OPENING

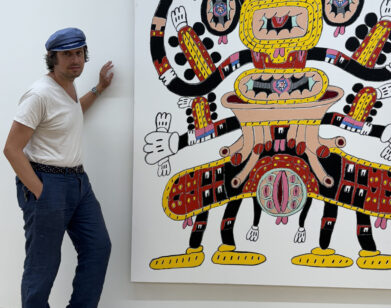

Painter Emily Coan on Fairytales, Femininity and Tradwife Tiktok

Painter Emily Coan has quite an elaborate way of constructing a reference for a painting. For her latest show Spider Silk, which opened at DIMIN last week, she gathered a group of young artists and creatives at a discreet location in the Hudson Valley and asked them to act out a fairy tale she devised, in which the girls are working together to create garments—or, rather, armor, out of spider silk. “It’s about trying to embrace more feminine values of collaboration and working together to better the group,” Coan told me a couple of weeks before her show opened. When we met at the gallery, I learn that the story was inspired in large part by Coan’s experiences growing up in Florida in the world of debutantes and cheerleading, where certain articles of clothing denote stereotypically feminine roles. Naturally, we got to talking about pageantry, female sensuality, and tradwife TikTok.

———

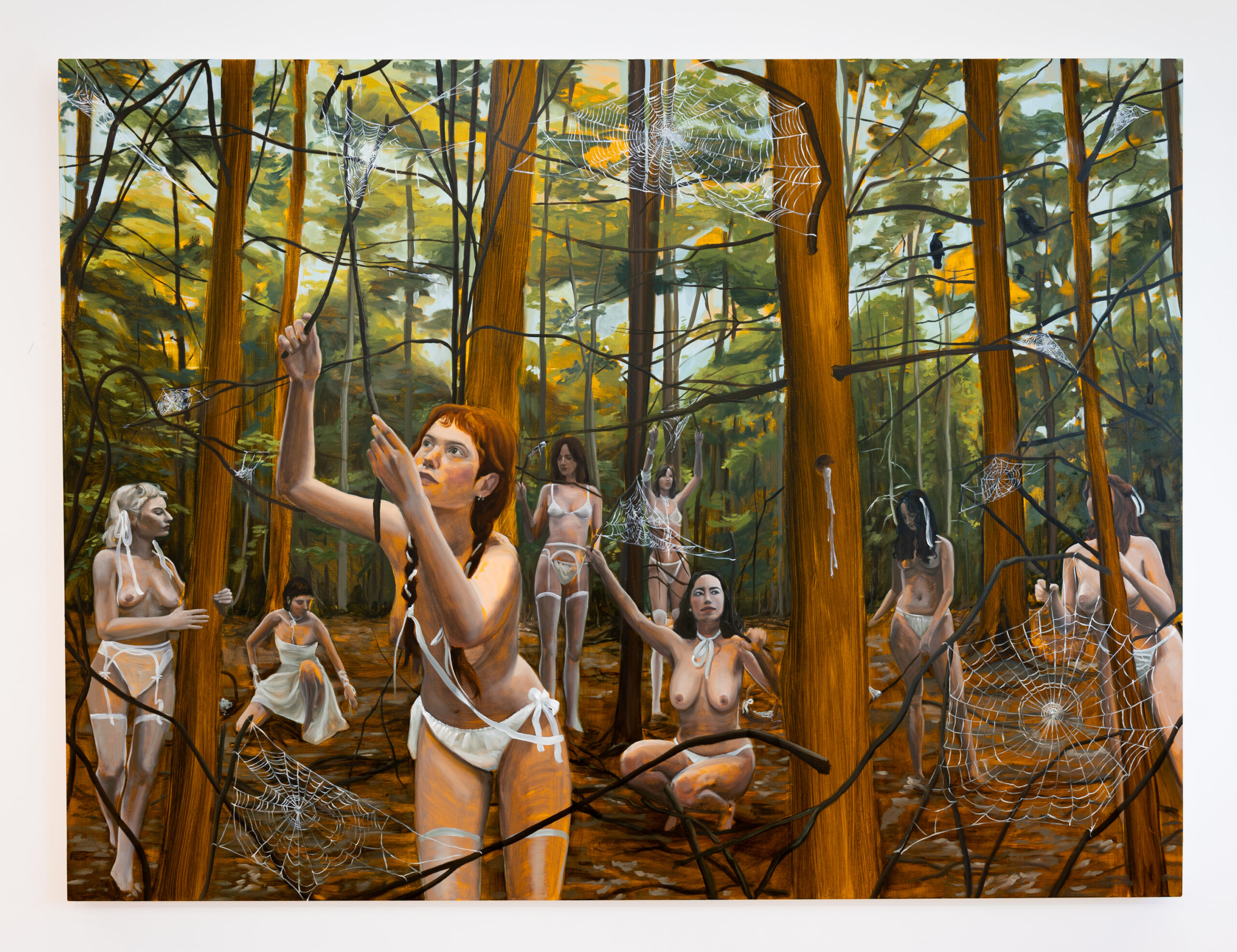

EMILY COAN: So the story I had the models play in is called Spider Silk. It’s a group of eight sisters in the fairytale realm. They have to find and collect spiderwebs and then weave it into garments that will help them transcend to the next realm. These girls are all artists and creative people. They’re friends in the Hudson Valley where I live. We shot on the summer solstice last year, and you’ll find traces of the story in each painting. And throughout, they’re in various stages of making the clothes and being more or less dressed. And spider silk is stronger than steel, so–

EMILY SANDSTROM: Really?

COAN: Yeah.

SANDSTROM: Wow. There’s no way I’m the only person who doesn’t know this. Why don’t we harvest silk from spiders more?

COAN: It’s really hard to make and it’s super expensive. There’s only two garments that have been made from it.

SANDSTROM: Does it take them a really long time to produce?

COAN: Yeah. They hold the spider down and pull the tiny little thread out.

SANDSTROM: Oh.

COAN: Yeah.

SANDSTROM: How did you become interested in that?

COAN: Sometimes stuff just bubbles up in the collective unconscious. I was hearing about spider silk a lot, and also I’m reading a book right now with spider silk in it, and I have a friend who had a song called “Spider Silk” that came out right after I shot this. But I’ve always been interested in clothing and garments as protection. Feminine, beautiful things as a source of power and protection.

SANDSTROM: Is it translucent?

COAN: It’s actually kind of yellow, so I took some creative liberties.

SANDSTROM: I see. Can you tell me about the white garments and what role they play here?

Gathering Webs for Spider Silk, 2024 Oil on linen. 60 x 80 in. Courtesy of the artist and DIMIN.

