Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s Fictive Figures

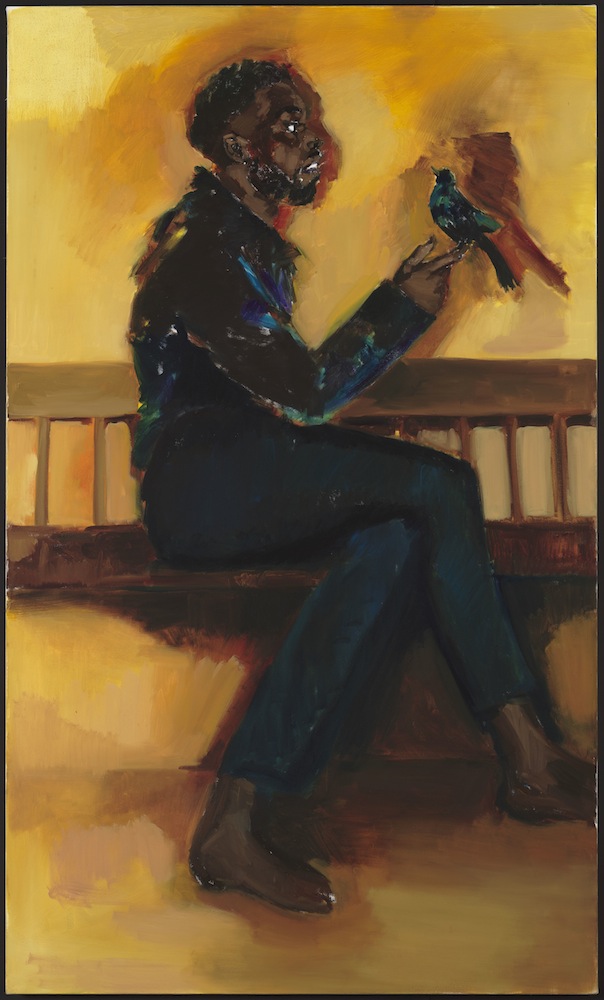

British-Ghanaian painter and writer Lynette Yiadom-Boakye‘s recently opened solo exhibition, “Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Under-Song For A Cipher,” at the New Museum in New York features 17 large-scale, low-hanging canvases of fictional black figures. They are engaged in moments of absolute abandon, repose, and contemplation. Mercy Over Matter (2017) brings to life a scene of a barefoot male, sitting on a wooden bench, legs crossed with an emerald bird resting on his sable index finger. The man and bird gaze at each other admiringly. Hues of blue, green, yellow, and red flicker through his body. Wiped away is the current weary state of the world. It is replaced with a highly emotive, earthy, orange-yellow background that feels domestic and perennial. “When I think of the figure, I think of immortality or an otherness that is just out of this world, representing an endless possibility,” says Yiadom-Boakye, who was the first black woman shortlisted for the prestigious Turner Prize in 2013. “For me, the act of painting reflects blending in or standing out, being ignored or prominent. It’s a psychological space, a rumination.” The way Yiadom-Boakye moves paint across linen canvases recalls the 19th-century portraiture of John Singer Sargent and Édouard Manet. It is as if her figures are in private states of salvation, presenting a version of themselves that the popular imagination refuses to admit is achievable for the black body. That’s the power of her fictions: they are pure reflections of real life, yet somehow hard to see.

The fantasy and rhythmic nature of a Yiadom-Boakye painting can be glimpsed in artist’s written works of fiction, too. In an excerpt of her poem “Problems With the Moon” she writes:

The Clearest Of Problems With

The Moon

Came when the dogs, wolves, foxes

and other

Canine derivatives, lost their howls,

barks

And nocturnal ecstasies to silence,

Shrugging and Eyeing each other

in Mists

Of Cold and Total Incredulity

Under trees, in kennels, dens,

car-parks and

Out-houses. In blackness of night,

low-lit

By lamp and that Problematic Moon.

The day before Yiadom-Boakye’s exhibition opened, we shared a slice of chocolate cake at a bakery a block away from the New Museum, and mused over building black characters on the page and canvas.

ANTWAUN SARGENT: The most fascinating thing about your paintings to me is that the figures are complete works of fiction.

