Up to Great Good

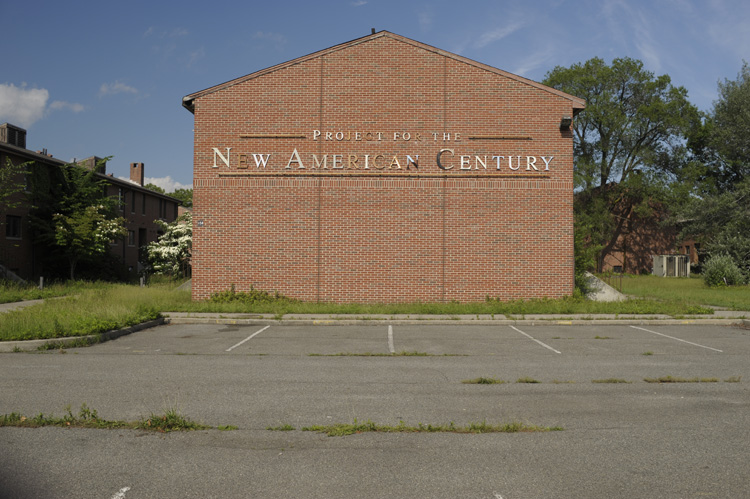

Tue Greenfort, Project for the New American Century, 2009. Photo by Charlie Samuels, courtesy of Creative Time

Governors Island has long held the psychic space of New York at its most unresolved. The island, a former military facility, has been virtually unoccupied for years; various attempts to figure out what to do with it have proven less than triumphant. Finally, there is a project that both honors the island’s history and reframes its landscape, and previously inaccessible buildings, to more peaceful ends. This summer, Creative Time has inaugurated a new public art quadriennial (that means every four years) PLOT, to celebrate the island’s landscape and architecture. PLOT’s first edition, the Mark Beasley-curated This World and Nearer Ones, explores some of the island’s more moribund themes. Adam Chodzko’s video installation depicts the imaginary discovery of a game played by the island’s former residents; Edgar Arceneaux’s ghostly sound piece is a poem of remembrance. Taken together, the the works signal an exaltation of the spiritual life of the island, and perhaps of the artists themselves, coupled with the dueling imperatives of looking back and moving forward.

AIMEE WALLESTON: All the works presented in this exhibition are site-specific. When you were planning the layout of the show, did you incorporate the artists in the process of deciding where each of their works would be shown? Or did the work itself kind of dictate where it would best be shown?

MARK BEASLEY: When you’re out on the island and you have only two hours to look at everything and plan what you want to do, it just made sense for me to have two or three buildings where I just said, “OK, well these artists make work about this, so, this work could fit.” In the case of the work of Krzysztof Wodiczko, the Magazine Building in Fort Jay just seemed like a perfect marriage. He’d shown me a version of the work, Veteran’s Flame, which is a projection of a naked candle flame with a voiceover of Iraqi and Afghanistan veterans. If you’re going to have a work that’s as loaded as that, than the site should equally suggest some way of reading the work. With A.A. Bronson and Peter Hobbs’ Invocation of the Queer Spirits [a séance ritual held two days before the show’s opening], we basically sat in a little cart and drove around the island, and we were led by A.A.’s response to the spirit life of the island, which was quite an incredible experience in and of itself. And with Klaus Webber’s Dark Windchime [the work has been tuned to the diabolus in musica tritone, a musical interval which has been believed to summon the devil]—that was very much led through a remote discussion, where I took pictures of different sites and then sent it to him.

AW: Were you interested in presenting this show, an ostensibly serious one, in the context of a summer show? It’s not a typical time for serious shows.

MB: In many ways, it was the artists responding to the site. But they are artists who are critical of the spirit of the age we are in. What fascinates me about the younger artists included, like the Bruce High Quality Foundation collective, is their critical response to the time we’re in now. They have a different response than more established artists in the show, like Lawrence Weiner or Anthony McCall. I was really interested in commissioning younger voices: They’re recently out of art school, so what does that mean now? The market is what the market is now. What does that mean for practices that have been created with the idea that ultimately they’ll be straight into Chelsea? With Bruce High Quality [their film, Isle of the Dead, is shown at the island’s abandoned movie house], their critical response is less about the market crash. It’s more about the position of a cultural producer in New York. They’re exploring how a younger practitioner goes about operating in a city that’s one of the most expensive places to inhabit. Their zombie movie is talking about how, as younger practitioners, they operate or don’t operate in the face of what is almost a zombie culture. It becomes a satire of this idea of always speaking with “a corpse in your mouth,” the idea of nostalgia as a corpse. I think, by making a zombie film, they’re going so overboard in overplaying that idea of looking back to the past that they’re actually trying to kill it. It’s very Oedipal: Kill daddy so the kids can play.

AW: You also have an audio piece, Message in a Bottle, by Patti Smith and her daughter Jesse Smith. And with that work, you have the celebration of the union of family and of different generations. It’s also the exaltation of an authentic icon, Smith, who is known to produce works that deify other artists-Rimbaud for example. Smith’s very much about heroes.

MB: The first time I heard got to know about Rimbaud, or William S. Burroughs, was reading about Patti Smith. I think, in other decades, this idea of quoting the past was about putting up little flag posts. If you really wanted to get into a counterculture, you had to work at it, and those flag posts were there to help. But now, we live in a time where it’s all available, it’s all on the Internet, so one’s relationship to that idea of counterculture is very different. You don’t have to struggle to find your alternative.

AW: And perhaps that alternative is coming more from within, rather than from outside cultural forces?

MB: Perhaps, yes. This is a very oddly spiritual show, in the end. Maybe this is my mid-life spirit moment.

PLOT opens June 27, 2009 with a reception 2–4 PM. You can reach Governors Island by The Governors Island Ferry, which departs from the Battery Maritime Building, adjacent to the Staten Island Ferry Terminal.