan Zoffany, The Tribuna of the Uffizi, 1772-77, oil on canvas, The Royal Collection ©2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Art Basel Miami Beach, this country’s most important contemporary art fair, is now officially open for business and pleasure, revelry and regret. For those staying put in the leafless cityscapes of New York, the alternative to consider is a journey up north, across the ocean, and back in time.

Less than two weeks had passed since George Washington led the Continental Army to a rousing victory at Trenton when Johann Zoffany, a German-born painter and one of the founding members of the Royal Academy of Arts in London, was made Baron of the Holy Roman Empire—a mark of appreciation for his sumptuous portrait of the Grand Duke of Tuscany and his family. Zoffany, best known for his conversation pieces, as informal group portraits of noble (or wealthy) families came to be known, is the namesake of one of the best exhibitions this winter, at the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven.

Johann Zoffany RA: Society Observed—the show’s latent qualities telegraphed by the fantastically epigrammatic subtitle—digs deep into the social and political vicissitudes of the late 18th century: the gathering momentum of Enlightenment, the evolving edifice of the British Empire and Georgian England, the French and American revolutions.

Set against this neurotic backdrop, the first visual clues are suggested by “Self-Portrait with the Artist’s Family,” Zoffany’s last known painting, made c. 1802 or just before his 70th birthday. After climbing up the museum’s serpentine staircase, the visitor intially trudges past the piece, mounted on the reverse side of a concrete panel. Compelled to turn around, he now faces the bespectacled artist: Zoffany is gazing lovingly at his wife, flanked by his five daughters. The eldest, Maria Theresa, is seated at a harpsichord—fingers on the keyboard, eyes turned away from the open score; two younger girls appear to be plucking the harp. In opening the show with this pirouette, the curators communicate both the politics of reappraisal at the heart of Society Observed and a series of hints of what is about to unravel: realism fueled by the painstaking attention to detail, portraiture as a key area of interest, and the passion for music.

Society Observed unravels through a grid of open bays, the carpeted flooring sectioned off by ribbons of travertine marble. Some pictures hang on white oak panels covered with Belgian linen in beige or steel blue; some on tall, concrete dividers. Each and every one bathes in the warm glow of natural and diffused light. Co-organized by the Royal Academy, which seems to have raked through its vaults to come up with a number of obscure or unknown pictures, and where the show is due to travel in March, the show has rallied an impressive roster of lenders that includes Tate Britain, Galleria Nazionale di Parma, and Museen der Stadt Regensburg—a list which, as it happens, tracks Zoffany’s own wanderlust and travels.

Compared to his signature society portraits, most pieces from his early period are quite startling, dripping with telltale signs of the visual lingua franca he internalized in settecento Italy: “The Three Graces” is a compact riff on the theme familiar from Botticelli, Rapahel and Rubens—a precocious exercise in art-historical awareness; his only known still life is flimsy, especially if placed side by side with, say, a Chardin; “Venus Marina,” his last painting before the relocation to England, depicts, yes, the goddess of love emerging from the sea, recumbent on an oversized scallop shell. The catalog illuminates the latter work’s patchy provenance: most likely commissioned for the bedroom of the Archbishop-Elector of Trier, it vanished following an attack by French Revolutionary troops in 1794, when the palace was used as a hospital and barracks.

Time and again Zoffany finds himself narrowly ahead of the unrelenting thrust of history: his arrival in London, in the fall of 1760, will necessitate focus and lead to financial and critical success, though it never quite reins in his protean style—the irreverent sense of humor; the free-form maneuvering between Baroque, Rococo and Neoclassical traditions; and the tension between Central European melancholy and British imperial optimism.

David Garrick, a theater actor and producer, became Zoffany’s first major patron in England. Some of the resulting pictures, specifically the genre paintings, can, despite some charmingly operatic characters and intricate renditions of the mise-en-scène, feel a little stale: the subject comes across as an exhausted Rococo fad, a reaction to the glum seriousness of the Baroque. “Mr. and Mrs. Garrick by the Shakespeare Temple at Hampton,” one of a suite of four related works (two of which are being auctioned off by Sotheby’s in December with a steep estimate of about 10 million dollars), is more interesting. One of Zoffany’s first shots at a conversation piece, it shows the Garricks relaxing next to their riverside, custom-built pantheon devoted to the playwright: a stately spaniel in the foreground, the young Master gamboling on the temple’s steps, a transfixed servant near the picture’s edge as if on perpetual standby.

