Maria Hassabi’s Premiere League

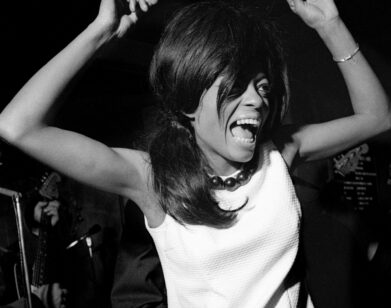

ABOVE: MARIA HASSABI, PREMIERE, 2013. PHOTO COURTESY OF MARIALENA MAROUDI

Life can become a living performance, but most people eventually disappear backstage. Whether relaxing in a dressing room behind the curtain, drinking coffee in a café, or reading a book in bed, solitary moments give us time to take a break and breathe. However, many performance artists never stop performing. For Maria Hassabi, taking a break just means more work—more critical thinking, more dancing, more experimentation.

In her Chelsea studio, two large Oriental area rugs divide the floor space and two oversized chandeliers hang from the ceiling. Inspirational images hang on the wall adjacent to a black leather couch. Despite the fact that these props, which were used in prior performances, surround her, Hassabi says she does not consider herself a performance artist.

“I don’t call what I do performance art,” she says. “I don’t really care about titles…I’m an artist. I perform. I make shows.”

The Cyprus-born artist moved to the U.S. to attend the California Institute of the Arts in 1990. Following graduation, she moved to New York in pursuit of art. “There was an ability in the city,” Hassabi recalls. “You went crazy in New York. Everything was there.” Now, nearly 10 years later, the self-proclaimed jaded New Yorker performs around the world.

But despite the cultural shifts she experienced, Hassabi never contemplates her Egyptian childhood. Rather, she draws inspiration from the spectacular now. “I don’t know if it’s just having a busy life, but I never look back,” she says. “I don’t know if it’s my personality; I just don’t reflect.”

As she sipped tea and smoked hand-rolled cigarettes, Hassabi spoke about her upcoming performance, PREMIERE, and her role as an artist. PREMIERE will debut on November 6 at The Kitchen as part of New York’s performing arts festival, Performa 13.

EMILY MCDERMOTT: For PREMIERE, what was your inspiration?

MARIA HASSABI: It was really playing with the idea of “premiere”—all of the things that you go through—the struggle, the excitement, all of it. It’s the moment when the audience gets to validate that anything is a work of art. A lot of what I’m dealing with in PREMIERE is what I value as a work of art, what the expectation of a work of art is.

MCDERMOTT: What can we expect to see in PREMIERE?

HASSABI: Five people taking their time. The setting is quite intense, quite present.

MCDERMOTT: In one of your performances, there were no chairs, and you forced people to move and create space. Will it be something to that effect?

HASSABI: People are asking me, “Should I bring a pillow?” [laughs] I’m like, “Don’t worry. You’re getting a seat this time.” “Premiere,” for me, is such a theatrical term, so I didn’t want to mess that up. You are in the theater; you are taking a seat.

MCDERMOTT: What makes you refer to yourself as a director/choreographer instead of a performance artist?

HASSABI: I don’t really care about titles. If somebody says, “You’re a performance artist,” I say, “sure.” But usually the title I give myself is director/choreographer because it’s the market that I work within. I’m an artist. I perform. I make shows. I deal a lot with space, time, the body and people. You put a stem in yourself within the genre that you’re working. Then when the work ends up going to museums, it doesn’t matter if it’s called something else.

MCDERMOTT: You perform live, so do you think it changes the meaning of the works when they go to a museum and are represented through pictures or video?

HASSABI: I don’t think so. The work is durational; it takes place in time. Of course a picture is still—it’s capturing a millisecond —but my work is about images, and images are flat. It’s nice to see the work in photographs. Your imagination can go. What people are reflecting might not even be my piece, but that happens in the live performance. What I have in mind might not be what you read through it.

MCDERMOTT: What do you typically have in mind when you’re creating a piece?

HASSABI: It varies on the theme of the work each time. Something that has been more consistent in my work is style: it is slow, sculpture-esque, very precise.

MCDERMOTT: The pieces that I’ve seen have been very minimal in their amount of movement. What do you think draws you towards that?

HASSABI: To try to understand what I’m doing. Trying to always clean it and understand what it is, I end up paring it down. People in the beginning called me a formalist and I was like, “Really? I’m a formalist?” But formalism is so connected with language, and language is not just the verbal, but creating a language. People talk about dance as experiential art, but for me it’s not about that. It’s experiential because it’s related to time, but I always try to create a language. It is abstract; it’s not a narrative.

MCDERMOTT: That’s a good way to think about it. When did you first become interested in dancing?

HASSABI: I always put shows up for my parents, for their friends, [and] in school with friends. I always went to the theater as a kid, so I always thought it was more theater that I was interested in. At some moment I was like, “I can do theater later. I should dance now.” It was very simple, something like that.

