Radical filmmaker Charles Atlas on Leigh Bowery, porn, and performance

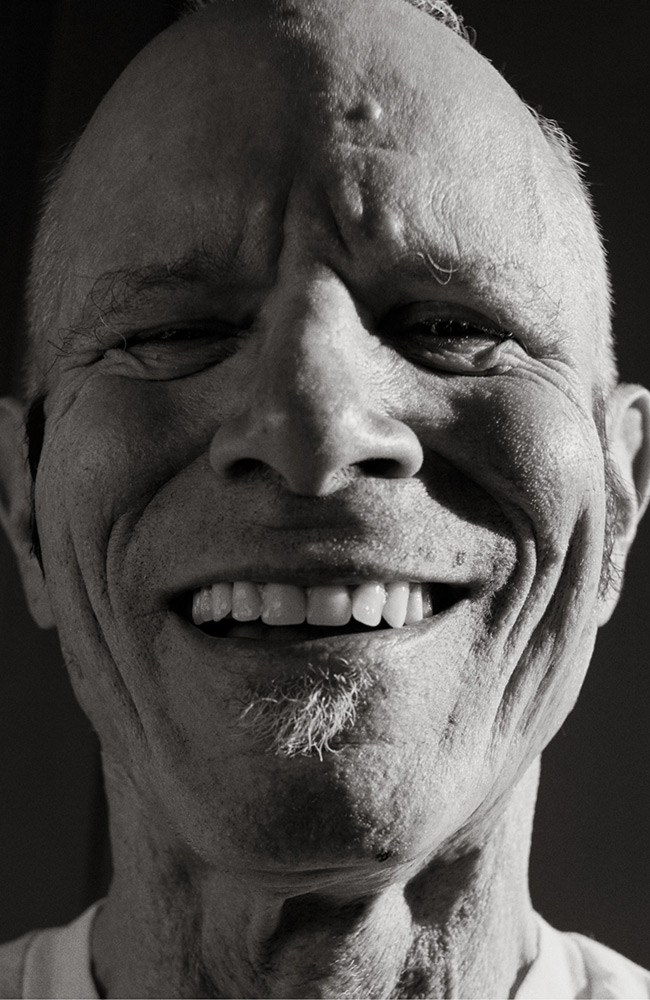

In this time of posting and tagging and filtering, the idea of filming live dance, filming life itself as dance, and choreographing and documenting various segments of the cultural underground, all seem like a vital part of artistic production. But back in the early ’70s, Charles Atlas pioneered an entirely new film practice by using the language and movement of contemporary dance and performance. Atlas was 20 when he moved to New York City from St. Louis, and soon became the assistant stage manager, and then the production manager and lighting designer, for the legendary Merce Cunningham Dance Company. It was there that he not only got a master class in the avant-garde, but also met several of the dancers and artists who would become his collaborators. In 1973, he went on to become the company’s official filmmaker-in-residence. While so much experimental film of the time was about stripping away the “theater” of cinema for more minimalistic or formalistic pursuits, Atlas’s radical film works celebrated the body, movement, music, lighting, projection, personality, campy wit, and the individual gesture—basically instead of trying to isolate the medium into pure film, his brilliance was fusing it with the larger artistic ecosphere. Often, he created portraits of the under-represented, the extremists, and those massively talented performers seemingly born to be captured by Atlas’s lens. Among his most revered productions is 1986’s phantasmagorical Hail the New Puritan, an outrageous, hard-core, faux vérité joyride of stylized subversion and unmistakable gay sensibility starring his longtime collaborators Michael Clark and Leigh Bowery.

Atlas is at heart an inveterate experimenter, jumping across mediums (gay porn, music videos), exploring new technologies (live editing, real-time two-camera portraits), and basically shuttling among so many avenues of creation (gallery, screen, stage) it’s nearly impossible to delineate his process. This spring, he comes back to a familiar venue, New York’s the Kitchen, to stage a multipronged, multi-multimedia exhibition. It will include two new works incorporating video portraits, and “The Kitchen Follies,” an Atlas-directed “variety show” of new and older work, edited, blended, and projected on the spot. One longtime friend and early collaborator, the iconic multihyphenate dance artist Yvonne Rainer, met up with Atlas in his downtown studio to discuss their many lives as artists and renegades on the stage and off.

YVONNE RAINER: You seem to have total recall of even your very early work.

CHARLES ATLAS: It’s funny. I don’t have that great a memory about things in my life, but my work I remember. I can remember nearly every edit of the films, which is all of my early work, because they were so worked over.

RAINER: When did you come to New York?

ATLAS: 1969. I started working with Merce [Cunningham] in 1970.

RAINER: And then you and I first worked together in 1972 when you staged-managed my piece This is the story of a woman who… But I want to start by talking about Hail the New Puritan, from 1986. I have a clear memory of seeing and being so impressed by it. I guess it was my introduction to a certain aspect of your work, specifically your endless attraction to and curiosity about the outrageous and outré.

ATLAS: A lot of my collaborations grew out of the people I knew in Merce’s company who went on to do their own work. People like Karole Armitage and Douglas Dunn. I was drawn to the fringe.

