STUDIO VISIT

Painter Jenna Gribbon Is Still in Her Honeymoon Phase

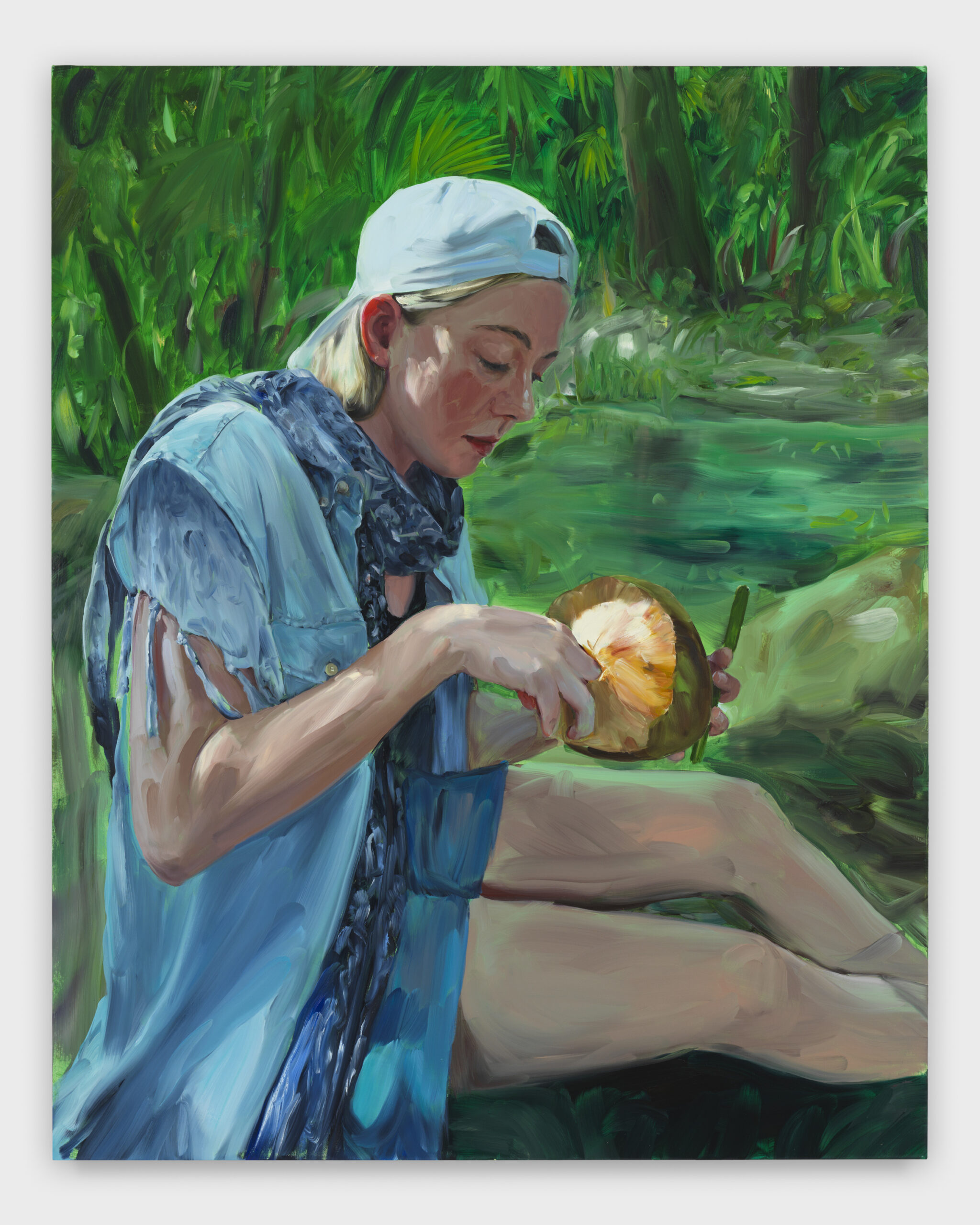

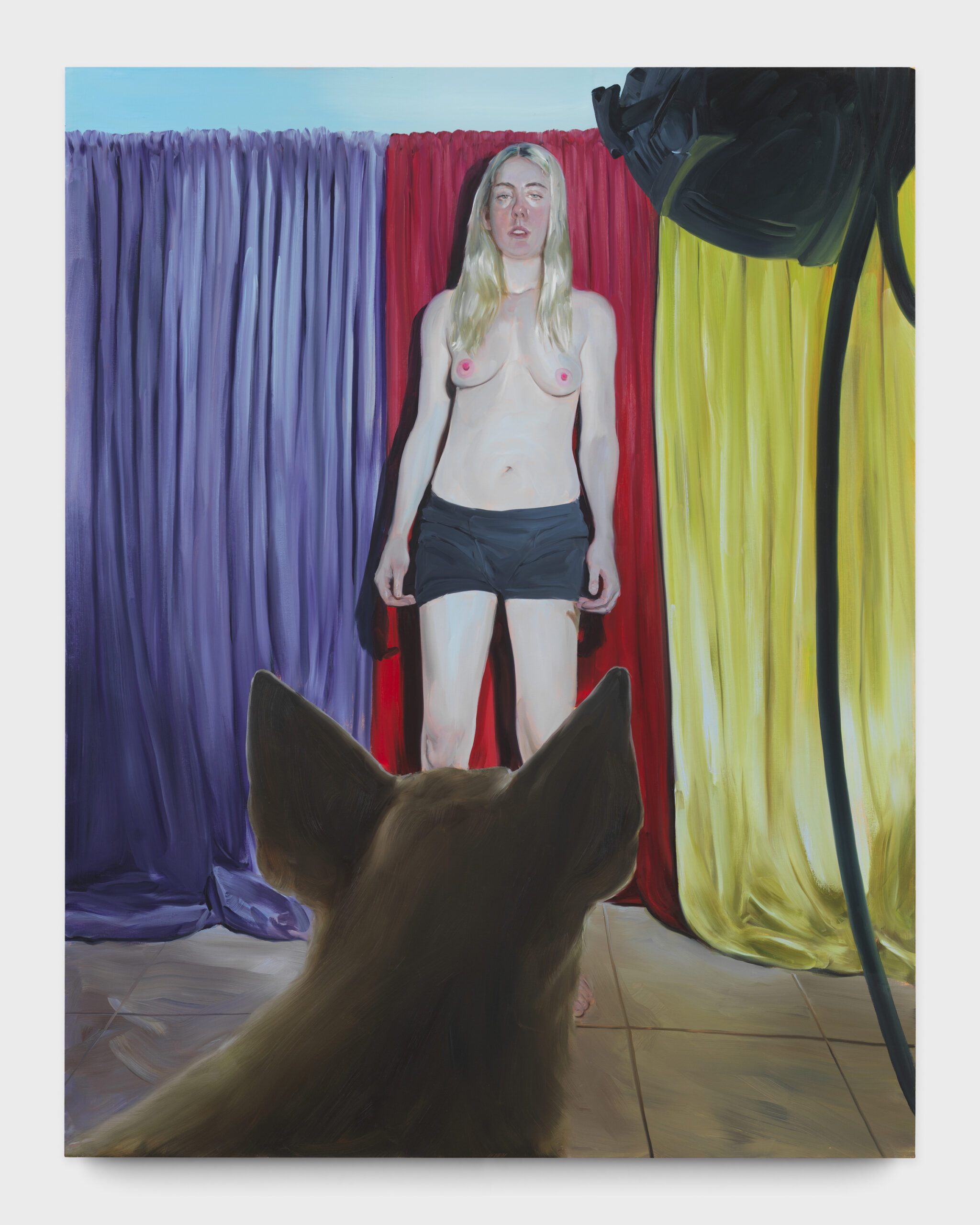

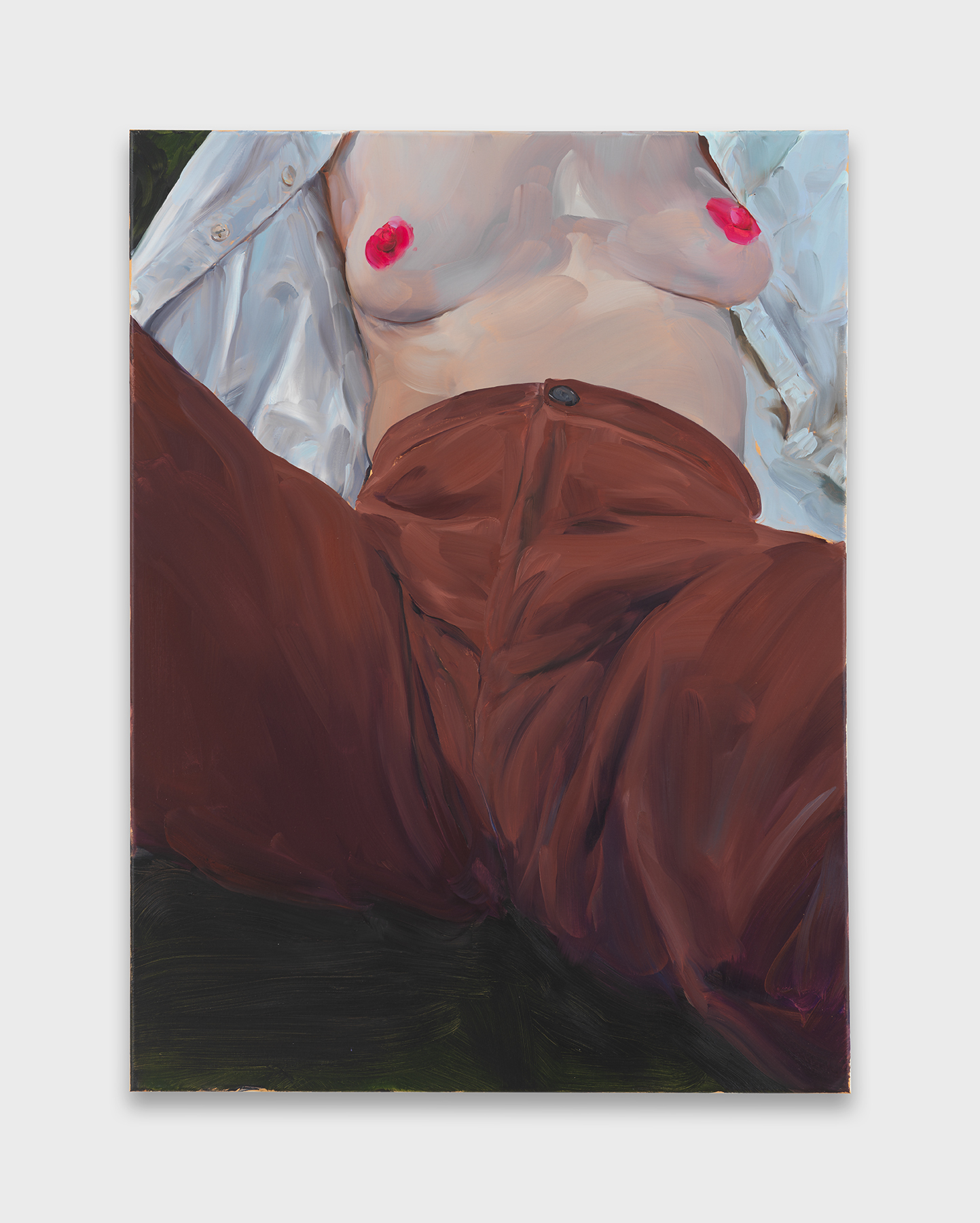

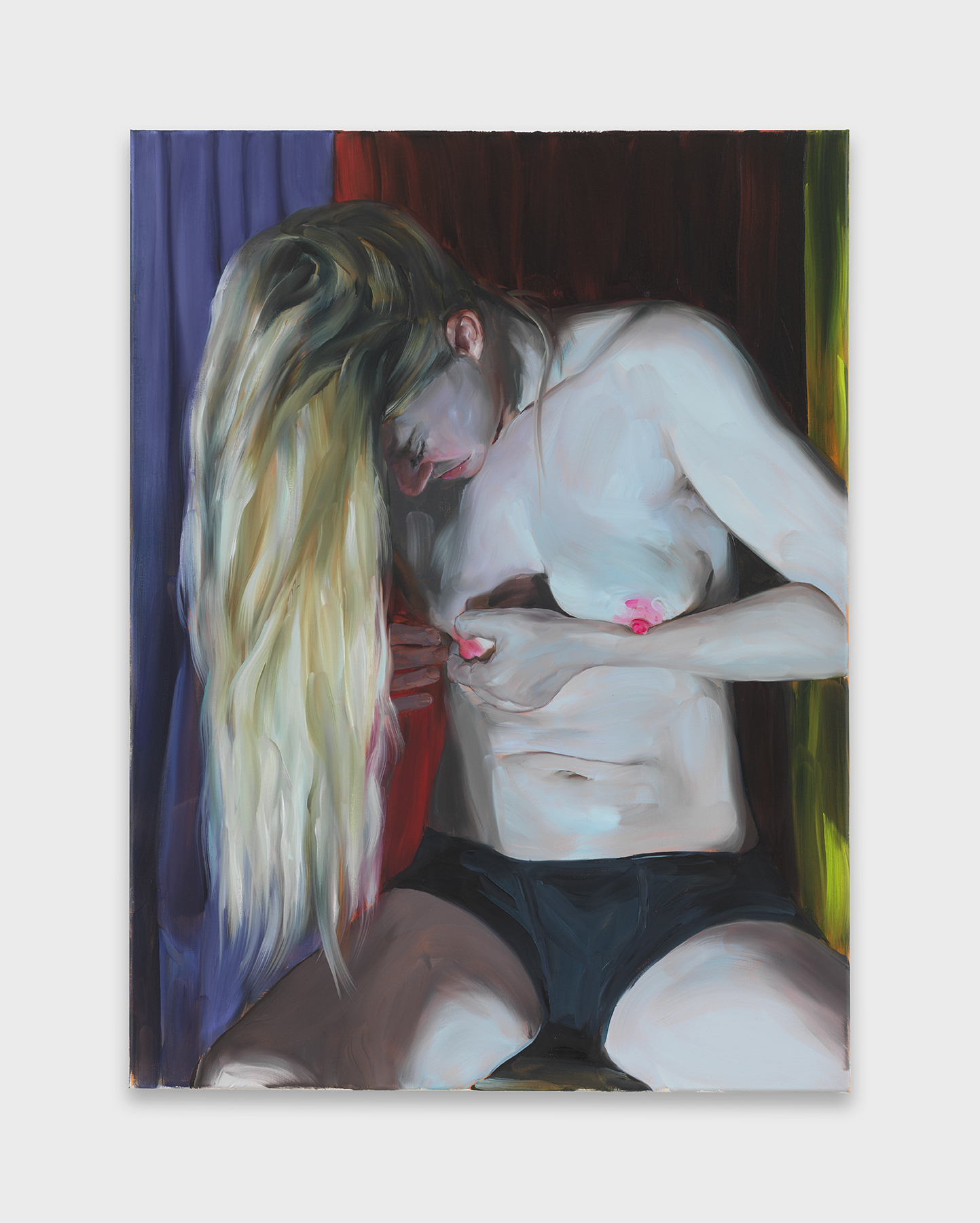

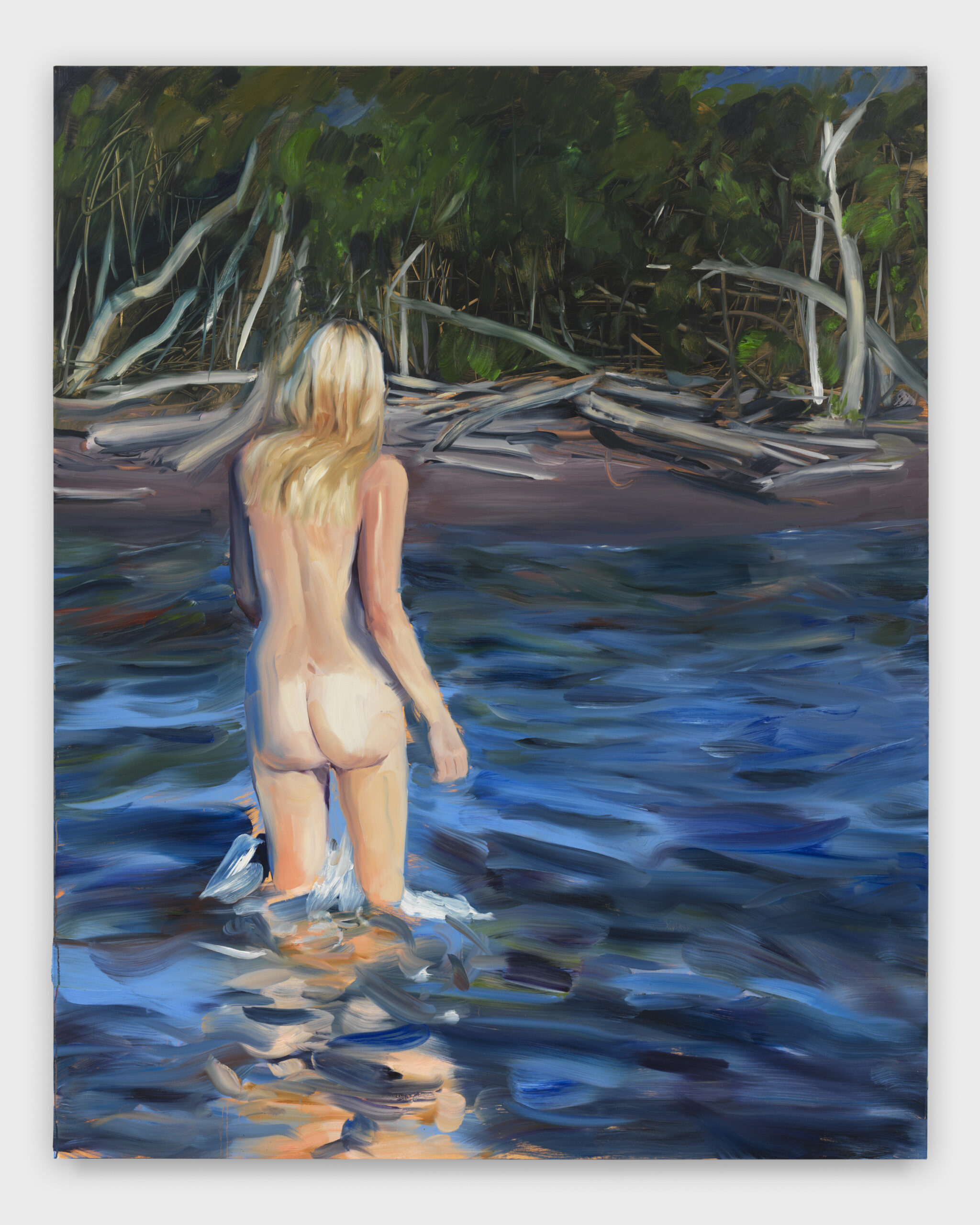

“I kind of have a thing for fingers” confessed Jenna Gribbon as she stood beneath a larger-than-life painting of her body with her wife Mackenzie Scott’s finger placed delicately on her pubes. The Honeymoon Show!, a collection of king-sized paintings (and a few intimate postcard-sized frames to boot) will adorn the glossy Lévy Gorvy Dayan townhouse until January 6, 2024. The show brings us along their Thailand honeymoon, Scott reaching into a coconut, or wading nude through water, and then transports us home from post-nuptial bliss to the curtain-clad studio space that Gribbon