COAN: I was working with a different story for a really long time about the descent into the underworld. For years, it was like these innocent women go into the underworld and they’re exposed to all of this horror and then they have to come back up. They wear their clothes of innocence as a means to power, even though they’re wiser. The white is important, and I’m not sure that I can articulate it. It’s just so loaded. I’ve always been really interested in wedding lingerie because it seems so weird.

SANDSTROM: It is weird.

COAN: Yeah. It’s like an oxymoron.

SANDSTROM: Are the ribbons a deliberate compliment to the lingerie?

COAN: Definitely. I was wearing a lot of this stuff growing up because I was a debutante.

SANDSTROM: Wow.

COAN: And I was a cheerleader. So situations where there’s power and social status based off of feminine roles, and with specific garments that go with it, are really important to my personal cosmology.

SANDSTROM: Absolutely. Tell me about being a debutante, because that’s a really interesting lens through which to view these paintings.

COAN: I’m from Florida, so it’s a different social strata than the debutantes here, but it’s community leaders coming together and it’s very ritualized. All the men wear suits with tails and gloves and we had to get wedding gowns that were white, white, white. Like, blue white, and nothing else was acceptable. You’re supposed to be introduced into society as daughters of powerful men in the area, which for me was really weird because that’s my stepdad. My mom married into that, and things changed a lot after. My mom was living through me because she grew up in St. Petersburg, Florida and was way lower class. She leveled up a lot with this marriage to her high school best friend after their 20-year reunion.

SANDSTROM: How old were you at that time?

COAN: I was nine, and it was during the Bush and Gore election in Florida. My mom was a staunch democrat, and then she totally shut up when we moved in with my stepdad. He was really Republican.

SANDSTROM: Are your paintings almost a riposte to your upbringing?

COAN: It’s more about the experience of being really aware of femininity as a source of power of growing up and how that has informed the way that I make the work and the symbols therein. I don’t feel like I’m directly tackling anything like that. I love the pageantry of all of those things, and power is something that I’ve been interested in for a long time. But that’s shifting with this body of work, where instead of it being about individual power, it’s about trying to embrace more feminine values of collaboration and working together to better the group.

SANDSTROM: That’s a great segue because I wanted to get into how you decided to set up the scene. It’s like role-play or theater, constructing something live to then taking still images to paint it. Where did the idea come from?

