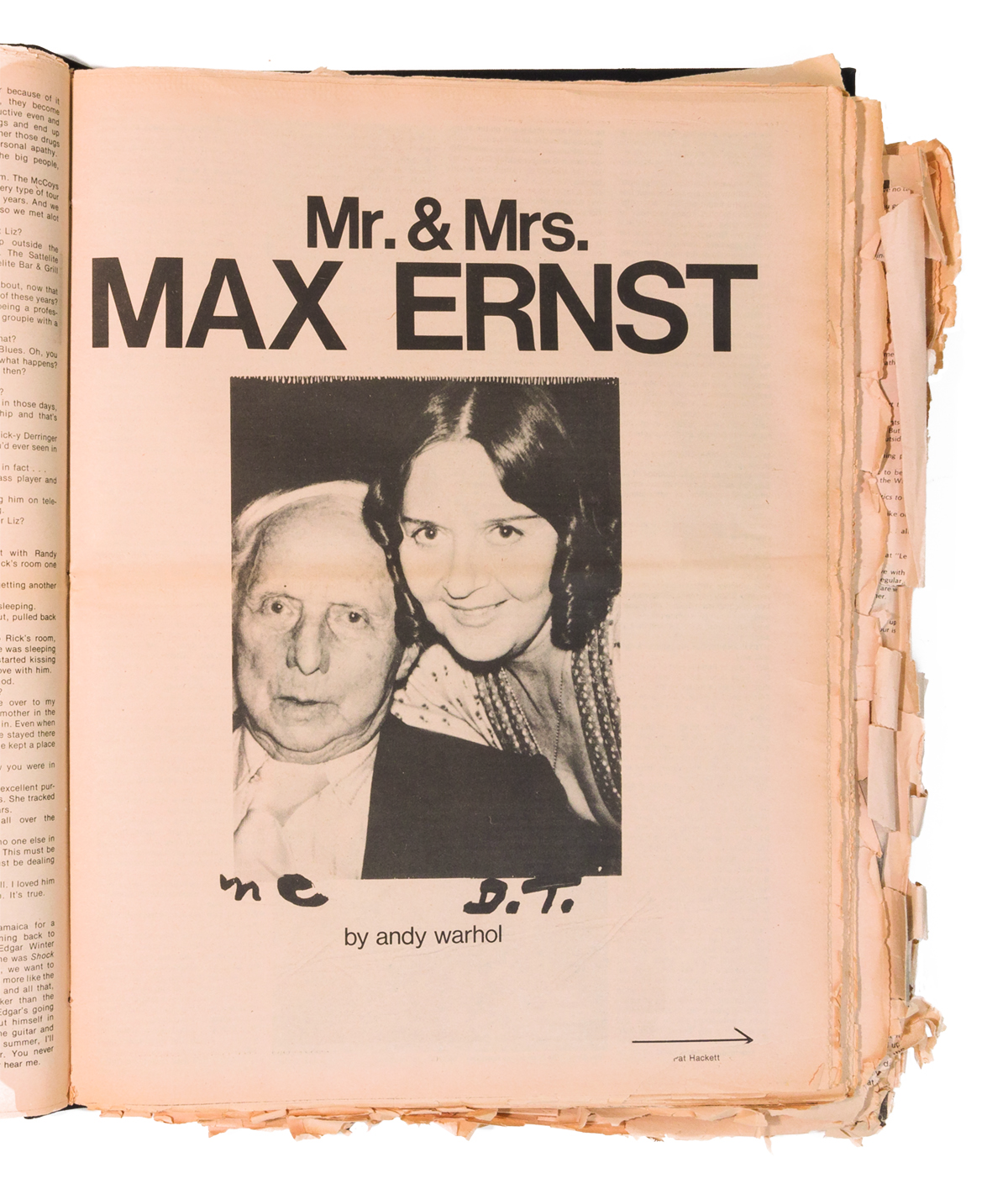

Mr. and Mrs. Ernst Meet Mr. Warhol

This story is part of a collection celebrating the best—and wildest—Warhol conversations from the Interview archives.

