New Again: Roy Lichtenstein

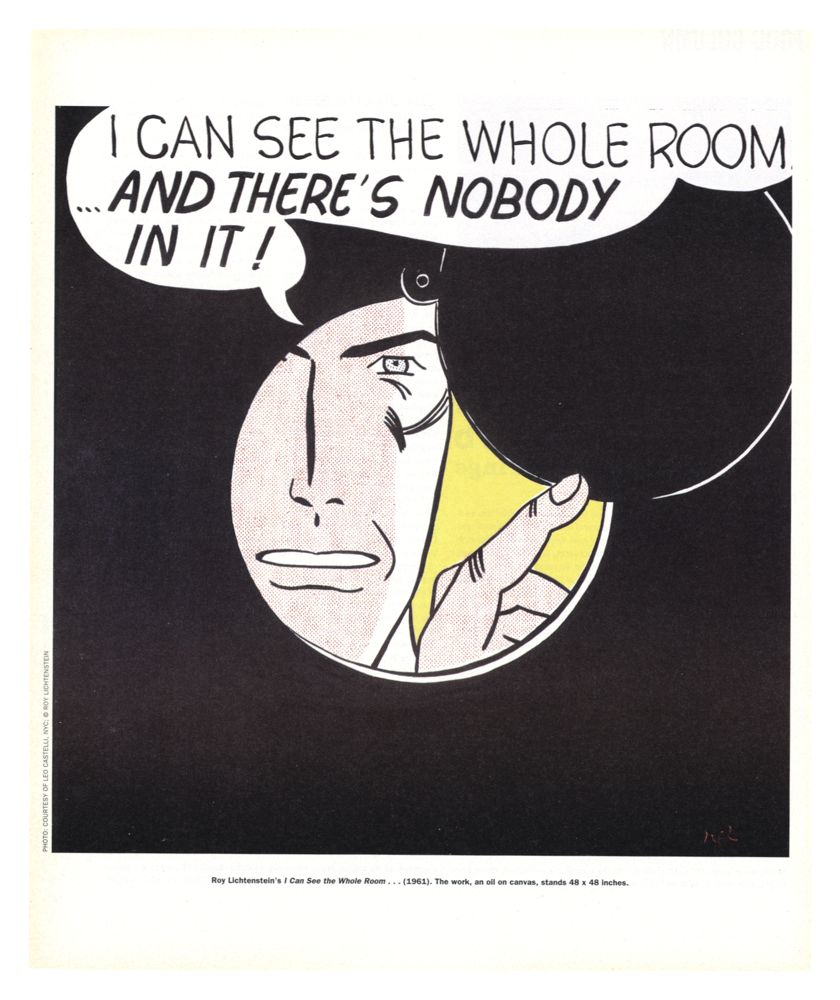

ABOVE: ROY LICHTENSTEIN, I CAN SEE THE WHOLE ROOM. . ., (1961). OIL ON CANVAS, 48 IN. X 48 IN.

Much like our founder Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein should be too popular, too ubiquitous, to remain a name to drop. Who isn’t familiar with Lichtenstein’s “Drowning Girl” (1963) or “Whaam!” (1963)? So you like “Crying Girl”? Get in line.

Somehow, however, Lichtenstein has evaded this curse of the cliché. Even two decades after his death, Lichtenstein’s bright, bold pop-art appeals to art enthusiasts and laypeople alike, the perfect mix of retro kitsch and oh-so-modern irony.

In memory of the artist, who died 15 years ago this Saturday, we’ve reprinted an interview between Lichtenstein and David Bowie (another adored, yet still captivating, pop icon) from our January 1998 issue.

Crash! Bang! Boom! It’s Roy!

By David Bowie

Shortly before his death, artist Roy Lichtenstein had a lively conversation about his work with David Bowie. When the two met, things were bound to go “pop”—and they did.

DAVID BOWIE: When you make a painting or a sculpture, do you find that the finished work often contains information you hadn’t intended?

ROY LICHTENSTEIN: Oh yeah. I think there’s no doubt about it. But usually I begin things through a drawing, so a lot of things are worked out in the drawing. But even then, I still allow for and want to make changes.

BOWIE: Through the medium itself?