COAN: For the last few years, I’ve been really focused on what comes out in my brain. I sketch it and compose it beforehand. But for this, I really felt like I understand composition now, and I started using photo references again so that I don’t have to overwork things for not being sure of where an arm is or something. But this process was so fun. They all got all dressed up and I could tell that they weren’t sure about the outfits at first. This was one of the first setups that we did. They’re all standing in this light and looking at each other and then they’re like, “We get the story.” So, I directed them. I was pretty loose with it. I was like, “I want you guys to just play, and I need foreground, middle ground, and background, and I need you all to keep moving. I don’t want you to pose, I want you to interact.” The best compositions were more organic. I have folders of images and I’ll take elements from five or six photos, but usually it’s one composition that I like. That’s the anchor.

SANDSTROM: By the time you were wrapping up, were the girls really living out the fairy tale?

COAN: Yeah. It makes me want to cry thinking about it because it was so special.

SANDSTROM: Because there’s such a live action component, I can’t help but ask: did you consider a video or a play instead of or in addition to the paintings?

COAN: I just got chills because I would love to do that. I studied sculpture in school and I was making installation video art. This really feels like I’m doing the same thing. I made a short film with a friend in 2012. I spent a whole summer on it, then he decided not to release it and it’s never seen the light of day. I realized that, in collaborations, I have to endure these hiccups and roadblocks and I would rather just do everything myself. I don’t know if that’s a good answer, but I really like being alone and being in the studio by myself.

Our Lady, 2024 Oil on linen. 60 x 72 in. Courtesy of the artist and DIMIN.

SANDSTROM: Yeah, there is a more solitary component.

COAN: Right, because when you’re making a film, there’s so many elements that go into it. But I did feel really comfortable being a director and directing this shoot.