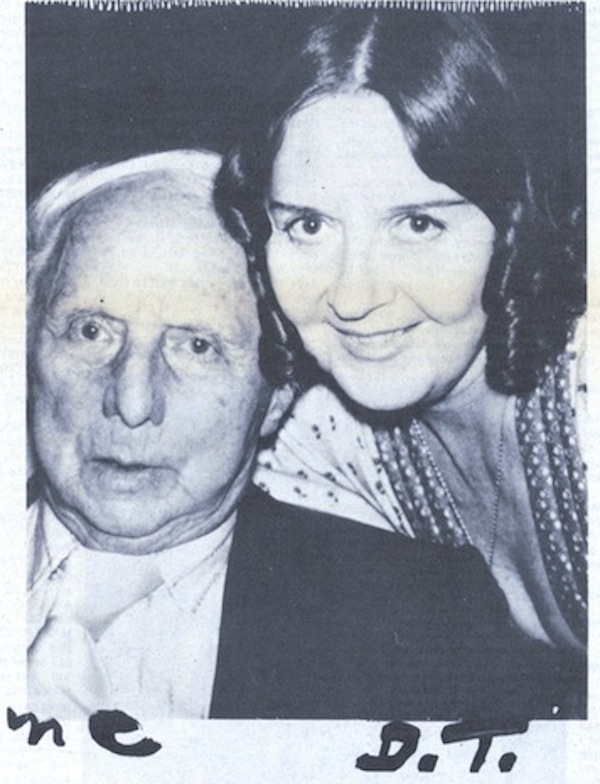

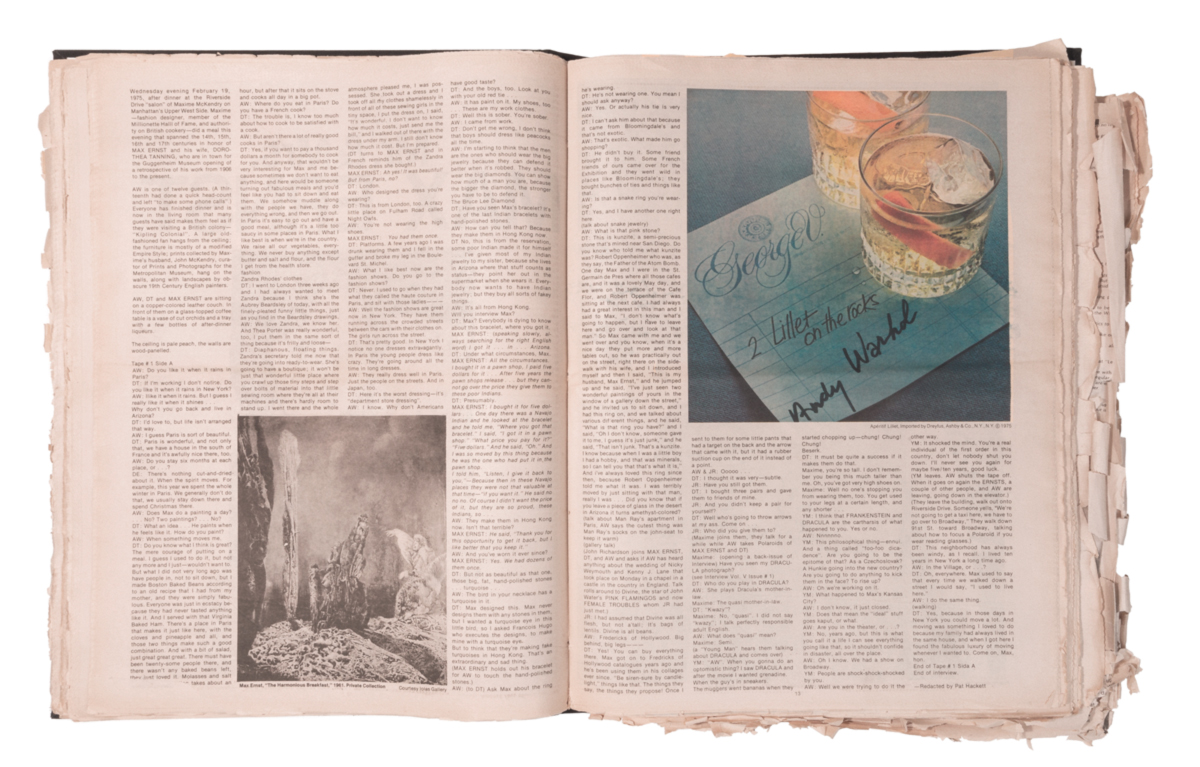

In February 1975, after dinner at the Riverside Drive “salon” of Maxime McKendry on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Maxime—fashion designer, member of the Millionette Hall of Fame, and authority on British cooker—did a meal that spanned the 14th, 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries in honor of Max Ernst and his wife, Dorothea Tanning, who are in town for the Guggenheim Museum opening of a retrospective of his work from 1906 to the present.

Andy Warhol was one of 12 guests. (A 13th had done a quick head-count and left “to make some phone calls.”) Everyone had finished dinner and was in the living room that many guests said made them feel as if they were visiting a British colony—”Kipling Colonial.” A large, old-fashioned fan hung from the ceiling; the furniture was mostly of a modified Empire Style; prints collected by Maxime’s husband, John McKendry, curator of prints and photographs for the Metropolitan Museum, hung on the walls, along with landscapes by obscure 19th Century English painters.

Warhol, Tanning, and Ernst sat on a copper-colored leather couch. In front of them on a glass-topped coffee table was a vase of cut orchids and a tray with a few bottles of after-dinner liqueurs. The ceiling is pale peach, the walls were wood-panelled.

–——

ANDY WARHOL: Do you like it when it rains in Paris?

DOROTHEA TANNING: If I’m working I don’t notice. Do you like it when it rains in New York?

WARHOL: I like it when it rains. But I guess I really like it when it shines… Why don’t you go back and live in Arizona?

TANNING: I’d love to, but life isn’t arranged that way.