RAINER: To the margins.

ATLAS: I guess I just like extremes. I felt “extreme” meant it was more progressive in some way.

RAINER: Outcast culture is always more provocative and challenging. But it’s interesting that what you were doing was so extreme in relation to what was going on in the art world, especially with minimalism, as well as with the classicism of Cunningham.

ATLAS: I was consciously not minimalist. And as for Merce, I started so young with him and easily adapted to the Cunningham-[John] Cage aesthetic, although I really rejected the Cage part of it.

RAINER: Oh, really?

ATLAS: I tried [Cage’s] chance method, and it just didn’t work for me. As people used to say, you were either a Merce person or a John person. I was a Merce person.

RAINER: And I was a John person.

ATLAS: Well, John never cheated. Merce did because he was a Catholic. [laughs] But as it turned out, later on when I started working with live video, a lot of chance came into the work—because the medium of video is so uncontrollable.

RAINER: John never ruled out accidents. In fact, his whole philosophy was about accepting the random and the accidental. That’s certainly an influence on my work. There are set moves, but the sequence is totally up in the air, so every performance is different. Let me ask you about Leigh Bowery and his ultra outrageousness. I can’t think of anyone more extreme than Leigh.

ATLAS: That was conscious. He died so young. He was only 33, still rebelling against his parents, so he never made any compromises. He came from a Salvation Army background.

RAINER: Totally repressive. It becomes a lifelong mission.

ATLAS: Most people who were very rebellious in their younger years calm down a bit and then people are disappointed.

RAINER: He didn’t live long enough. I saw an image of him doing a performance where he gives birth to a naked woman. How did he pull that off?

ATLAS: The main thing was that before he gives birth, he sings a song and jumps around the stage with this person attached to him. [both laugh]

RAINER: What was it like to walk down the street with him in one of his outfits?

ATLAS: It was memorable. It’s funny—the people on the street usually got it. They were like, “Right on.” And then other people were shocked. He always stayed with me when he came to New York, so for years there was glitter on the stairs that wouldn’t come off. [laughs] He used to dip his hands in glue and then put on glitter gloves. He also did that one look where he was wearing nothing but this big bra and a merkin, with platform shoes and his bug headpiece. And this was in winter, so it was really cold. The looks always involved some degree of pain.

RAINER: Was there a masochistic aspect to it?

ATLAS: Yeah, sadomasochistic—both ends of it.

RAINER: You’ve worked with so many kinds of performers and in so many art forms, even when you’re just winging it with no money.

ATLAS: At the beginning, it was really just different dancers, but each project was different. I even tried to write a regular film script with a partner [Mira Kopell], but after a couple years we gave up on it. You go to a meeting with producers or these professional meeting-goers, and it’s always the same. The film was called Migraineia. It was about a romance between a female anaesthetist and a male stage hypnotist. It was about pain and ways of avoiding pain. They used to do operations with just hypnotism, which shocks me.

RAINER: I’m always interested in the stories that got away.

ATLAS: The problem was that, after two years, I got too frustrated. These people who do feature films have an idea that it takes five years. I was like, “How could I be interested in the same idea in five years?”

RAINER: What brought on your collaboration with Karole Armitage? You two worked together quite a bit over the years.

ATLAS: Karole and I had been friends from the Cunningham days. At the beginning, I did the lights, costumes, and sets for her dances. We worked together with the Paris Opera, which took me to a whole different level of that other, nonfilmmaking part of my life. You know, I still do lighting for Michael Clark, but he’s really the only one, because it keeps me in touch with him. I usually see him once a year.

RAINER: You move so easily from one milieu to another. It’s like a network with your social connections.

ATLAS: Almost all of the early work I did was with people I knew well. These days I don’t leave the house, so I don’t know anyone. [laughs] I just go from one thing to another, because I’m afraid to turn things down, even though I’m so busy.

RAINER: Do you work on more than one project at a time?

ATLAS: I try not to. I have a show in Zurich coming up and then a show at the Kitchen a month later, so there’s no way I can do all new work for the Kitchen. I’m going to show different versions of two pieces I’m making, plus a live video with performance art. I just did a big live-video piece at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. I’d been working on it for two and a half years, and it was such a major effort. It starts out as a 3-D dance film—I’d always wanted to work in 3-D. And then there’s a break with live dancing and three live cameras and me mixing projections on a screen, so you can see all of it at once. It is so hard to do. And I’m doing all of these effects on top of the footage on the spot.

RAINER: So you’ve honed your skills as you’ve gone along?

ATLAS: I’ve learned everything on the job. I never went to school for anything. Even now when I sit with someone who’s doing technical things on the computer, I learn so much. I did a big commercial job for Calvin Klein two years ago. They asked me to make a film of the collection. The men’s and women’s collections were so different, so I decided to do two different films. It was the most luxurious working experience I’ve ever had. They had an art director who built the set and everything. It was so different from the art world.

RAINER: I have to up my prices. I was just looking at stills from your 1973 film Mayonnaise Number One, with Douglas Dunn. They are lovely images.