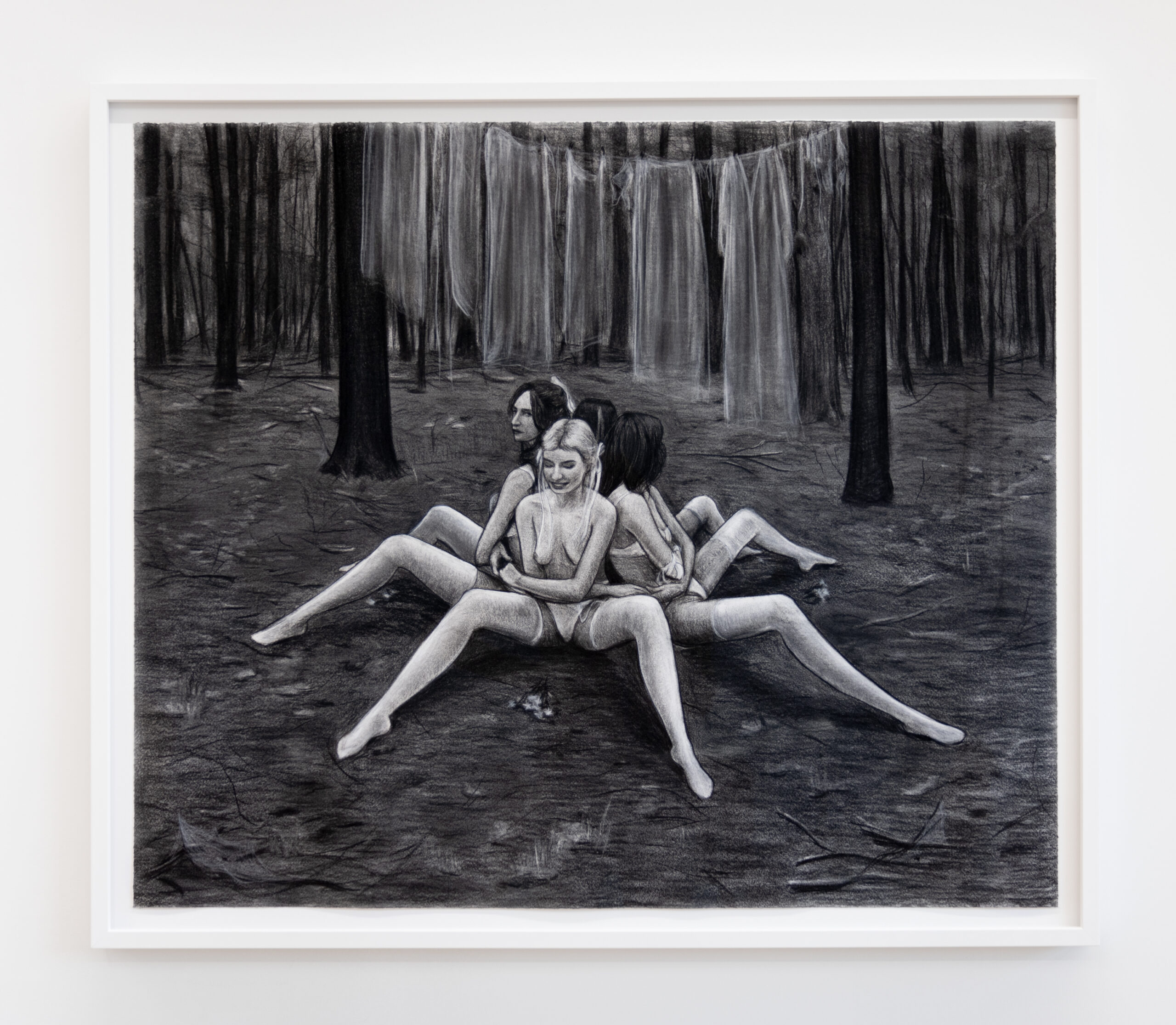

SANDSTROM: That translates very much. I want to talk about myths and fairy tales. In the story, the girls are harvesting spider silk to build their own clothing, symbolizing a feminine armor. What are they protecting themselves against?

COAN: Protection from outside forces and inside forces. It’s not fully fleshed out as a story, but the idea was they need to create these garments out of love for each other to be able to transcend into the next realm. I wanted to ask, “What’s it like to not be in strict competition with other women?” What’s it like to be collaborative and to have a generative relationship that’s outside of how we’ve been brought up in America? I’ve been experimenting with leaning more into my femininity, and that’s definitely part of this.

SANDSTROM: What usually deters you from your femininity? Or what do you not like about being a woman?

COAN: I have contradictory feelings about it, because I loved being in my twenties and showing up with this intense sexual energy and being seductive. But then you find that men don’t take you seriously as anything else other than a sex object. I’ve wanted to be the sex object, and I’ve also wanted to be the artist. The muse, and the artist.

SANDSTROM: Are you married?

COAN: Yeah. He’s the only person my hyper-sexuality didn’t work on at all.

SANDSTROM: Oh, so he’s really the one.

COAN: Yeah. Since getting married a year-and-a-half ago, he’s been trying to take on more masculine roles, and I’m trying to soften into my femininity. I was so haggard before, and I wasn’t aware of that.

SANDSTROM: Is that what everyone calls trad?

COAN: Yeah. We’re not trad, though. I’m so fascinated by trad wives, though. I’m on trad wife and trad wife discourse TikTok.

SANDSTROM: I love that shit. I’m stuck in Nara Smith’s world.

COAN: Yeah. I wasn’t really exposed to Mormon culture before TikTok, but the garments, I’m fascinated by them like, “What is that?”

SANDSTROM: Yeah. There’s a lot of overlap there with your work and symbolic garment wearing.

COAN: The thing about trad wives that has landed with me is that, throughout history, a lot of technologies have evolved to make women’s lives easier, but then the standard is raised with every intervention. You can’t just make a sheet cake anymore. You have to make it really beautiful, and pipe it out, and it has to be on social media. Women’s work is constantly being elevated. We’re always striving for more excellence with each intervention that we get through technology. That’s what’s interesting about Nara Smith. She’s going to make her kids peanut butter and jelly from scratch. It’s so unnecessary. But if you have a nanny and you’re born and bred to be a wife, then you have to fill your day with something.

SANDSTROM: Yeah. I mean, if I liked kids and cooking that much, then why not? But one last thing I wanted to ask about your paintings. Sometimes, when I look at imagery like this, there is something sexual about it. Obviously, this is a story about care and trust, and this isn’t pornographic, but do you ever see your work through that lens?

COAN: Yeah. It’s confusing, sexual and sensual are often wrapped up in each other. But in this culture, it’s always sexual or it’s always pure. I’m glad that this is bringing up something for you because, to me, this work shouldn’t be controversial. But it’s censored. Depicting feminine sensuality and pleasure is hard. We’re discouraged from those sensual feelings of pleasure, too. It’s written off as unimportant or indulgent. But I think part of what I’ve learned from my husband is that he’s very sensual, and life is sensual.

Eight-Legged Ritual, 2023 Charcoal on paper, framed 32 1⁄4 x 37 3⁄4 in. Courtesy of the artist and DIMIN.