Face Time for Lucian Freud

The great British painter Lucian Freud (1922—2011) and grandson of Sigmund Freud has a retrospective exhibition of his portraits at London’s National Portrait Gallery [through May 27]. Over 100 of the late artist’s portraits have been sourced from collectors and galleries across the globe, including an unfinished work begun shortly before his death in July 2011. Freud was a key figure in the “London school” of figurative artists working against the abstract zeitgeist of the time, and many of his peers (from Frank Auerbach to Leigh Bowery) posed before his canvas, as well as close family and friends (it is said Freud fathered over 40 children). The exhibition spans a half-century of work, from the lighter surrealist works of Freud’s early paintings through to the brooding impasto nudes of his later career.

Interview spoke with the exhibition’s curator Sarah Howgate on the occasion of this historical exhibition.

DAN THAWLEY: How does it feel to introduce this first portraiture retrospective of Freud’s work to the world in the context of the National Portrait Gallery?

SARAH HOWGATE: It is a huge privilege to show the work of one of the 20th century’s greatest realist painters at the National Portrait Gallery.

THAWLEY: Could you explain the story of the exhibition?

HOWGATE: There are 130 pictures in the exhibition—including paintings and works on paper—and we aim to show the most significant body of portraits by the greatest figurative painter of the last 80 years. The hang is broadly chronological and within that narrative there are groupings of key sitters such as Kitty Garman, Caroline Blackwood, Leigh Bowery, Sue Tilley and the artist’s mother.

THAWLEY: Freud painted family and friends, celebrities and anonymous subjects. Does the show reveal a new depth to his social circles?

HOWGATE: The sheer range of people who sat for Freud is fascinating. He was close to lots of sitters, some of whom sat for several portraits. These ranged from performance artists to members of the criminal underworld, through to Lord Rothschild, and various members of his family. Lucian’s sitters were very dedicated to modeling for him and would be prepared for several sittings often taking place over a long period of time. We have certainly tried to show the diversity of his social circles as one of the threads of this exhibition.

THAWLEY: How would you describe the evolution in style when comparing Freud’s self portraits across the decades?

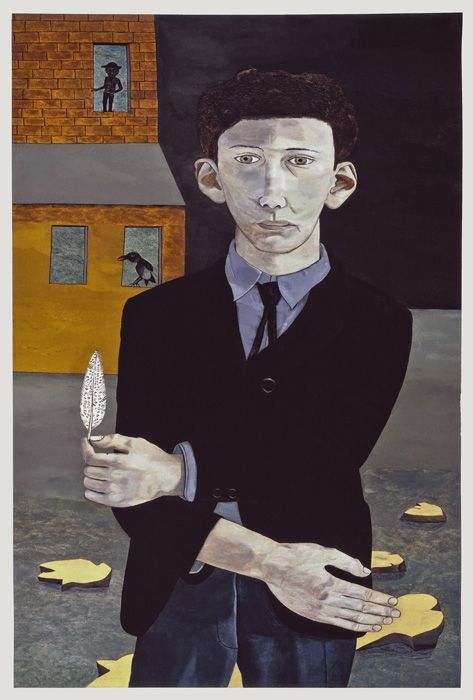

HOWGATE: We have 12 self-portraits in the exhibition, including two from the 1940s which could not be more different in style to the later ones. While the earlier ones including a surreal representation of Freud holding a feather, have a youthful arrogance, this is replaced later by more harsh assessments. In Self-Portrait (1981–2), he stands in profile, looking sideways at his reflection with an eagle-like stare. Reflection (Self Portrait) from 1985 is a particular introspective work: his gaze is elsewhere; his eyes appear to look inward. Freud himself said: “The way you paint yourself, you’ve got to try and paint yourself as another person,” and this philosophy is very much put into practice with these portraits.

THAWLEY: In your opinion, what are the most powerful works within the exhibition?

HOWGATE: The last wall in the exhibition has a group of three large portraits of David Dawson, Lucian Freud’s assistant, including Freud’s last, unfinished painting Portrait of the Hound. All three are tremendously powerful. I also have a favorite in The Brigadier, a masterful portrait of Andrew Parker Bowles, which has wonderful echoes of the National Portrait Gallery’s painting of Frederic Burnaby by Tissot. They were both in the same cavalry regiment.

THAWLEY: Are there perhaps some lesser-known gems?

HOWGATE: There are lots that are relatively unfamiliar, such as The Pregnant Girl (1960–61), which is a portrait of Bernadine Coverley, the mother of Bella and Esther Freud. And next to it we have a portrait of Bella Freud as a baby. The painting hung for years at Chatsworth House before her identity was known to its owners. More recently, the portrait of the restaurateur Sally Clarke from 2008 is being shown for the first time.

THAWLEY: What do you expect to be the impact on the art world of such a comprehensive exhibition? Is it revelation or celebration?

HOWGATE: While we cannot claim it is comprehensive, we have tried to secure for the exhibition the artist’s best portraits and we are very privileged that museums and private owners throughout the world have allowed us to display many iconic pictures from their collections in the exhibitions. To see all of them together should be an extraordinary experience. While Lucian Freud died last July, and he is not here to see the exhibition, he was very supportive of it. We had been working closely with him and his assistant David Dawson on the planning of it for over six years. So we very much see it as a celebration of the artist’s work rather than a memorial retrospective.