Mira Calix Cascades

For those not acquainted with Sydney’s contemporary multi-arts center Carriageworks, the simplest visual is a series of cavernous halls, all exposed brick and polished concrete. Though stripped of its former industrial equipment (tools for blacksmiths and railway carriage workshops), the now heritage-listed spaces retain a feeling of weightiness.

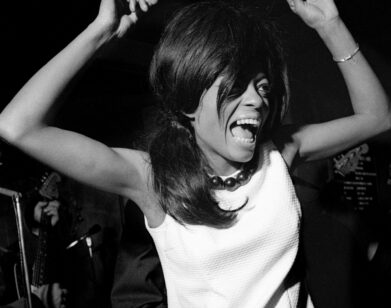

In mid-December, installation and sculptural artist Mira Calix–whose given name is Chantal Francesca Passamonte–met us in an adjoining bar between periods of working on an upcoming immersive installation. The South African-born, U.K.-based artist was in town for a short spell, conducting interviews and fine-tuning the logistics of her new participatory installation, Inside There Falls, ahead of its 2015 Sydney Festival debut as part of the Sound / On Sound program. Inside There Falls is an ambitious commission, in terms of both physical scale and its fusion of music, voice, and dance.

As an artist, Calix is unfazed by glittering commercialism, and while her installations and performances are immersive and physically overwhelming, they’re also unabashedly peculiar. She previously set Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 130“ to music for The Royal Shakespeare Company, integrated the recorded sounds of insects to electronic soundscapes (specifically, larvae hatching, wasps and flies moving, and butterflies frantically beating their wings), and united esteemed orchestras with live crickets and cicadas. Calix first made a name for herself as an electronic musician, releasing five albums via Warp Records, and although she continues this musical pursuit, she now focuses on the intersection of sound and art.

Inside There Falls debuts on January 8, and for more than a week, an entire bay of Carriageworks will be transformed into a sensory paper labyrinth, complete with tumbling paper streams, an elusive voice track, and movements choreographed by Rafael Bonachela of the Sydney Dance Company. Calix describes the interactive set as a milky, white mesh, punctuated by violet blues and deep oranges, an open-ended encounter with language, fragile architecture, and the human form. “The physical work feels like a cascade,” she says. “Everything is falling.”

LAURA BANNISTER: You’re a long way from home. Do you like being in transit?

MIRA CALIX: I don’t mind flying at all. But this flight–London to Australia–it’s just so damn long! I find flying interesting in that it’s a very intimate experience. You’re so close, physically, to one or two other people and you eat, sleep, do everything together. I’ve met the most extraordinary people on planes, some of whom I’ve stayed in touch with, some I haven’t. Even if you’re beside someone who ignores you for eight hours, there’s a physicality you wouldn’t put up with from anyone other than someone you knew well. You’re in it together, even if you never say a word to one another. I once got on a plane and sat next to a fireman and we laughed all the way to L.A.–11 hours and I have no idea why! His wife was two sections away and could hear him bellowing. She couldn’t figure out what the hell was so funny.

BANNISTER: It’s a strange intimacy, isn’t it? You can’t disembark like you would on a train. You’re just suspended in the sky with a group of strangers.

CALIX: It’s a weird bubble. It’s fascinating. And you have no choice but to endure it. You’re only alone in the loo. Sometimes I go to the loo just to be alone. Anyway, I wrote this piece of music that’s exactly about all this in-flight experience, a field-recording project. It’s called “Meeting You Seemed Easy.” I put a sound recorder in my handbag, took it through immigration and onto the plane. Through a weird accident–well, a delay–I ended up going to sit with the pilot. Video was illegal, but they let me record everything in the cockpit. They later came to the concert. I’ve got this lovely recording of the pilot explaining all the buttons to me; each has a shape that reflects what the button does. It taps into cognitive memory, so that even at your most subconscious or panicked state, the things you’re pressing reflect what you’re doing. It’s like play-doh or Lego.

BANNISTER: Technology is essential to your compositions. Do you often tape your observations? I must admit I’ve done it myself at real estate auctions. The auctioneers are so slimy. Real showmen.

CALIX: I do a lot of field recordings. Mostly I’m recording organic matter, like insects [and] crickets. Your auctioneer example is interesting. They have a sort of pattern when they talk. It’s so musical–going once, going twice. You’ve got a piece there! You could call it “Houses I Didn’t Buy.”

BANNISTER: Let’s talk about Inside There Falls. In the description I’ve seen, it seems as though it emerged from an email sent to you by a stranger. Was it really as romantic as that?

CALIX: It was very simple and began in 2011. The email said “I’d like to share something with you.” It came in the middle of the night, the person was based in Australia, but I happened to be awake and replied right away. I said they could send me whatever they needed to.

Their document described a dream. It came with no explanation or context, but I remember reading it and finding a lot of words I really resonated with, words I liked the sound of. I was working on a stone sculpture at the time, and didn’t give the email much thought, but it stuck with me and planted itself in the back of my head. At some point it became clear to me that [this should become a work]. The original text is much longer, around 30 pages, but there’s an extract that accompanies the piece.

