The MoMA Armory Party: Sculptures, Tequila, and a Rhinestone Cowboy

“Going Out” is a column celebrating the legacy of our founder, Andy Warhol. Long ago, in the disco ball-refracted days of The Factory, Warhol’s Interview chronicled the comings and goings of the downtown scene, spotlighting its ever-eccentric populace in their favorite dimly-lit haunts. In this edition, Ernest Macias and Mark Alan Burger giddy-up to midtown for modern art and Orville Peck. Yeehaw!

Around the dead of night last Wednesday at the MoMA, Donald Trump was handing out copies of his Social Security card. Passersby commented on works by Dorothea Lange and Jeff Koons as “Can’t Get You Out of My Head” by Kylie Minogue pulsed in the background. A cohort of partygoers fawned over a tiny, trembling white dog in the clutches of its owner. A masked singer, in a teal, bejeweled suit, sang about buffalos and drag queens. The MoMA’s annual Armory Party—part art show, part concert, part Lynchian meta-commentary—was in full swing.

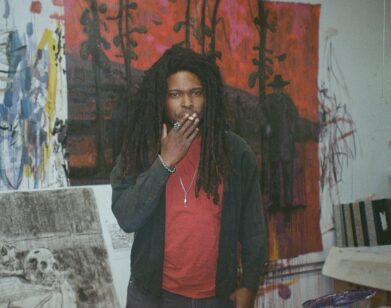

Everything was—and wasn’t—as it seemed. In reality, “Trump” was tootsie warhol, an impersonator posing for oglers. The Koons was real, though, as was the dog, which remained perched in its owner’s arms as she wandered through the second floor galleries. Near the makeshift stage in the center of the museum’s lobby, the audience bounced in eclectic rhythm to Sister Nancy and Empire of the Sun. “Nobody’s dancing,” announced the artist Kambui Olujimi, who, as he made his way down the North staircase, made up for the apparent lack with a two-step of his own. Olujimi’s outfit—a shirt and pants with dizzying, clashing prints—helped him to stand out in the crowd, which by and large consisted of formal and formal-adjacent wear. There were, however, moments of revelation: a thick, yak-like vest, a white leather harness over a blue button-down shirt, a distressed Marilyn Manson t-shirt, and a fireman’s coat tailored with yellow reflective lining, along with several cowboy hats, boots, and embroidered shirts. After all, the masked country singer Orville Peck would be making an appearance later that night, whose performance was teased by hazy screens glowing in the lobby.

As Peck and his band took to the stage, the fervor of the crowd began to coalesce: some front-row onlookers with bare, tattooed arms and leather skirts, knew all the words, and threw up the sign of the horns with one hand as the other clutched a tequila soda; some, standing further back, seemed delightfully perplexed by the rhinestoned cowboy: “I have no idea who he is, but everyone’s going crazy over him,” snarked some partygoer making his way through the crowd; others still meandered around the bars, bemoaning the inevitable late-night ride back to Brooklyn.

Peck ran through several tracks from his album, including a new one with a hook that sent the words “summertime” echoing through the halls, reaching the selfie-takers exploring Haegue Yang’s glitter-like covered sculptures from the exhibit Handles. The MoMA closed last year to expand its terf and evaluate its permanent collection (which they claim will highlight more works by women, Black, and Latinx artists). This year’s Armory Party showcased a bigger, bolder, and purportedly more inclusive MoMA, one that’s primed for all kinds of patrons who are looking to expand their artistic vocabulary—or two-step in cowboy boots in between two Richard Serra sculptures.