ATLAS: In my youth, I had loved Manet’s paintings, so I thought, “I want to do a film for every painting.” [laughs] It was a boy with cherries. I didn’t show him the painting. I don’t know if I even told him about it. I just directed him. I must have told him it was Manet. But I made the costumes and the sets, and there were different versions based on the colors and shapes in the painting. And then I had him lean on the sawhorse. I also did a second one that I’ve lost. It was called Mayonnaise Number Two, and in it my therapist played the piano as Manet’s wife. It was very interesting to go on the other side of therapy where you’re not the patient. She was an older woman and was very sensitive about covering her arms, because in the painting, Manet’s wife is wearing sheer sleeves.

RAINER: Do you still go to a therapist?

ATLAS: I stopped a long time ago. I went to two different therapists in two different periods of my life, but the idea of therapy is you’re supposed to get better. [both laugh]

RAINER: Depends on what you mean by “better.” Tell me about that fantastic sex-and-death film you did with John Kelly, Son of Sam and Delilah [1991].

ATLAS: That came about because I had the very ambitious idea of doing a long-form television piece, like an hour and a half. I would develop the material in performance, and then that would be the material for a film. We never got funded, of course, so we went ahead with the performances, and my part was doing the film.

RAINER: I remember the final scene with John Kelly the most.

ATLAS: You mean, where they all get shot in the discotheque?

RAINER: No, no. Samson [Almon Grimsted] is in the bed and Kelly, who is dressed in drag as Delilah, is singing to him. I worked with Kelly’s pianist, Fernando Torm Toha. It reminds me of some of the Cage acolytes who destroyed the instruments that they were trained on, like Nam June Paik with the violin. Fernando once did a happening at 112 Greene Street in the ’80s. He had a grand piano brought in and he split it with a chainsaw. There was also the story of a pianist in Stockholm who took a chainsaw to the piano. It slipped and he cut his leg. It was all about musicians rebelling against their training. That happened in dance, too—with Steve Paxton, Barbara Dilley, and Trisha Brown. Me, not so much. I was more omnivorous. I used everything I learned. Anyway, John Kelly’s aria at the end of your film is so beautiful and poignant, especially at the time when so many around us were dying. And then a few years later you did this porn film, Staten Island Sex Cult [1999]. Has it been shown?

ATLAS: It’s been sold at porn stores. I don’t know if you can buy it anymore. I guess I want to do everything. I was in a producer’s office and someone said, “Let’s do a series of artists doing porn.” And I was like, “Sign me up.” [both laugh] And we did. I don’t think they ever did another one.

RAINER: Another example of your identity as an omnivore.

ATLAS: It was really interesting to do because, how many times in your life do you encounter something that is really fresh? Directing porn was really fresh. It was a challenge. We found a brothel in Staten Island that we shot in.

RAINER: Did you make the crew leave the room?

ATLAS: No. That was for the sex scene in Hail the New Puritan. But I will say about Staten Island Sex Cult that I learned a lot on that film. I would make a second one much better. I’m probably the only person who ever did a porn and did not make any money on it. [laughs]

RAINER: You didn’t try to market it?

ATLAS: It was nominated for the best porn comedy [at the AVN Awards]. [laughs] It was funny. It was around the time of Heaven’s Gate, the cult that thought they were going up to the spaceship behind the comet and they all committed suicide. That was how the porn ended, people disappearing and going up to the spaceship and leaving their sneakers. It was influenced by The X Files, the Heaven’s Gate cult, and Andrew Cunanan’s killing of Gianni Versace. Also I had women in it, not in the gay sex scenes, which you’re not allowed to do in gay porn.

RAINER: Now I want to ask, what is Ocean [a film capturing the 2008 performances of Cunningham’s 1994 dance work of the same title]? Douglas Crump told me it was one of his favorites.

ATLAS: It’s a film I did. Merce did a piece in the mid-’90s that was based on an idea of John’s. It’s a very long dance in the round. It lasts 90 minutes. The audience is surrounding the dance and then above the audience is an orchestra of 112 pieces. It’s a live piece. I was asked to make a film of it. Normally, when I had done documentation of Merce’s work, there wasn’t an audience. That’s so we could do multiple takes and could rehearse. This was done in a quarry outside of Minneapolis. I had a plan of five cameras. Originally, my idea was to put the audience in the middle and have screens all around to do a multi-channel experience, but I didn’t have enough material due to rain. Instead I decided to do two films, one that really respects the choreography and one where I intervened more. Then I decided I’d just make one film and have everything in it. That’s how it evolved into its 100-minute form.

RAINER: How old are you?

ATLAS: 68.

RAINER: Oh, youngster. You know how old I am? 83.

ATLAS: How is it up there? [laughs]

RAINER: Creaky. I try to exercise. Do you exercise?

ATLAS: No. I should do more.

RAINER: You’ve spent most of your life sitting.

ATLAS: Yes. But I always lose things, so I’m looking for things all the time. That’s my exercise. Going back and forth.

YVONNE RAINER IS A PIONEERING DANCER AND CHOREOGRAPHER, AS WELL AS WRITER AND FILMMAKER.