What interested me wasn’t the content of this text, but the impression it left on me. I think that when we read an article, or a story, it stays and resonates with us because we find something of ourselves in the work. That’s the only reason it sticks. You remember the text in a way it was probably never told. This is what Inside There Falls is. The audience will come and inadvertently create new, personal stories. I’m giving them abstractions, all the components of a story, and I’m saying, “Come, make your story.”

BANNISTER: What components of a story are you providing? Is it as simple as setting, movement, and sound?

CALIX: Yes. I’m architecturally building what I consider to be a narrative. The work uses many plot devices in the true sense of an opera, if you want to think of it that way. I’m using every medium that I think suits it … The audience will step into this narrative and put it together, depending on where they enter, how the sound is moving past them, [and] which elements they pick up. I’m starting to sound like a slightly absurd person, but it makes sense to me. My work is always exploring what happens in the space between the creator and the receiver. Willingly or unwillingly, the receiver is also a creator. They’re a creator when responding to any work of art, but I just happen to be teasing that out more.

BANNISTER: Do you know anything else about the person who sent you the text? Are they aware it has been repurposed?

CALIX: Yes, we’ve met and he knows about the work. He’s just lovely. But everything about it is strange! He knew of my music and my work. He didn’t know why he decided to contact me; he just felt like he should. He’d never done anything like that before. He’d actually written the piece over a decade ago and it had been stuck on a floppy disc.

BANNISTER: How big is Inside There Falls, physically?

CALIX: It’s the whole of Carriageworks’s Bay 17.

BANNISTER: Can you give me some sense of it? How will Bonachela’s dancers move through the space?

CALIX: They come in and out, unannounced, though they are choreographed. To me they’re another device, another sculptural element, just like the paper. Their purpose in this work is to be part of it. You may or may not see the dancers when you visit–if you stick around long enough you will. The work plays out no matter what and audiences are completely free to move around within it.

BANNISTER: Site-specificity is obviously important to you, but I’m interested to know if location on a broader level is significant too. Would this work be different if it was staged in Berlin or New York?

CALIX: I think the work would appear the same anywhere, but the elements are always unique. I folded each piece of paper with five amazing assistants, [so] what will be different are the people, the audience. Also, time changes things. The piece is falling apart. It’s degrading. Day one will be different than day 10.

BANNISTER: Much of the work derives from natural fibers, but technology has a role too. How do the two unite in your mind?

CALIX: When I was doing mainly music, I used to stick a microphone out the window, into the countryside, and create a live mix. I wanted to put air in electronic music. I record the sounds of twigs, barks, and stones. I’ve always been obsessed with the idea of combining the natural and the man-made. It’s not because I think the technology is crap, or [that I’m] trying to work against it, but that juxtaposition is truly beautiful. The question of what is natural and unnatural is very open.

BANNISTER: There’s a recent interview on ArtForum that relates to what you’re saying. It’s a conversation between critic Paul Galves and Michel Serres. There’s a point where Serres says the realms of nature and information aren’t opposed. He says we don’t have to view things as nature versus organic, they can coexist in a very chaotic way, that they’re liquid, transient.

CALIX: Exactly right! Can we just quote him?

BANNISTER: As an interdisciplinary artist, someone who weaves live and pre-recorded insect sounds into works, I would assume much of your aim is to test and augment these tensions and harmonies between disciplines. You collaborate with scientists, other musicians, [and] artists. Do you feel like the technical borders between disciplines are fading away?

CALIX: Absolutely. People often think of artists and scientists as being diametrically opposed, but we both believe something is possible. We have [a hypothesis] and then we do everything to make it possible, but we don’t know if it’s possible! All the scientists I’ve worked with have a natural, easy fit with me. The solutions they find are truly creative. All scientists, in some way, are artists.

BANNISTER: I feel like that desire to separate professions is a hangover from the 19th century and the age of discovery. Everything was compartmentalized and filed.

CALIX: Like the Dewey Decimal System. Yes, I think that age of specialism is disappearing, the idea we’re confined to departments, where you make glass jugs, and all you’re allowed to do is make glass jugs. I think those days are [phasing out]. Strangely, our approach to categorizing is still slightly stuck. We still want to say, “That’s the glass jug maker!” The reason I likened my work to opera earlier is because opera was the first truly multi-media event ever. They said, “We’ve got all this stuff we can do! We can sing, we can dance, we can paint, we can make costumes–let’s use it all!” If it’s required for the work, I’ll use it.

BANNISTER: What do you think the role of the artist should be today?

CALIX: I think it’s about being provocative. I don’t mean shocking, but you have to provoke people into action. As an artist, you ask people for their time. It’s the most precious thing anyone has. I’m asking audiences to come to my work and spend some time with it. What I’m really doing, of course, is asking people to take time for themselves.

INSIDE THERE FALLS RUNS FROM JANUARY 8-17 AT SYDNEY’S CARRIAGEWORKS BAY 17, PRESENTED IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE 2015 SYDNEY FESTIVAL AND SYDNEY DANCE COMPANY.