WARHOL: I guess Paris is sort of beautiful.

TANNING: Paris is wonderful, and not only that, we have a house in the south of France and it’s awfully nice there, too.

WARHOL: Do you stay six months at each place, or…?

TANNING: There’s nothing cut-and-dried about it. When the spirit moves. For example, this year we spent the whole winter in Paris. We generally don’t do that, we usually stay down there and spend Christmas there.

WARHOL: Does Max do a painting a day? …No? Two paintings? …No?

TANNING: What an idea… He paints when he feels like it. How do you paint?

WARHOL: When something moves me.

TANNING: Do you know what I think is great? The mere courage of putting on a meal. I guess I used to do it, but not any more and I just wouldn’t want to. But what I did not very long ago was have people in, not to sit down, but I made Boston baked beans according to an old recipe that I had from my mother, and they were simply fabulous. Everyone was just in ecstasy because they had never tasted anything like it. And I served with that Virginia baked ham. There’s a nice place in Paris that makes it just like here, with the cloves and pineapple and all, and those two things make such a good combination. And with a bit of salad, just great, great, great. There must have been 20-some people there, and there wasn’t any baked beans left, they just loved it. Molasses and salt pork. The preparation takes about an hour, but after that it sits on the stove and cooks all day in a big pot.

WARHOL: Where do you eat in Paris? Do you have a French cook?

TANNING: The trouble is, I know too much about how to cook to be satisfied with a cook.

WARHOL: But aren’t there a lot of really good cooks in Paris?