describes as something “between a circus and late-night show.” Over the course of the show, Gribbon unspools the pleasure of watching, of being seen, and the Venn diagram where fact and fiction overlap. Since they met six years ago, Gribbon has been painting Scott and evaluating notions of muse and subject, especially the absence of representations of women who desire women therein. “I’m so compelled to make them that I have to do it” said Gribbon when asked of her impulse to depict such private scenes. Basking in the post-show glow, the artist talked to us about painting female desire, lesbians of the 90s, and a fortuitous encounter with Richard Prince.

———

ELOISE KING-CLEMENTS: How are you doing post-show? Are you relieved?

JENNA GRIBBON: Yes, I’m always relieved when the paintings are finally on the wall and I can’t think about whether I should do something more to them. The opening was great, and it’s a relief to be on the other side. The next day, I fell down the stairs in my socks and kind of hurt my back, so I’m slightly injured, but other than that, I’m feeling great.

KING-CLEMENTS: Oh, no.

GRIBBON: I may have been moving a little too fast, so a little reminder to slow down.

KING-CLEMENTS: That’s good. Did you have a nice time at the opening?

GRIBBON: Yeah, I mean openings are super overwhelming. It’s a lot of talking to a lot of people, but I was actually really surprised to see so many people there. It’s such a big space that I thought that there would be no way for it to feel crowded. But actually, it was overwhelming but nice.

KING-CLEMENTS: That’s great. How long had you been preparing for this show?