LYNETTE YIADOM-BOAKYE: Everything’s a composite. I work from sources. I make scrapbooks, I make drawings, and collect things that I might use later, so they are all very literal compositions in the way that I pull things together. A lot of that decision-making happens on the painting itself. In each case it’s a negotiation of how I want each figure to fill the space. In the show, there are recurring things like a seated male, but how they are placed on the seat—what they are doing, where they are looking—changes. Across all of the works it was about thinking through what the gesture was; it affects how you read across it. I always wanted a show to be a kind of dialogue between works, even though I don’t necessarily compose them strictly in that way. As I am working in the studio, there a lot of things are around me that I am thinking about. I normally keep one painting up during the whole duration of working on a body of work, so there is that one painting that anchors everything else.

SARGENT: For this show what was that one painting?

YIADOM-BOAKYE: There’s a man with a bird, Mercy Over Matter, with a yellow background that was on the studio wall for the first half of me making the body of work. Then that came off the wall and was put in storage. After that it was a large painting of a woman dancer, Light Of The Lit Wick, with two large circles behind her.

SARGENT: One signature aspect of your painting is that the figure almost blends into its surroundings, because the earth tones of your backdrops are reflective of the character’s dark brown skin tones. There are a lot of things that are being signified but particularly there’s a critique of the hypervisibility, which Ralph Ellison talked about, that renders blackness completely seen and unseen. Is that part of the negotiation between the figure and its surroundings in your work?

YIADOM-BOAKYE: Maybe I think more about black thought than black bodies. When people ask about the aspect of race in the work, they are looking for very simple or easy answers. Part of it is when you think other people are so different than yourself, you imagine that their thoughts aren’t the same. When I think about thought, I think about how much there is that is common.

SARGENT: You write fiction. Has that informed the work at all?

YIADOM-BOAKYE: Not directly, but there is something common. The same thread of logic runs through my writing and painting. It’s something to do with having a particular way of thinking creatively. The things I can’t paint, I write, and the things I can’t write, I paint. There are many ways that I try to write but I don’t consider myself a very accomplished writer. [laughs] I really enjoy building characters and making them nuanced in a way that I am not sure the paintings are. I’ve been really toiling over this detective story.

SARGENT: [laughs] That’s very British of you.

YIADOM-BOAKYE: It is quite British! I love Miss Marple [from Agatha Christie’s novels and short stories]. I am trying to write one about a black policeman and I keep changing the way I am trying to do it. It’s taking me ages because it exhausts me in a different way. If I could paint it, in a way, it would be easier than trying to get all of this information out in words. So as much as there is something common, I do keep the two quite separate. I feel the painting has a certain type of narrative in mind that stops short of an end of a sentence.

SARGENT: Are there similarities or differences in the way that, say, you think about building the black male character sitting in the chair in a painting like Medicine At Playtime, and the black policeman you are trying to currently write?

YIADOM-BOAKYE: In the painting I would allow one gesture that would maybe be a paragraph of description; it’s making a mark on a canvas and allowing that to do what maybe three paragraphs would do. You could infer as much from the gestures as you might from the description on paper, but in the written form my process is somehow slower. I think with painting there is as much as a language as there is with writing, so for me, a very quick washy mark reads as the same as the shortness of a particular sentence. I like short sentences maybe because I like short marks. I don’t know! [laughs]

SARGENT: There has also been an evolution in your use of color from your earlier work to present.

YIADOM-BOAKYE: In most of my early work, I struggled with color as an aspect of painting. I always struggled to introduce it because I felt like I hadn’t had the satisfaction [of it]. It requires a certain type of care that I needed to develop. My process was different as well; there were a lot these earthy dark tones from which I’d try to drag the figure out. I think now I am bolder about color. But I think a lot of that play has to do with what are the colors within a color? What are the colors within a black skin tone? Whether it’s underlaid with blue, orange, or locating the yellow in it, how do you push that forward or pull it back? What does a figure in the landscape with dark skin actually look like? What does green do next to brown? And what goes around the green and brown, in order for the two to make sense? There’s something about the figure looking superimposed that I always felt, certainly in relationship to my own painting, was a failure. It has always been a painterly challenge to qualify a figure by its surroundings so that it represents a real harmony of color.