TANNING: Yes, if you want to pay a thousand dollars a month for somebody to cook for you. And anyway, that wouldn’t be very interesting for Max and me because sometimes we don’t want to eat anything, and here would be someone turning out fabulous meals and you’d feel like you had to sit down and eat them. We somehow muddle along with the people we have, they do everything wrong, and then we go out. In Paris it’s easy to go out and have a good meal, although it’s a little too saucy in some places in Paris. What I like best is when we’re in the country. We raise all our vegetables, everything. We never buy anything except butter and salt and the flour I get from the health store.

TANNING: I went to London three weeks ago and I had always wanted to meet Zandra Rhodes because I think she’s the Aubrey Beardsley of today, with all the finely-pleated funny little things, just as you find in the Beardsley drawings.

WARHOL: We love Zandra, we know her. And Thea Porter was really wonderful, too, I put them in the same sort of thing because it’s frilly and loose—

TANNING: Diaphanous, floating things. Zandra’s secretary told me now that they’re going into ready-to-wear. She’s going to have a boutique; it won’t be just that wonderful little place where you crawl up those tiny steps and step over bolts of material into that little sewing room where they’re all at their machines and there’s hardly room to stand up. I went there and the whole atmosphere pleased me, I was possessed. She took out a dress and I took off all my clothes and shamelessly in front of all these sewing girls in the tiny space, I put the dress on, I said, “It’s wonderful, I don’t want to know how much it costs, just send me the bill,” and walked out of there with the dress under my arm. I still don’t know how much it cost. But I’m prepared. [Tanning turns to Max Ernst and in French reminds him of the Zandra Rhodes dress she bought.]

MAX ERNST: Ah yes! It was beautiful! But from Paris, no?

TANNING: London.

WARHOL: Who designed the dress you’re wearing?

TANNING: This is from London, too. A crazy little place on Fulham Road called Night Owls.

WARHOL: You’re not wearing the high shoes.

ERNST: You had them once.

TANNING: Platforms. A few years ago I was drunk wearing them and I fell in the gutter and broke my leg in the Boulevard St. Michel.

WARHOL: What I like best now are the fashion shows. Do you go to the fashion shows?

TANNING: Never. I used to go when they had what they called the haute couture in Paris, and sit with those ladies—

WARHOL: Well the fashion shows are great now in New York. They have them running across the crowded streets between the cars with their clothes on. The girls run across the street.

TANNING: That’s pretty good. In New York I notice no one dresses extravagantly. In Paris the young people dress like crazy. They’re going around all the time in long dresses.

WARHOL: They really dress well in Paris. Just the people on the streets. And in Japan, too.

TANNING: Here it’s the worst dressing—it’s “department store dressing.”

WARHOL: I know. Why don’t Americans have good taste?

TANNING: And the boys, too. Look at you with your old red tie…

WARHOL: It has paint on it. My shoes, too… These are my work clothes.

TANNING: Well this is sober. You’re sober.

WARHOL: I came from work.

TANNING: Don’t get me wrong, I don’t think that boys should dress like peacocks all the time.

WARHOL: I’m starting to think that the men are the ones who should wear the big jewelry because they can defend it better when it’s robbed. They should wear the big diamonds. You can show how much of a man you are, because the bigger the diamond, the stronger you have to be to defend it. The Bruce Lee Diamond.

TANNING: Have you seen Max’s bracelets with hand-polished stones.

WARHOL: How can you tell that?

TANNING: This is from the reservation, some poor Indian made it for himself… I’ve given most of my Indian jewelry to my sister, because she lives in Arizona where that stuff counts in status—they point her out in the supermarket when she wears it. Everybody now wants to have Indian jewelry; but they buy all sorts of fakey things.

WARHOL: Will you interview Max?

TANNING: Max? Everyone is dying to know about this bracelet, where you got it.

ERNST: [speaking slowly, always searching for the right English word] I got it… in… Arizona.

TANNING: Under what circumstances, Max?