GRIBBON: I think we started conversations maybe two years ago. Then I started thinking about the idea for the show around the time that Mackenzie and I got married, which was almost exactly a year ago.

KING-CLEMENTS: On your honeymoon, were you like, “This is going to be the show?”

GRIBBON: I wasn’t sure yet if I was going to make the leap to make the entire show about that. The idea of making a honeymoon show is almost repulsive in how saccharine the idea is. I’m not even a person who necessarily romanticized marriage. The idea feels very unlike me in a way, but it just felt like a really good vehicle for talking about some things I wanted to talk about in terms of public versus private, and real intimacy versus performed intimacy, and our collective desire to follow along and be a part of other people’s intimate moments.

KING-CLEMENTS: Do you ever feel protective over paintings, or have ones you don’t want to be sold?

GRIBBON: Occasionally, I do have that feeling. I am keeping one of the paintings from this show. If I had to pick a favorite, it’s probably the one that’s called I Am the Dog, which is the back of my dog’s head, really large in the foreground, looking at Mackenzie. The scene is zoomed out so you see the reality of the curtains, and the illusion is sort of dispelled and you see it’s just this room and the curtains are kind of paltry, and she’s standing there in a very unposed way, looking at the dog and the dog is looking at her. The dynamics of that painting are really doing what I wanted it to do.

KING-CLEMENTS: And how did this theme of being watched versus seen—and this scopophilic dance where you are embracing it but also pushing back against it—come about?

GRIBBON: My work has been dealing with that for the last, let’s say, six years. It comes from this internal conflict of wanting to paint women in this pleasurable way. I think it’s important for a woman who is romantically with women to be able to show that point of view. It’s also tricky as a woman who knows what it’s like to be objectified. The only way I knew how to do that was to sort of draw attention to all of the dynamics at play. For me, it’s really about helping the viewer empathize with the subject and thinking about how it feels to be the subject. To think about the position that we’re putting the subject in and what it means to consume an image of another person’s body. What is our part in that? What are we getting out of it? What does our participation mean? I love the history of painting, I love paintings of women, I love painting women and my life, but I wanted to do that in a way that was self-aware, and made the viewer self-aware.

