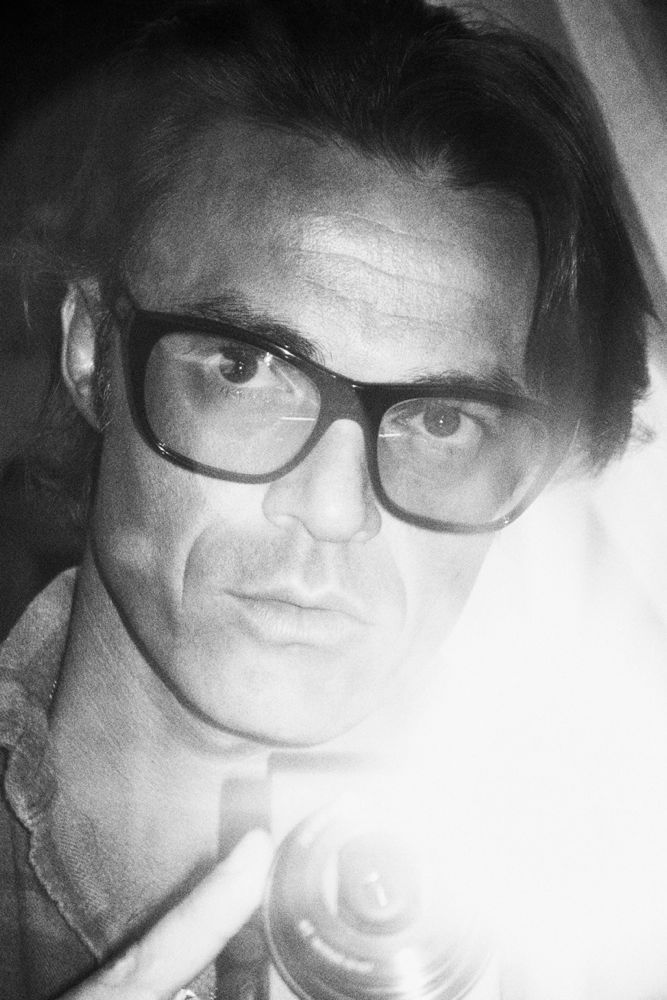

Mario Sorrenti

My work was my life, and my life was my work, and there was a kind of blur between reality and what was being created. Mario Sorrenti

Having arrived at a sweet spot in his career as a fashion photographer, Mario Sorrenti has done just what he is not supposed to do. Instead of assembling a luxe volume of pretty pictures of pretty women in pretty clothes, the 41-year-old Sorrenti is publishing Draw Blood for Proof (Steidldangin), a feral, inexhaustible book of images, thrice removed from their original source: It’s actually a one-to-one-scale reproduction of a 2004 gallery show in which he exhibited collages of various pictures he shot in his twenties—along with scribbled notes, portraits both formal and casual, tear sheets of other people’s work, and, here and there, images from his own commercial work. The result is a book very much reflective of its maker: emotional, funny, boundlessly energetic, both raunchy and courtly, sophisticated, affectionate, enthusiastic, naïve, and excitable.

I’ve met Sorrenti just once, about a year ago, when I was asked to contribute a piece of writing to the book. But I feel like I’ve known him all my life. This conversation took place over the phone. I was at my home in Austin, Texas. I have no idea where he was.

JIM LEWIS: How long have you been working on Draw Blood? It’s been a haul, hasn’t it?

MARIO SORRENTI: It’s been a really long time. It was originally a collage on my loft wall in New York; then I moved and I had to pack everything up. The exhibition happened in 2004, and then we photographed the whole thing. So the idea actually started in 2001 or something like that. It’s been 12 years.

LEWIS: Is it a relief to be finished? Or are you going to miss it?

SORRENTI: It’s been a huge awakening, to be honest with you—because the work comes out of the first 10 years of my photographic career—probably the most intensely creative time I’ve had. I was shooting Polaroids all the time, I was creating diaries, I was painting, I was drawing. My work was my life, and my life was my work, and there was a kind of blur between reality and what was being created. It wasn’t about money. It wasn’t about getting a picture or a credit from a client. I had no responsibilities. I didn’t give a shit about anything. It was just me kind of blazing through.