LICHTENSTEIN: Well, possibly. For instance the color is different, you know, from just colored pencil to colored paint—it’s two different things. I kind of do the drawing with the painting in mind, but it’s very hard to guess at a size or a color and the colors around it and what it will really look like. It’s only a guess at the beginning, and then I try to refine it. My things seem to be very exacting, but they’re really not done that way. I allow for a lot of latitude. I want the look very blatant, and to come on in a strong way, but you want to let the painting simply be unresolved in order to do this.

BOWIE: I know exactly what you mean. I find this in music as well. All the time.

LICHTENSTEIN: Yeah, you know, you like it to come on like gangbusters, but you get into passages that are very interesting and subtle, and sometimes your original intent changes quite a bit.

BOWIE: Here’s a question: Why do you feel that a romantic or emotional situation needs to be represented mechanically?

LICHTENSTEIN: Well, I think that has a lot to do with all kinds of things presented through the media in the modern day. I mean, it’s even in movies—you know, two people are about to kiss, and in reality you’ve got a guy at the camera with a cigar in his mouth, [chuckles] and there’s probably a stylist who’s just powdered their noses. The actors have to pretend that they’re amorous in this situation, [chuckles] while there are all these technical people involved. That’s an example that just comes to mind immediately.

BOWIE: You still seem to ponder the symbols that are represented in the romantic or emotional situation. You’re still very much a man of irony. When you first started, you picked on Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck. Were they arbitrary choices, or did you feel there was some inherent information in those two?

LICHTENSTEIN: They were so far from serious abstract expressionism that they embodied everything. They were done mechanically, but they represent something everybody loves. A number of artists have done things with Mickey Mouse—including Oldenburg and Warhol. He’s such an American symbol, and such an anti-art symbol.

BOWIE: Does the general public know when it’s looking at art?

LICHTENSTEIN: It’s hard to know. [laughs] I’m sure some people do and some don’t, but you get so far away from the general public in any of these fields. You know, as you compose music, you’re just off in your own world. You have no idea where reality is, so to have an idea of what people think is pretty hard.

BOWIE: As a society, are we generally smart at picking up information from art?

LICHTENSTEIN: I think we’re much smarter than we were. Everybody knows that abstract art can be art, and most people understand there’s another purpose to it. I think that most people think painters are kind of ridiculous, you know? [laughs] I think that they think the same of modern composers.

BOWIE: It’s interesting how I find that myself. My work is really the accumulation of these different moods that I’ve had throughout my life and where they’ve taken me. I start looking back, and I think, I’ve actually created a life out of all this, out of these changes of mood. They’ve pushed me through all these years, and I seem to have a semblance of a life, and if I look very carefully, I can see some thematic design to it. There’s some continuity.

LICHTENSTEIN: You’ve created a world than even other people can see.

BOWIE: Yes. But to go back again to your earlier days, I wanted to ask you about the effect in the ‘50s and ‘60s of people like, say, Edward Keinholz or Joseph Beuys or the Fluxus movement or Bruce Nauman. Were you affected by what they were doing?

LICHTENSTEIN: I was at Rutgers University, and that was a center for Fluxus in a way. But it wasn’t what I was interested in. All of it had an impact—as did happenings—because I could see that art was changing from expressionism, which I was doing at the time, or thought I was doing. [laughs] But it wasn’t the direction I really wanted to go.

BOWIE: Did it, in fact, push you further in the direction you were going?

LICHTENSTEIN: Maybe, because my direction is very anti-contemplative. If you thought I was for these commercial products, you’d think there was no irony. The irony isn’t meant to be an ironic comment on our society, exactly. I just felt that these kinds of images are big; it’s what people really see. We’re not living in a school-of-Paris world, you know, and the things we really see in America are like this. It’s McDonald’s, it’s not Le Corbusier. But the thing is, I’ve been saying the same thing over and over for 35 years. [laughs]

BOWIE: Your latest work shows a yearning, possibly, for something more contemplative. The Chinese landscapes you were working on when I first met you are quite the reverse of what you were just saying about your earlier work. You seem to yearning for something more serene at the moment.

LICHTENSTEIN: I like it to appear to be serene, but also to be pseudoserene. [laughs]

This interview is excerpted from RayGun: Out of Control, published by Booth-Clibborn Editions.

THIS INTERVIEW INTIALLY APPEARED IN THE JANUARY 1998 EDITION OF INTERVIEW.

For more New Again, click here.