KING-CLEMENTS: And why do you think it’s important for queer women to see that desire between other women?

GRIBBON: It’s important because we have so little of that kind of representation. I grew up without ever seeing that experience reflected back to me, and I think it’s part of the reason why it was so hard for me to understand myself. I’ve had so many women tell me how important it’s been for them to see these experiences portrayed. It’s part of the reason why I have to be fairly explicit about it. You almost have to hit people over the head for them to even understand what they’re looking at. And even though the paintings are what they are, and I put my own body in the paintings, you can tell that from the perspective that it’s me, and I’m with her, sometimes in a sexually explicit way. But people still have a hard time reading the paintings for what they are. They’ll do all kinds of mental gymnastics to see the paintings as anything but two women in a romantic or sexual relationship. So, until that’s not the case, I feel like I will be compelled to keep putting these images out there.

KING-CLEMENTS: Yeah, it’s like,”The surgeon is a woman.”

GRIBBON: Right, exactly.

KING-CLEMENTS: Do you remember your first experience seeing female desire for another woman portrayed in art?

GRIBBON: That is a good question. I mean, when I was growing up, the only lesbians I had ever heard of were Ellen DeGeneres or Rosie O’Donnell. I didn’t particularly identify with either of those people. I was a kid in the ’80s, and I don’t remember ever seeing any lesbian portrayals in the ’80s or even into the ’90s. As I grew up, I encountered quite a few gay men, but very few lesbians. There’s been a small explosion of representation very recently in TV and film, but I don’t really remember any early representations of it, to be honest.

KING-CLEMENTS: Yeah, it’s a shame. Your paintings are so intimate. I’m wondering if you’ve ever started a painting, and then you’re just like, “This is too much.”

GRIBBON: It does sometimes feel like jumping off a cliff, making some of these paintings. It’s almost like I’m so compelled to make them that I have to do it, even though I can’t believe that I’m making this painting. At the same time, I feel like it’s a painting that should exist in the world and no one else is going to make it if I don’t make it.

KING-CLEMENTS: Yes.

GRIBBON: So, I make the leap and I make these paintings, even though I’m actually, in real life, a sort of private person. It’s sort of funny that I’ve ended up making this work. I’m not actually comfortable being this person who makes these paintings.

KING-CLEMENTS: That is fascinating. To close, do you remember a milestone in the beginning of your career where you were like, “Oh, maybe I can make it as a painter.”

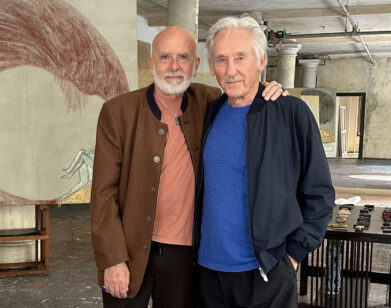

GRIBBON: There was a period of time where things were sort of happening in what felt like a very rapid succession. A really long period of my life felt like there was just silence. I was painting all that time and nothing was happening for me. It probably started happening about six years ago. I had a small show in my friend’s pop-up space in the East Village and somehow Richard Prince heard about the show and bought a bunch of work from it. That was really exciting. Really soon after that, I was looking at galleries, and I walked into Fredericks & Freiser, and Andy [Freiser] looked at me and he was like, “Oh, you’re Jenna Gribbon, aren’t you? I’ve been meaning to email you, to ask you to be in the show.” I was floored. I had never walked into a gallery and been recognized or addressed at all. For so long I felt like this completely invisible artist that made paintings that nobody cared about. That was really encouraging, and things really started to unfold pretty quickly from there. I never thought things could get to where they are. My great hope was to afford a studio and maybe not have a day job. But the response to the work has been, honestly, more than I ever dreamed it would be.

KING-CLEMENTS: Thank you for this. I really, really appreciate your time.

GRIBBON: Yeah, sure. Thank you.