SARGENT: That’s interesting because in a lot of your work there is only a vague worldly context. As the figure emerges out of the background, I have often wondered, where are they? Is it a place I know? Because they seem totally free, and I wonder, have I ever been in a space where that is possible in real life or psychologically? It all seems completely timeless.

YIADOM-BOAKYE: The timelessness is completely important. It’s partly about removing things that would become in some way nostalgic. There aren’t really any markers of time, like furniture or a particular style of shoe that denote a particular period or place. I think that’s why I like the outdoors, because it removes a sense of time and I want the painting to feel timeless, because it increases that sense of omnipotence. Part of it is, I do think of the work as political, and we think we know what political art is supposed to look like, but I think there are many ways to make it.

SARGENT: Right, we demand an explicitness when we think of political art. If it’s a protest sign, all the better. In what ways is the work political for you?

YIADOM-BOAKYE: Largely by dent of the fact that I am here and I am doing it. Nothing has felt easy or straightforward. It’s hard to pin down what the politics would be, in a way. For me [the politics are] very visual and felt, thought, seen, but not necessarily put into words. The confusions and conditions within the work are the politics. The fact that a lot of the time the first thing people want to talk to me about is the racial angle, which is a part of the work and I am happy to talk about it, but it’s not necessarily the first thing on my mind when I am making something.

SARGENT: I think part of the questioning of the racial markers of the work comes from the way people, both black and white, have been conditioned to look at art. When a black figure lands on a canvas it is believed to be automatically political. In your pictures you seem to say they don’t have to be more than human and they don’t have to signify some kind of moral language; they can simply signify their own personhood.

YIADOM-BOAKYE: That’s totally it. I think that might be a manifesto, in and of itself: let people be. [laughs] I always say the work is not a celebration as such, because that’s sometimes just as weird and excluding and perverse.

SARGENT: When Solange reached out and said your work served as an inspiration for her songwriting process for her really wonderful album, A Seat at the Table, was that in line with the possibilities of what you thought your paintings could do?

YIADOM-BOAKYE: Actually, I thought that was so wonderful. It weirdly felt in keeping with a lot of things I think about, so it was actually quite beautiful. I never would’ve dreamt of anyone doing that, so it was a lovely surprise. I love the idea of people being able to inspire each other. In the way that Prince‘s entire repertoire made me want to be an artist, not necessarily a musician, but an artist because I saw him as an artist. His work ethic was such a huge inspiration to me. This idea of making work every single day as if you are going to die the next, I think is really important for any artist. Prince was a real artist, he got up and worked fucking hard, and that’s what it is about: the art meaning so much and you wanting to get it right. I see that in him, I see that in Solange—that rigor of making. I mean, I wanted to be Prince or Sheila E. when I was a child. I learned to play the drums! Music put pictures in my head.

SARGENT: That makes sense because your paintings rhyme. The way the colors bounce off each other and the light plays on the canvas is not unlike the way we experience sound. Have you painted musicians?

YIADOM-BOAKYE: No. There’s a painting of a man with a guitar bopping around the studio somewhere, but I don’t think it ever saw the light of day. Dancers, yes. Musicians, no.

SARGENT: This show features several paintings of dancers. What is it about dancers that draw you in?

YIADOM-BOAKYE: The very kind of visceral physical power and grace of dancers, and their occasional closeness to losing control. There’s one particular wonderful woman in the show where you can’t tell if she is dancing or about to fall over. She is sort of laughing.

SARGENT: You recently sat for portraitists Kehinde Wiley and Toyin Ojih Odutola. Do you ever think about painting real life figures?

YIADOM-BOAKYE: Most of my training was painting from life. It was incredibly important for me because it allowed me to train my eyes to see everything that is there. But I realized early on that painting from life wasn’t something that I was all that invested in. I was always more interested in the painting than I was the people. For me, removing that as a compulsion offered me a lot more freedom to actually paint and think about color, form, movement, and light. There is something very particular to the figures I do have that lifts them away from reality and offers them the kind of power that I am interested in exploring.

“LYNETTE YIADOM-BOAKYE: UNDER-SONG FOR A CIPHER” IS ON VIEW AT THE NEW MUSEUM IN NEW YORK THROUGH SEPTEMBER 3, 2017.