LEWIS: A year ago, I asked you if you felt this book was some kind of summing up or reckoning, and you said no. Now it sounds like maybe you do feel that way.

SORRENTI: I do feel that way now. I was looking through the dummy of the book about five months ago and I thought, “What the fuck happened to that person? Where is that person? What the hell is going on? What am I doing now?” Not that what I’m doing now is negative, it’s just changed so much, and that time seems so far away, so surreal. But I think it was really good because . . . I don’t want to change my life, but maybe I need to go much deeper, make sure that I don’t spend the next 10 years just trapped in a weird bubble, you know what I mean? A superficial bubble.

LEWIS: When I look back at myself in my twenties, I often find myself thinking, Who was that?

SORRENTI: I’m still that person, but I’m living another reality in a way. Those first 10 years were really important for me. They were the foundations of who I am today. They’re my life, my work, my ideas, my thoughts, my family. They’re the births, the deaths, the pain . . . So that book is my life, a retrospective dream of my life. But back then, I was fighting against being a commercial photographer, a fashion photographer. And then one day—I don’t know why—I just kind of said, “You know what? Fuck, man, I have an amazing opportunity, so I’m just going to pursue it.” At the same time, my brother passed away [Davide Sorrenti, also a photographer, died from complications of his congenital blood ailment and heroin use in 1997], and right after that, my kids were born, and it made me grateful for the things that I had in my life. It made me really focus on my responsibilities. But I just turned 41 last October, and now I’m thinking, Okay, I want the next 10 years to be—not the same as it was back then, because it will never be the same—but I want it to be more important for me, as a photographer, and less about some advertising campaign that I have to do.

LEWIS: Can you control it? Or do you just kind of ride through life hanging on by your fingertips?

SORRENTI: I don’t know. I know that you have to be courageous in some way, but I don’t know what’s going to happen. I might just end up disappearing. I don’t know if photography is going to be relevant in 10 years’ time. I don’t know if most magazines are going to be around. I’m just trying to keep my eyes open and get ahead of the game, so that when things change, somehow I’m already there.

LEWIS: There are a lot of pictures in Draw Blood.

SORRENTI: Maybe a thousand.

LEWIS: How did you choose them?

SORRENTI: Oh, I didn’t choose them. I just kept them. All the Polaroids that didn’t go into my diary, I kept in bags and boxes. I have weird images and ideas that kind of pop into my mind, and then there’s a point where I say, “I’ve got to do it.” And I don’t know what the final product is going to be—whatever comes out is the outcome. It’s like a spark, something that’s just got to happen. I have this incredible urge and desire to do this thing, and it’s like life or death.

LEWIS: I lent the book to a friend of mine. She thought it was going to be some fashion-y book about women and clothes, and she really appreciated the fact that it was about men as much as women.

SORRENTI: I’m pretty open. I’m not afraid of men. I’m not afraid of women. I’m not afraid of sex and sexuality.

It’s part of me, and it comes out in the photograph. It’s as if at that moment when I’m taking pictures, I’m not a man and I’m not a woman. If I see a moment that seems true to me, that seems honest, whether it’s female or male, it’s part of me as well.

LEWIS: You don’t strike me as someone who has prolems with intamacy, like a lot of photographers. But I have to ask: What are you afraid of?

SORRENTI: [laughs] Well, to be honest with you, before I had kids, I wasn’t really afraid of anything. And then—it sounds very normal, I guess—the moment you have kids, you become afraid of everything that could happen.

LEWIS: Are you afraid of getting old?

SORRENTI: Not at all. That kind of inspires me. I was never afraid of getting old. I remember being young and thinking, Wow, I can’t wait until I’m older because I feel like everything is going to happen then. [laughs] I don’t want to sound pretentious or anything, but I’m always one of the first ones to say, “Let’s try that.”

JIM LEWIS IS AN ESSAYIST, REPORTER, AND THE AUTHOR OF THREE NOVELS, MOST RECENTLY THE KING IS DEAD (KNOPF)