ERNST: All the circumstances. I bought it in a pawn shop. I paid five dollars for it. After five years the pawn shop release… but they cannot go over the price they give to these poor Indians.

TANNING: Presumably.

ERNST: I bought it for five dollars. One day there was a Navajo Indian and he looked at the bracelet and he told me, “Where you got that bracelet?” I said, “I got it in a pawn shop.” “What price you pay for it?” “Five dollars.” And he said, “Oh.” And I was so moved by this thing because he was the one who had put it in the pawn shop. I told him, “Listen, I give it back to you,” —Because then in these Navajo places they were not that valuable at that time—”if you want it.” He said no, no, no. Of course I didn’t want the price of it, but they are so proud, these Indians, so…

WARHOL: They make them in Hong Kong now. Isn’t that terrible?

ERNST: He said, “Thank you for this opportunity to get it back, but I like better that you keep it.”

WARHOL: And you’ve worn it ever since?

ERNST: Yes. We had dozens of them once.

TANNING: But not as beautiful as that one, those big, fat, hand-polished stones… turquoise…

WARHOL: The bird in your necklace has a turquoise in it.

TANNING: Max designed this. Max never designs them with any stones in them, but I wanted a turquoise eye in this little bird, so I asked Francois Hugo who executes the designs, to make mine with a turquoise eye.

WARHOL: [to Tanning] Ask Max about the ring he’s wearing.

TANNING: He’s not wearing one. You mean I should ask anyway?

WARHOL: Yes. Or actually his tie is very nice.

TANNING: I can’t ask him about that because it came from Bloomingdale’s and that’s not exotic.

WARHOL: That’s exotic. What made him go shopping?

TANNING: He didn’t buy it. Some friend brought it to him. Some French friends of ours came over for the exhibition and they went wild in places like Bloomingdale’s; they bought bunches of ties and things like that.

WARHOL: Is that a snake ring you’re wearing?

TANNING: Yes, and I have another one right here.

WARHOL: What is that pink stone?

TANNING: This is kunzite, a semi-precious stone that’s mined near San Diego. Do you know who told me what kunzite was? Robert Oppenheimer who was, as they say, the Father of the Atom Bomb. One day Max and I were in the St. Germain de Pres where all those cafes are, and it was a lovely May day, and we were on the terrace of the Café Fior, and Robert Oppenheimer was sitting at the next café. I had always had a great interest in this man and I said to Max, “I don’t know what’s going to happen, but I have to leave here and go over and look at that man.” So Max came with me and we went over and you know, when it’s a nice day they put more and more tables out, so he was practically out on the street, right there on the sidewalk with his wife, and I introduced myself and then I said, “This is my husband, Max Ernst,” and he jumped up and he said, “I’ve just seen two wonderful paintings of yours in the window of a gallery down the street,” and he invited us to sit down, and I had this ring on, and we talked about various different things, and he said, “What is that ring you have?” and I said, “Oh I don’t know, someone gave it to me, I guess it’s just junk,” and he said, “That isn’t junk. That’s a kunzite. I know because when I was a little boy I had a hobby, and that was minerals, so I can tell you that that’s what it is.” And I’ve always loved this ring since then, because Robert Oppenheimer told me what it was. I was terribly moved by just sitting with that man, really I was… Did you know that if you leave a piece of glass in the desert in Arizona it turns amethyst-colored?

[John Richardson joins Ernst, Tanning, and Warol and asks if Warhol has heard anything about the wedding of Nicky Weymouth and Kenny J. Lane that took place on Monday in a chapel in a castle in the country in England. Talk rolls around to Divine, the star of John Water’s Pink Flamingos and now Female Troubles whom Richardson had just met.]

JOHN RICHARDSON: I had assumed that Divine was all flesh, but not a’tall: It’s bags of lentils, Divine is all beans.

