Nobody Knows the Trouble His Nose Has Seen

PHOTO COURTESY KEN HOWARD/METROPOLITAN OPERA

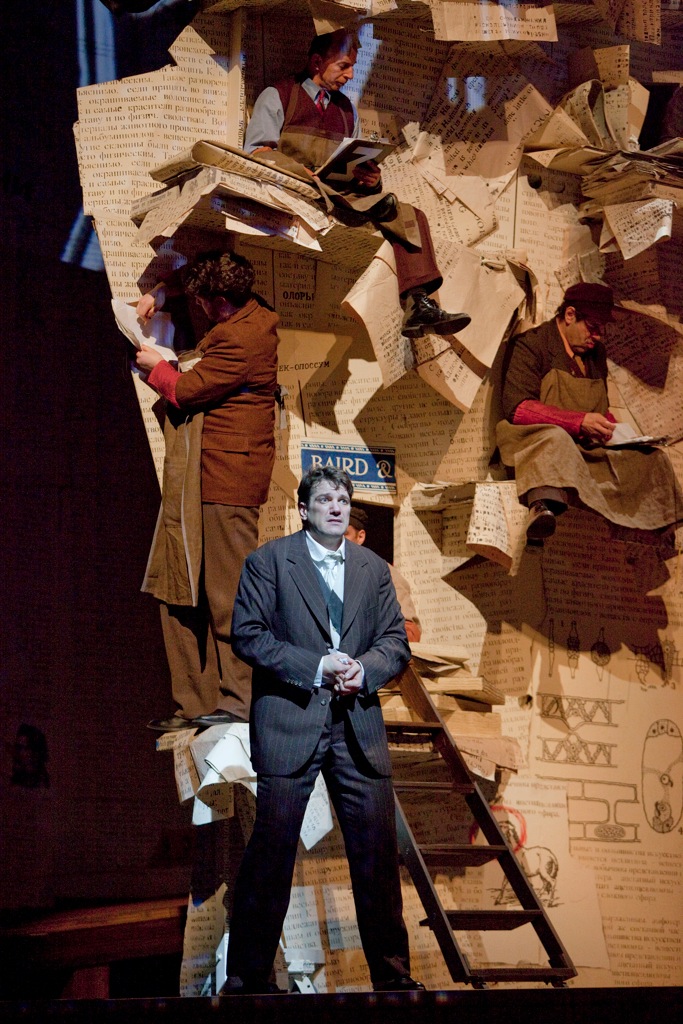

If the cast had missed curtain call at Friday’s opening night of “The Nose” at The Metropolitan Opera, the audience might not have noticed with all the twirling and unfolding of the sets. And that’s not a negative of the review of the level of performance, although the sets gave them a lot to live up to—or compete with. After all, the reason that the center section of the Met was filled with art worlders like Marian Goodman, Maurizio Cattelan, and Robert Storr was that South African artist William Kentridge had completed sets and projections that were characters in and of themselves. Embarking on a six-performance run, Kentridge directs this rarely performed opera from Dmitri Shostakovich, whose libretto was taken from a short story by the Nineteenth Century Ukrainian satirist Nikolai Gogol.

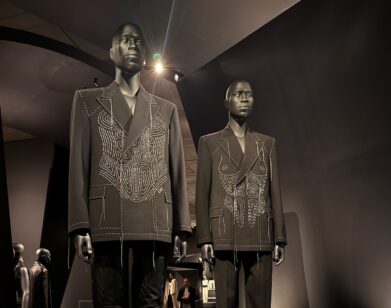

The story is simple, even as operas go: A low-level Russian official wakes up one morning to find that his nose is missing, having absconded with any sense of reason running around town in the uniform of a decorated councilor. The lead, played smartly by Baritone Paulo Szot, bumbles around mid-nineteenth century St. Petersburg trying to make sense of his situation while navigating the society’s labyrinthine bureaucracy. The Nose, represented in various forms but most humorously as a giant dancing papier-mâché schnoz with legs, rejects any obligation and answers to his former keeper rhetorically.

Kentridge’s stage set is grounded by a soaring background scrim of collaged images and texts that recall a pastiche interpretation of Dada and Russian Constructivism: maxims rendered in various languages regurgitated from the Gogol or invented by Kentridge himself. There’s a feeling that the entire performance is being recounted on the broadsheet of an early Soviet-era newspaper with rooms, ramps and characters emerging from within. Projected animations of even more texts dance around Futurist-inspired shape collages that are syncopated with the discordant music among images of the nose rollicking around the streets like a tyrant.

These jittery cartoons are both distractions and lubrications to the story’s minimal plot which is rife with absurdist tangents as well as Shostakovich’s jarring assemblage of musical styles. Soaring solos terminate sharply with staccato choral interludes, which then segue into quaint folk ballads or spoken lines. Slapstick humor helps, too.

Shostakovich’s opera is so rarely performed because it’s a work that requires focus to appreciate the score’s hijinks and intimacy to inhabit the characters’ unpredictable intentions. Another reason is that the Nose premiered during the early days of the Soviet Union, and was not reviewed kindly. A majority of the composer’s creative life was stifled by the Stalinist regime. The same was true for Gogol who felt unable to assert his Ukrainian identity in the region’s troubled 19th Century and lived as an ascetic. It’s no surprise that Kentridge, whose artwork has deep connections to his home nation of South Africa, was drawn to the obscure story. His works, be they performed, animated or on paper, are about fractured nationhood, psychological projection and identity having grown up a colonist and having lived through the nation’s apartheid. Theorist Walter Benjamin said it best when he claimed that you couldn’t know a city until you got lost in it. And here, too, a map seems superfluous.