A host of commissions would follow, spurred by an outsider’s aptitude for courting both the peerage and the rising bourgeoisie. “The Sharp Family,” a vertiginous composition from 1779-81, crowds 15 sitters (and a dejected-looking dog) on a river barge where the family held their celebrated Sunday recitals. The piece showcases those qualities that made Zoffany so popular: the liveliness of expression, the richness of color, and a sense of unity achieved despite so many disparate subjects engaged in unique activities.

His renderings of musical instruments are also strikingly precise: the centrally positioned fortepiano; the basalt-hued, shapely serpent; the rounded lute; a pair of French horns and flageolets; and two sets of sheet music. The community of German émigrés in London, which included his future friends, Johann Christian Bach and Carl Friedrich Abel, was certainly a factor in Zoffany’s decision to settle in London, and the recurrent translations of this fondness for music into the visual idiom are one of the show’s most charming motifs.

Also noteworthy was “The Drummond Family”, which underwent RTI treatment, an imaging process that allowed curators to generate a topographical map of the painting. It reveals, tracing the protruding seams alongside the canvas, how Zoffany pedantically cut and stitched four fragments of his preexisting works into the piece. It also shows a great deal of overpainting, shedding light on his struggles with arrangement and scale, and the degree of creative control it took to produce these great works. A nearby video projection documents this joyride of discovery.

A group portrait of the Royal Academicians, from 1771-72, depicts a claustrophobic chamber densely packed with men, rendered in ashen greys and umbers, with busts and statues of male figures lined up on the mantelpiece. (The annotated key identifying the represented figures is a nice touch.) The picture feels accomplished yet oddly charmless. That may also be its intended effect: the work is a good example of Zoffany’s talent for registering the daily minutiae—and hypocrisies—of his adopted country.

Having gained the patronage of the royal family, Zoffany must have felt a degree of resentment from his peers. His refusal to submit to the Academy’s customary process of nomination and election didn’t help (he was recommended by the king instead.) Today some of his contemporaries—Joshua Reynolds, the Academy’s first president, Thomas Gainsborough, William Hogarth—have, justly or not, far eclipsed Zoffany in reputation and popularity. There are 11 paintings by both Reynolds and Gainsborough in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s permanent collection; there is but one by Zoffany, bequeathed in 2006.

Two 1771 solo portraits of the royal couple compel the viewer to ponder Zoffany’s relatively cold reception: they exude an irresistible sense of gallantry (and that both have been secured on loan, hung side by side, and given plenty of wall space is yet another mark of this show’s curatorial flair.) King George III poses seated, casually leaning on the adjacent side table, his bearing nonchalant and accessible, off-duty and masculine. Queen Charlotte gazes nobly at the viewer, hemmed in by the superb detail of her Vandyke dress and the aubergine-colored drapery floating above. In composition and color, the pairing feels far worthier a representation than Thomas Struth’s obtuse photograph of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery earlier this year.

Zoffany’s fortunes declined with another royal commission: a painting of the Tribuna room at the Uffizi in Florence, which housed one of the greatest art collections in 18th-century Europe. The queen deeply disliked the work (now considered one of Zoffany’s finest, and, regrettably, not on view), and the resulting termination of patronage took Zoffany on more trips: to Italy and Austria, where he painted a number of conversation pieces for the Hapsburgs, and to Bengal India. The exhibition concludes with two history paintings from the 1790s that comment on “the democratic cruelty” of the French Revolution, a poignant departure from painting politeness.

Peter Schjeldahl of The New Yorker recently described art fairs and biennials as “tourist-luring, physically and mentally exhausting, spiritually entropic institution[s].” Some of the related to-do can indeed be jarring. (Case in point: some of this writer’s Florida-bound acquaintances have already begun plotting their Brazil itineraries, naturally, for the Sao Paulo biennial—in December 2012). Society Observed makes one grateful to have skipped the circuses of Sao Paulo, Basel, or Miami: two hours on Metro-North, away from the frenzy of New York’s art bubble, Schjeldahl and fellow discontents will be rewarded generously.

Johann Zoffany RA: Society Observed is on view at the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven through February 10. It reopens at the Royal Academy of Arts in London on March 10.