WARHOL: Fredericks of Hollywood. Big behind, big legs—

TANNING: Yes! You can buy everything there. Max got on to Fredericks of Hollywood catalogues years ago and he’s been using them in his collages ever since. “Be siren—sure by candlelight.” Things like that. The things they say, the things they propose! Once I sent to them for some little pants that had a target on the back and the arrow that came with it, but it had a rubber suction cup on the end of it instead of a point.

WARHOL & RICHARDSON: Ooooo…

TANNING: I thought it was very—subtle.

RICHARDSON: Have you still got them?

TANNING: I bought three pairs and gave them to friends of mine.

RICHARDSON: And you didn’t keep a pair for yourself?

TANNING: Well, who’s going to throw arrows at my ass. Come on…

RICHARDSON: Who did you give them to?

[Maxime McKendry joins them, they talk for a while while Warhol takes Polaroids of Ernst and Tanning]

MCKENDRY: [opening a back-issue of Interview] Have you seen my Dracula photograph?

TANNING: Who do you play in Dracula?

WARHOL: She plays Dracula’s mother-in-law.

MCKENDRY: The quasi mother-in-law.

TANNING: “Kwazy?”

MCKENDRY: No, “quasi.” I did not say “kwazy;” I talk perfectly responsible adult English.

WARHOL: What does “quasi” mean?

MCKENDRY: Semi.

[a young man hears them talking about Dracula and comes over]

YOUNG MAN: [to Warhol] When you gonna do an optimistic thing? I saw Dracula and after the movie I wanted grenadine. When the guy’s in sneakers. The muggers went bananas when they started chopping up—chung! Chung! Chung! Berserk.

TANNING: It must be quite a success if it makes them do that. Maxime, you’re so tall. I don’t remember you being this much taller than me. Oh, you’ve got very high shoes on.

MCKENDRY: Well no one’s stopping you from wearing them, too. You get used to your legs at a certain length and any shorter…

YOUNG MAN: I think that Frankenstein and Dracula are the catharsis of what happened to you. Yes or no.

WARHOL: Nnnnnno.

YOUNG MAN: This philosophical thing—ennui. And a thing called “foo-foo dicadence.” Are you going to be the epitome of that? As a Czechoslovak? A Hunkie going into the new country? Are you going to do anything to kick them in the face? To rise up?

WARHOL: Oh, we’re working on it.

YOUNG MAN: What happened to Max’s Kansas City?

WARHOL: I don’t know, it just closed.

YOUNG MAN: Does that mean the “ideal” stuff goes kaput, or what?

WARHOL: Are you in the theatre, or…?

YOUNG MAN: No, years ago, but this is what you call it a life—I can see everything going like that, so it shouldn’t confide in disaster, all over the place.

WARHOL: Oh I know. We had a show on Broadway.

YOUNG MAN: People are shock-shock-shocked by you.

WARHOL: Well we were trying to do it the other way.

YOUNG MAN: It shocked the mind. You’re a real individual of the first order in this country, don’t let nobody shut you down. I’ll never see you again for maybe five/10 years, good luck.

[The young man leaves. Warhol shuts the tape off. When it goes on again Ernst, a couple of other people, and Warhol are leaving, going down in the elevator. They leave the building, walk out onto Riverside Drive. Someone yells, “We’re not going to get a taxi here, we have to go over to Broadway.” They walk down 91st Street toward Broadway, talking about how to focus a Polaroid if you wear reading glasses.]

TANNING: This neighborhood has always been windy, as I recall. I lived 10 years in New York a long time ago.

WARHOL: In the Village, or…?

TANNING: Oh, everywhere. Max used to say that every time we walked down a street I would say, “I used to live here.”

WARHOL: I do the same thing.

TANNING: Yes, because in those days in New York you could move a lot. And moving was something I loved to do because my family had always lived in the same house, and when I got here I found the fabulous luxury of moving whenever I wanted to. Come on, Max, hon.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE FEBRUARY 1975 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

———

Read more stories from the Celebrating Warhol collection.