MCDERMOTT: What’s a typical day in the life of Maria?

HASSABI: This is my third premiere in one year, including performing and touring other works and performing for other people. It’s been a crazy year in terms of schedules and high pressure. It’s my own pressure that I put to myself, because I want to understand every work. There are meetings, endless hours in the studio, performing, traveling and changing cities. Every time you arrive in a new place it takes time. You’re dealing with the now.

MCDERMOTT: How do you deal with all of the pressure and stress?

HASSABI: I try to stay calm. I quit coffee. I miss it when I smell it sometimes. [laughs] I’m trying to understand how to still relate to people, because you get so focused on your own world. When you’re working with such detailed work, it takes hours. For example, in July I ended up flying a friend with me just so I could see her. We were rehearsing 10-hour days, but at night I knew I was going to hang out with her. Now, this work [PREMIERE] is a group piece, so I’m around beautiful people. These are people that I chose because I wanted to hang out with them. I love them as performers, but I like them as people. It’s not as lonely.

MCDERMOTT: I was going to ask about that. You’re working with four people and your other performances have all been solos or duets. What made you decide to bring in more people for this piece?

HASSABI: I was ready. It doesn’t mean that from now on I always want to make group pieces. I like the smallness of a solo, but I was curious to see how my ideas would translate in a bigger group of people. They’re all so distinct, this group of people. What I wanted the most was to keep their individuality within the frame of this work, within this prison of this stylist. It’s been difficult, but it’s good because what I see the most when I look at the work—I see them. I’m very happy.

MCDERMOTT: Where do you draw your inspiration from?

HASSABI: In the beginning it was image-based. I really love looking at images. I love the power that an image has. Uncovering how an image could be supported in live performance was a challenge for me, but now I’ve been doing it for so long that I don’t go back to look. We look at images all the time, our life is full of images, but I don’t give myself time to look over an image and copy its posture anymore. This work SoloShow was all about women and iconic images of women. I had to look at how lots of people expressed that. I went all the way from antiquity to Rodin to women on the red carpet.

MCDERMOTT: A professor always told us to stand naked in our rooms with a book of Rodin sculptures, look in a mirror and try to imitate them because it’s so incredibly painful. Do you try to imitate Rodin’s sculptures?

HASSABI: I did. I did a lot. For SoloShow, there’s a lot of Rodin. Then for a while a lot of the postures that I discovered, that I explored, followed in my other works. It became more mine than Rodin’s. It was mine because it was my adaptation, but it was difficult to get them into my body or teach them. Once you find out how to get in it, you slowly make it your own.

MCDERMOTT: How does it feel when it’s your own?

HASSABI: Like you stole something and you made it your own. [laughs] But it feels more comfortable. It’s like you borrow somebody’s shirt and the first time you wear it, it really feels like somebody else’s shirt. But the third time you wear it, it feels like, “I don’t want to give it back now. This feels good.” [laughs]

MCDERMOTT: Are there any specific dancers or choreographers whose work you admire?

HASSABI: Yes, but the funny thing is that when you’re working so much on something, you forget the others within your field. My mind goes more to somebody who doesn’t do what I do. I think of a visual artist or somebody who is not dealing with the same form I’m dealing with. I usually don’t draw my inspiration from dance.

MCDERMOTT: A dream performance space—where would it be?

HASSABI: I like performance spaces that have a character and I can work with its character. The space that I performed at in Venice this summer is not even a performance space. It’s a gymnasium. It was this challenge of how to make the work work in there. Big theaters can also be scary because they’re so unpersonable. In making works that are so detailed, there’s a fear of, “Oh people are not going to be able to see.” I find that exciting—not that they’re not going to see, but how to adapt a work without changing its essential [meaning]. So there’s not a dream space. I love performing in the streets as well. I love open spaces, and I love small spaces. It’s not about being democratic. It’s a challenge with each space to find its personality.

MCDERMOTT: Do you base your performances on where you’re going to perform?

HASSABI: Definitely. For PREMIERE, since I know it premieres at The Kitchen, a lot of my thinking is about “This is happening for The Kitchen,” but I already know where we’re performing it next. In June we have a residency in a theater in Brussels, which has a really big stage. It’s going to be a very different product when we do it there. It cannot be the same. It won’t work on that big stage.

MCDERMOTT: How would you define your philosophy toward art?

HASSABI: Ideally, you want to touch people. You want to open up a side of their mind that is going to make them think in a new way about being a human being. I’m trying to give time to people to look at things—slow them, bring them down. [My work] is an artificial reality. It’s not a picture of our lives. Since it is artificial, I can slow it down and focus on the little things that usually get dismissed. It’s not like we’re going to the moon. It’s nothing extraordinary. It’s hopefully quite the opposite, something very simple.

PREMIERE DEBUTS NOVEMBER 6 AT THE KITCHEN. FOR MORE ON MARIA HASSABI, VISIT HER WEBSITE.